Science & Magic | 10

There’s a photograph I keep on my desk. It's from a family holiday in Great Yarmouth in the late ‘70s, taken on a Kodak instamatic camera that bled all the colours into a hazy, dreamlike wash. In it, I’m about seven, wearing bright red trunks with ferociously sunburnt shoulders, utterly absorbed in building an elaborate sandcastle. I remember the feeling with perfect clarity: a conviction, so absolute, that this magnificent, temporary thing would stand forever as some abstract architectural legacy. An hour later, the tide came in and, with a kind of casual indifference, erased it completely. I was, I’m told, inconsolable.

We seem to spend much of our lives building these sandcastles. We mistake the temporary for the permanent and are then shocked when the tide does what the tide always does again. The loss of a parent leaves a space so vast you can’t imagine it ever being filled, until one day you realise you’ve become the one now holding the safety net for the next generation. The acute, physical silence after a beloved pet dies feels like it will last forever, until, slowly, imperceptibly, the house learns to breathe again. A period when our mind and mood feels like a permanent weather system, until one morning, a sliver of blue appears on the horizon.

This isn't a cynical thought, it is, I think, the most profound source of hope we can have. The bad times are not a life sentence. And the good times are not assets to be hoarded, but moments to be inhabited, fully and completely, precisely because they are so fleeting. The beauty of the sandcastle was never in its permanence, but in the brief, glorious hour it stood against the sky.

The pieces in this newsletter are a celebration of that impermanence. They are snapshots, captured moments, temporary states of thinking and being.

In this edition, we have a ten-question expedition into the mind of writer and artist Valérie Bisson, revealing the books, films, and songs that have shaped her world. Jeff Young returns with a dispatch from a Patti Smith concert, where a single lyric becomes a portal back to his teenage bedroom in 1975. And we are thrilled to introduce our new fortnightly columnist, Pete Paphides, who continues The Paphides Principle with the stunning poetic melodies, symphonic and sprawling sounds of Andrea Laszlo De Simone.

Meanwhile, Nik Kavanagh offers a tribute to Rutherford Chang's We Buy White Albums project, celebrating the beauty of accumulated damage. Tom Roberts questions the very existence of a modern counterculture. Cal Sinjon takes us on a pilgrimage to a derelict holiday camp, searching for the ghosts of his own past, Joe Mckechnie shares a project thirty odd years in the making, and Rob Schofield charts a single life through a constellation of overlapping memories. We also have a special feature on our Manchester noise-niks Tigers & Flies, and works from Angie Woolf and Maya Chen.

These are not monuments, but dispatches from our ever-shifting present. We hope you find one that speaks to you.

Matt

Dix questions

à Valérie Bisson

De nationalité franco-suisse, Valérie Bisson vit et travaille entre Strasbourg et son minuscule chalet niché au cœur de la forêt vosgienne. Ses études de littérature pas encore achevées, elle commence à écrire pour quelques fanzines locaux et interviewe ses premiers groupes de rock avant de se spécialiser en danse contemporaine et d'intégrer la presse locale comme journaliste culturelle. Diplômée en édition et en communication, elle réalise plusieurs livres de commande et exerce sa plume en tant que conceptrice-rédactrice pour des artistes ou des organisations. Elle s’offre une parenthèse enchantée en apprenant les gestes techniques de la couture et en cumulant plusieurs expériences de costumière pour la scène et le cinéma, notamment pour la réalisatrice Sarah Leonor.

En toile de fond, la musique : des K7 pirates échangées à l’adolescence aux bacs à disques des capitales européennes en passant par douze années d’apprentissage du solfège et de technique vocale… Valérie reste toujours en quête du son de sa propre voix. En 2014, elle commence à écrire des textes plus personnels pour les Cahiers Européens de l’Imaginaire, le magazine NOVO et le site musical Section 26. Depuis 2020, elle est chargée de cours en licence Médias Langue Création à l’université de Strasbourg. En 2021, elle a perçu une aide du CNC comme consultante en documentation sur l’écriture d’un long métrage de Frank Beauvais. Enfin, un de ses textes est publié dans l’anthologie Écoutons nos pochettes aux éditions Densité, évènement qui sera suivi d’une lecture publique à la librairie parisienne Le Monte en L’air.

En 2024, elle conceptualise Textile, matières à texte, un manuel technico-poétique conçu et présenté à la Head-Genève, qu'elle réédite et relie à la main en vue d’une distribution à la Galerie de la graphiste Sarah Lang à Strasbourg. Mots entendus, écrits, chantés, brodés, Valérie Bisson continue à développer sa vision transdisciplinaire et sensible dans son projet Le Mot & le Geste, projet faisant du langage un lieu de résistance, de transformation, de liberté et d’auto-détermination.

—

Valérie Bisson lives a life of deliberate duality, dividing her time between the urban grids of Strasbourg and a tiny chalet nestled deep in the Vosges forest, a place that appears to be actively hiding from the 21st century. Her career has followed a similarly strange and wonderful path. She began by interviewing rock bands for fanzines, took a considered detour through contemporary dance journalism, and then, after mastering the practical arts of publishing, treated herself to what she calls ‘an enchanting interlude’ as a costume designer for stage and screen.

She approaches writing not as a single discipline, but as a transdisciplinary practice that can be woven, sewn, and embroidered. Music has always been the constant, humming presence in the background—from the pirated cassettes of her youth, exchanged like secret currency, to her current work for the esteemed music website Section 26. In recent years, she has received grants, published texts in journals and anthologies, lectured at the University of Strasbourg, and even conceptualised and hand-bound her own technical and poetic manual.

Through her ongoing project Le Mot & le Geste (The Word & the Gesture), she continues her quiet, determined work of making language a place of resistance, transformation and freedom. She claims she is still searching for the sound of her own voice, but to us, from this distance, it has never sounded clearer.

● Quel est votre son préféré qui n'est pas de la musique ?

Le bruissement des insectes en été. Quand je n’entendais pas les disques de mon père, de mon frère ou les chansons populaires de ma mère, je passais beaucoup de temps dans la nature aux aguets des moindres signes de vie. Et la vie grouille dans le règne végétal : bourdonnement d’abeilles, déplacements de feuilles, si on prête l’oreille on peut même entendre les fourmis.

● Quel album donneriez-vous aujourd'hui à un jeune de 18 ans en lui demandant de l'écouter en entier ?

The Velvet Underground & Nico. Il y a une histoire de la musique rock contemporaine dans cet album riche de différentes atmosphères ; il syncrétise à la fois le passé et le futur. Il me parait essentiel aussi à la compréhension de la palette d’émotions qui peuvent constituer un être humain.

● Quel est le premier disque que vous avez acheté avec votre propre argent ?

The Cure, Seventeen Seconds. Inexorablement, il fait partie de mes brumes adolescentes, de ma mélancolie constitutive, de ma volonté de m’ouvrir à d’autres paysages.

● Quel album vous a aidé à traverser une période difficile ?

Neneh Cherry, Homebrew. Les arts textiles, la maternité, Neneh et ses cheveux afro, son père, tout ce qui fait une femme depuis que le monde est monde doublé d’une parole et de sons bien trempés, sans compromis. Ce deuxième album de Neneh Cherry la fait entrer dans une nouvelle dimension et affirmer la puissance de la douceur, c’est autre chose que du féminisme, c’est l’affirmation forte et tranquille de la reconnaissance d’une autre voix. Cet album incarne tout ça à mes yeux et je l’ai beaucoup écouté entre 25 et 30 ans.

● Quelle chanson devrait être le nouvel hymne national ?

Björk, 'Declare Independence'. Je crois que l’énergie brute et les paroles de ce morceau illustrent parfaitement ce qu’on peut mettre dans la préservation de son libre arbitre, de la résistance à l’oppression, de la puissance de l’auto-détermination.

● Qui est la personne qui vous donne les meilleurs conseils musicaux aujourd'hui ?

Thomas Schwœrer et toute la bande de Section 26. En 2020, Thomas m’a proposé de rejoindre l’équipe pour écrire quelques articles. J’ai dû remettre en marche une curiosité musicale un peu perdue de vue. Si depuis je contribue au site de manière sporadique, je lis en revanche tous les articles de ce « prescripteur pointilleux, passionné et indépendant de l’entre-soi pop moderne depuis 1991 ».

● Quelle chanson est indissolublement liée au souvenir d'un voyage particulier, au point que l'entendre vous ramène immédiatement à ce moment et à cet endroit ?

Kimya Dawson, 'Remember That I Love You'. Une longue traversée de l’Allemagne en décembre 2008, direction Prague pour y fêter la nouvelle année chez des amis, une longue route avec des températures qui chutent à -20 degrés Celsius, deux enfants en bas âge emmitouflés à l’arrière de la voiture et cet album en boucle pour se donner du cœur et de la joie pour avancer.

● Quelle est votre chanson préférée pour vous procurer une joie pure, simple, qui vous donne envie de monter le son et de danser ?

Henri Mancini, 'Lujon'. Le corps tout en sens et en mouvements, suave, sensuel, ondulant, souple et libre, la promesse de l’amour, le désir à l’état pur ; luxe, calme et volupté.

● Les paroles de quel auteur-compositeur pourraient figurer dans un recueil de poèmes sur votre étagère ?

Trish Keenan. Tout fut singulier chez elle, son destin, sa voix, son physique et ses écrits auxquels je suis très sensible. Vaguement ésotériques mais surtout extrêmement poétiques.

● Si vous deviez broder une seule phrase sur une couverture que vous transmettriez de génération en génération, laquelle choisiriez-vous ?

"My morning sun is a drug that brings me near to the childhood i’ve lost" (New Order, 'True Faith'). D’ailleurs, je l’ai brodée au fil Rouge du Rhin sur ma veste de travailleuse bleu indigo.

—

● What is your favourite sound that isn't music?

The buzzing of insects in summer. When I wasn't listening to my father's or brother's records or my mother's more popular songs, I spent a lot of time in nature, listening for the slightest signs of life. And life abounds in the plant kingdom: the buzzing of bees, the rustling of leaves... if you listen carefully, you can even hear the ants.

● Which album would you give to an 18-year-old today and ask them to listen to it in its entirety?

The Velvet Underground & Nico. This album, rich in different atmospheres, tells the story of contemporary rock music; it syncretises both the past and the future. I also think it's essential for understanding the range of emotions that can make up a human being.

● What was the first record you bought with your own money?

The Cure, Seventeen Seconds. It’s part of my teenage fog, my natural melancholy and my desire to open myself up to other landscapes.

● Which album helped you through a difficult period?

Neneh Cherry, Homebrew. Textile arts, motherhood, Neneh and her afro hair, her father, everything that makes a woman since the world began, coupled with strong, uncompromising words and sounds. This second album by Neneh Cherry takes her into a new dimension and affirms the power of gentleness. It's more than feminism, it's the strong and quiet affirmation of the recognition of another voice. This album embodies all of that for me, and I listened to it a lot between the ages of 25 and 30.

● Which song should be the new national anthem?

Björk, 'Declare Independence'. I think the raw energy and lyrics of this song perfectly illustrate what it means to preserve one's free will, resist oppression and embrace the power of self-determination.

● Who gives you the best music advice today?

Thomas Schwœrer and the whole gang at Section 26. In 2020, Thomas asked me to join the team to write a few articles. I had to rekindle the musical curiosity that I had somewhat lost sight of. Although I only contribute to the site sporadically, I read all the articles by this ‘discerning, passionate and independent critic of modern pop culture since 1991’.

● Which song is so inextricably linked to the memory of a particular trip that hearing it immediately takes you back to that moment and place?

Kimya Dawson, ‘Remember That I Love You'. A long journey across Germany in December 2008, heading to Prague to celebrate New Year's Eve with friends, a long road with temperatures dropping to -20 degrees Celsius, two young children wrapped up warm in the back of the car and this album on repeat to give us the heart and joy to keep going.

● What is your favourite song to give you pure, simple joy, making you want to turn up the volume and dance?

Henry Mancini, 'Lujon'. The body full of meaning and movement, smooth, sensual, undulating, supple and free, the promise of love, desire in its purest form; luxury, calm and voluptuousness.

● Which songwriter's lyrics could be included in a collection of poems on your bookshelf?

Trish Keenan. Everything about her was unique: her destiny, her voice, her appearance and her writings, which I find very moving. Vaguely esoteric but above all extremely poetic.

● If you had to embroider a single sentence on a blanket that you would pass down from generation to generation, which one would you choose?

"My morning sun is a drug that brings me near to the childhood I've lost" (New Order, 'True Faith'). In fact, I embroidered it with Red Rhine thread on my indigo blue work jacket.

Magnetic North

by Jeff Young

10 : Birdland

It’s the way the singer murmurs the words His father died... that makes me cry, unexpectedly, overcome by an overwhelming feeling that I am dissolving into a reverie of memory and loss. Patti Smith is onstage at the London Palladium celebrating the 50th anniversary of ‘Horses’, her arms outstretched, her voice childlike, sorrowful and lonely as she half sings, half sighs the opening words of ‘Birdland’: All the long black funeral cars left the scene, And the boy was just standing there alone...It’s like a prayer or a mournful lullaby and it’s achingly beautiful and sad.

Death has felt close all day so perhaps it’s no surprise that I’m in tears. It’s the 13th of October and today would have been my mum’s 95th birthday. Heartbroken over the recent death of my beloved cat, I’m just about keeping it together but to add death to death it’s also two years since my dad died. And so, when Patti utters those three words, “His father died...” not only am I reduced to tears, but I’m also suddenly transported to my bedroom in 1975 with a brand new copy - bought in Beaver Radio on Whitechapel - of ’Horses’ on the record deck.

My parents are downstairs – mum in the kitchen getting the tea ready, dad in the garage messing around with whatever piece of furniture he’s just bought in the auction – and in my room the record is spinning, the volume is getting louder, and the room is transformed. It’s no longer a tiny bedroom in a suburban semidetached, it’s some kind of emotional space station or dancehall full of dreams. This is what great songs do to us, they take us into dreamland, they turn bedrooms into fairgrounds and cities, they grant us the gift of time travel, and they give us permission – if we need it - to have a broken heart.

In the Palladium, in the song’s bittersweet dream space, here comes the swirling past. Here is Billy Fury, and here’s and a wounded blackbird in a shoebox; Danger Man is on the telly and apple crumble is baking in the oven; Here’s an Airfix Spitfire in flames, Spot the Ball, Harvey and the Moonglows, The Jetsons, Bob Latchford, Bazooka Joe bubblegum. Here’s a Ray Bradbury paperback, dad’s sellotaped glasses. Here’s a Doctor Strange comic and mum’s marigold gloves...

For a fleeting moment I am back there, in the house in this photo. The ordinary is beautiful. Sadness feels like the surest sign of love. And I am listening to records in my bedroom and my parents are alive.

— Jeff Young, 14 October 2025

—

Jeff Young, who currently holds the prestigious TLS Ackerley Prize, treats the past as a room he can re-enter at will. His dispatch this week is a field report from one such journey, a time-slip initiated by three words sung by Patti Smith that transported him from the London Palladium directly back to his teenage bedroom in 1975. Jeff believes that songs are functioning time machines, capable of collapsing fifty years into a single, aching moment. And he’s right.

The Paphides Principle

Pete Paphides is the cultural guide you learn to trust implicitly. In a world of infinite choice and algorithmic noise, he possesses a rare ability to find you the one new song that matters.

His fortnightly dispatch for us, The Paphides Principle, serves as the quiet correction to the churn. It is an ongoing argument for the enduring power of a perfectly crafted song. Enjoy his latest selection.

Andrea Laszlo De Simone: La Notte

This time last week, I’d never heard of Andrea Laszlo De Simone. Then on Monday, my pal Andy messaged me with a link to a song called ‘Il Nostro Giorni’, in which Andy correctly pointed out that: (a) “this came out a couple of years ago (but could have been released anytime in the last 50 years)”; and (b) that “it’s stunning.” As usual, Andy was right. On his rounds as a postman in St Albans, he keeps his earphones in – and I’m trying to imagine the emotional dissonance of delivering parcels to Verulamiam Museum and Waggy Trails Dog Boarding and Day Care and while hearing De Simone sing a lyric about lives transformed by an unspecific perhaps irrecoverable seismic event: “Cold wind blows over our days,” he intones in Italian, “And behind the doors/Closets of dreams/Wait for our life/To return.” As we pull back to apprehend the scale of this this baroque pop requiem, I remember Van Dyke Parks telling me about the first time he heard Joanna Newsom’s demos for Ys: “In my mind were the images of the bards, the troubadours, the poets. And the very druid marrow of my bones started shout at me, ‘You should serve this person. This is an anomaly to a very dull event called popular music.’”

The next morning I went online and learned as much as I could about Andrea Laszlo de Simone. Born in Turin to to the sort of parents who name you after a Hungarian film director (László Kovács). Originally the drummer in a band called Nadár Solo. His work over the past decade or so has encompassed classical and pop elements. I ordered everything that’s available, including his new album Una Lunghissima Ombra (A Very Lengthy Shadow) which is out on the day you’re reading this. As I write though, I’ve only heard two songs from it, so my selection for Science & Magic #10 is ‘La Notte’: a plaintive paean to lost innocence that dispenses its sweet ache upon you like an autumn mist. “The night,” he sings (again, in Italian), “Hides thieves and hides a flower too.” The more I hear, the more otherworldly this man’s gifts seem. His audible forbears sound (to me) mostly French: Gainsbourg, Tellier, Polnareff, Dutronc – to which you can maybe also add the lyrical and compositional elan of his compatriot Paolo Conte. I’m just at the beginning of a long, lovely arc of discovery here. Care to join me?

—Pete Paphides, 16 October 2025

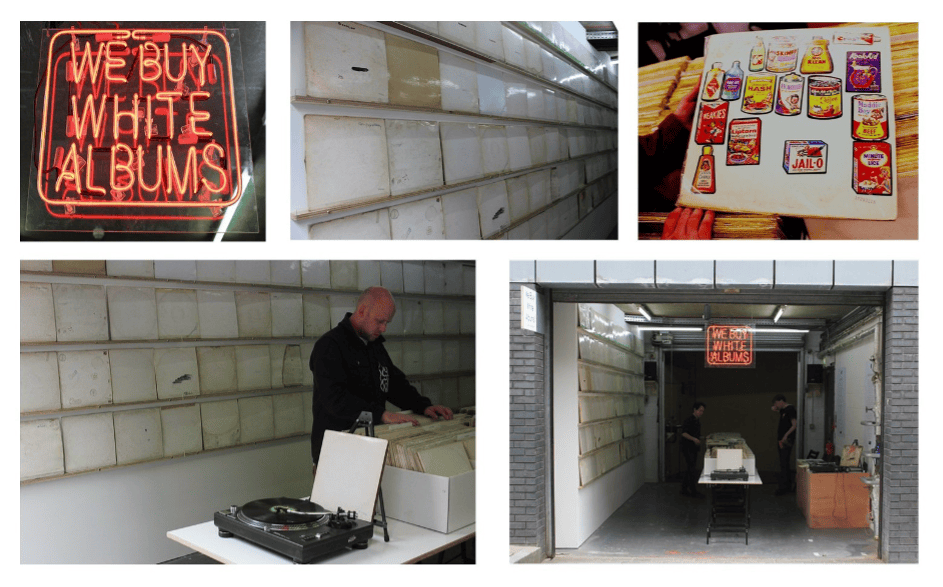

He Bought White Albums

by Nik Kavanagh

I love vinyl, I love collecting, I love art, and I love The Beatles. So, when I saw a poster back in 2014 announcing an exhibit called ‘We Buy White Albums’ was coming to Liverpool my cup runneth over.

For a little bit of context, ‘The White Album’ is the ninth studio LP by The Beatles which came out in November 1968. The record’s official title is The Beatles but it is more commonly known as ‘The White Album’ in reference to the record’s cover. The sleeve has the band's name embossed on a plain white background and original copies were also stamped with a serial number unique to each copy. The sleeve was designed by Richard Hamilton who initially suggested tainting the virginal cover with a coffee mug ring but was told this was “too flippant”.

The ‘We Buy White Albums’ installation consists of a collection of multiple used vinyl copies of “The White Album” presented in a minimalist, curated environment that mimics a second-hand record shop. The man behind the project was conceptual artist Rutherford Chang (which is a belter of a name), and he only collected White Albums, and he only collected White Albums that were stamped with serial numbers. At his gallery shows, he displayed these records on the walls and in crates in numerical order. Obsessive? Yes, but it is this obsession that I find really fascinating and interesting.

The collection highlights the unique history and imperfections of each individual record, emphasizing how each record has matured over time. The many copies of the record sleeve, which were basically blank canvases, document the transformation of the originally identical albums into unique artifacts. Each copy accumulating its own unique history of wear, dirt, and markings over the years. Some copies were faded, some were marked, some were ripped, some were repaired, some were mildewed, some had other people's drawings, illustrations or their names written on them, as well as photos, stickers and all manner of other embellishments.

During the installation visitors could experience a mixed-media composition of all four sides of the album played simultaneously as a single mix. Rutherford would also have two turntables at the installations and would constantly be playing ‘The White Album’, he would make a digital recording of each copy in the collection. Eventually he got a digital artist to layer 100 of these digital recordings over each other. As an auditory experience it is a cacophonous, yet intruiging composition with moments of real beauty. It starts out with ‘Back in the USSR’, and you hear a sort of echo of all 100 copies being played together. Some are scratched, some are just really worn, some have pops and crackles and they’re all being played back at once.

Eventually, as the record continues, you realise they become out of sync, and you hear a wash of echo. Is it the imperfections on the vinyl that puts them out of alignment? Or is it the battle scars they’ve picked up along the years? Is it the speeds of the different turntables, the different pressings or maybe the mastering that has turned this into industrial noise, who knows? This is not an easy listen.

This ‘collage’ mix was pressed to vinyl in a limited run of 1000 copies which were sold at the exhibit and it came housed in a sleeve which consisted of a composite of 100 of Rutheford’s favourite covers from the collection collated into one single sleeve. Also included was a poster of the 100 individual sleeves that make up the composite. You best believe I bought myself a copy!

What I found really appealing about the whole project was that, as well being a brilliant piece of visual and sonic art, ‘We Buy White Albums’ is also a celebration of collecting. The project explores themes of collection, personal archives, and the physical presence of objects in the digital age. I’m not sure what will happen to the collection now that Rutherford is no longer with us but if you ever get a chance to experience it don’t let it pass you by.

Dedicated to Rutherford Chang 1979 – 2025.

—

Nicholas ‘Nik’ Kavanagh is a musician who believes that an object’s history is more interesting than the object itself. He approaches his record collection as a library of music and as a museum of beautiful, accumulating damage. He is drawn to the pops, the crackles, the coffee stains, and the handwritten dedications - the unique battle scars that transform a mass-produced item into a singular artefact. He is currently composing a symphony using only the sounds a record makes when it is not playing music. This project, ‘The Sound of a Life Being Lived,’ is a catalogue of the pops, crackles and silences that document an album's journey through time. He believes these flaws are a form of secret, percussive language of fantastic errors. For Nik, perfection is a fiction, the real story is found in the beautiful, chaotic topography from the collateral damage of life.

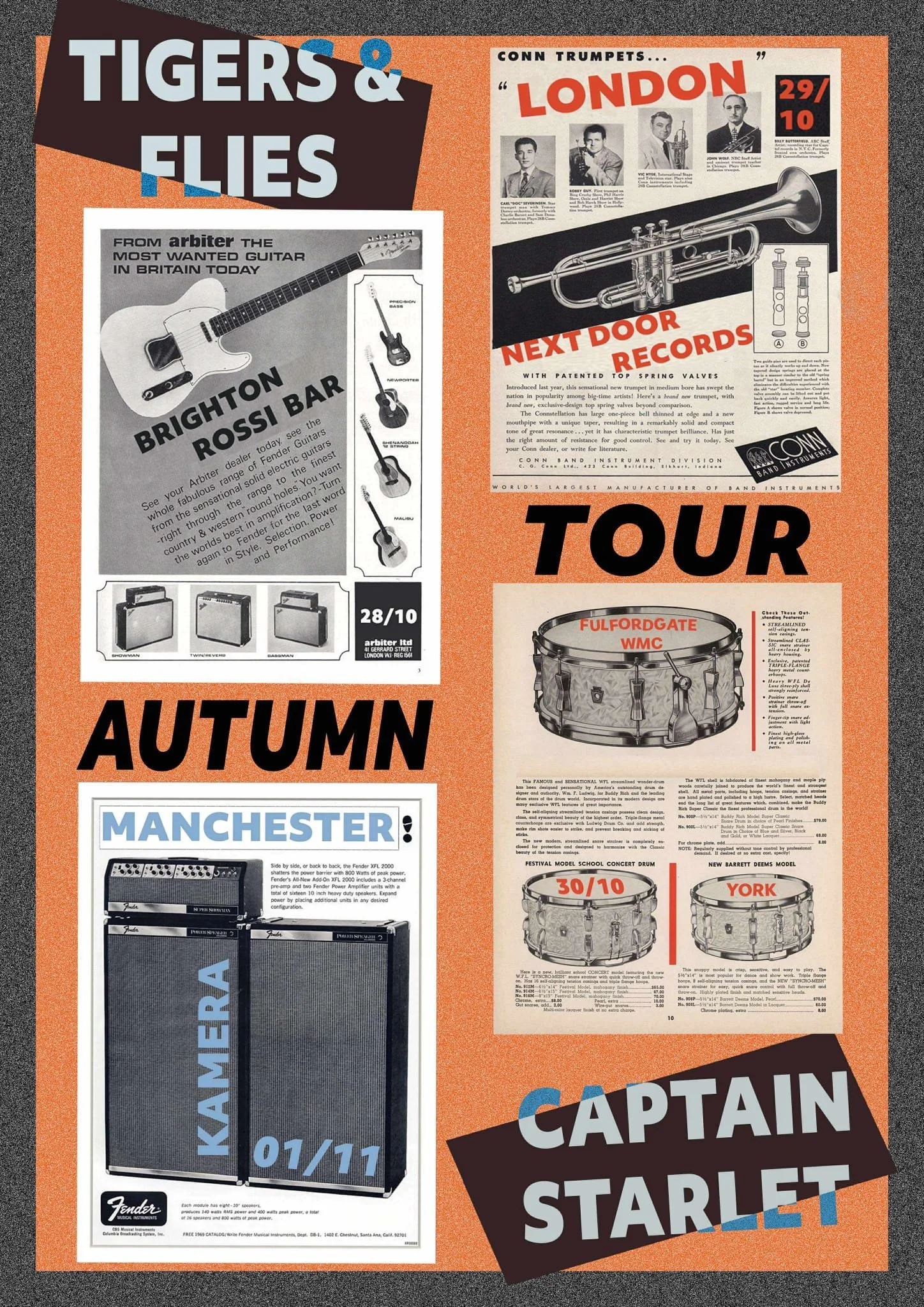

The Circuits Are Live, The Vinyl Is Pressed, The Van Is Loaded.

You’re watching five people load gear into a Transit van that appears to be held together by gaffer tape and sheer, bloody-minded optimism. Manchester rain hammers the roof like applause from a god who appreciates chaos, if not necessarily music.

This is Tigers & Flies. This is what happens when the quiet, persistent need to make your own noise escalates into something resembling a kind of religious conviction.

I've seen them load in. Arthur's amp looks like it weighs more than his student loan. The rhythm section, Arvin and Eddie, move with the careful precision of people defusing a bomb, because in a way, they are. Every one of their gigs is a controlled explosion, a planned demolition of the silence that threatens to creep in at the edges of our modern lives.

The numbers are, as always, beautifully impractical. One hundred copies of vinyl. Eight tracks. Five humans who met in lecture halls and, at some point, collectively decided they would rather fail at music than succeed at anything else.

Their new record, Expanded Play, is out later this month. Not because the world is crying out for another record, but because these songs have earned the right to exist outside the sweat-soaked rooms where they were born. You’ll have heard about their show in London where the power died mid-set, and the entire audience, unprompted, just kept singing the words back to the band in the dark. That's a data point that streaming metrics will never be able to measure. That's the whole point.

The tour starts in rooms that are slightly too small for the sound they make, and to audiences who understand that live music is a form of communion.

Brighton, Rossi Bar, October 28th

London, Next Door Records, October 29th

York, Fulfordgate WMC, October 30th

Manchester, Kamera, November 1st

When Tigers & Flies play, something happens. It isn't magic - that word's too clean, too polite. It's more like electricity finding ground through a roomful of human bodies. Arthur's voice cuts through the noise with surgical precision. The horns, from Risha and Matteo, are less an accompaniment and more a statement of intent. The rhythm section bends time until it threatens to snap.

This is five people who understand that making this kind of music in 2025 is a quiet act of resistance. Resistance against algorithms, against atomisation, against the slow, creeping death of the shared experience.

The vinyl is limited because everything meaningful should be. The shows will sell out, or they won't. But they will happen. Because it isn't music for consumers, it's for their accomplices. It's an invitation for anyone who's ever felt the world closing in and decided the only sane response was to make a beautiful, defiant noise.

The van is loaded. The amps are buzzing. We hope you'll be there.

SubjectTo Change

by Cal Sinjon

It wasn’t a surprise to find the door unlocked- there’d long been a sneaking suspicion that all the locks on every door could be opened with the same key, but in this case, I didn’t need one anyway! Inside, there were 2 single beds, still made, a small wooden dining chair and 2 single wardrobes, each with a customary dropped lopsided door, a wash basin, a mirror and…nothing else.

Sitting on the bed, glad of the respite from the howling January wind and rain, I noticed there was a small colour programme sticking out from under the opposite bed. I was amazed to find it was still very much intact and readable, but just as I was about to leaf through the contents…SHIIIITT!

A small white van had pulled up a couple of doors down….and, battling against the North Sea gale, 2 men in security uniforms emerged with an Alsatian dog, which seemed extremely keen to sink its teeth into something, or someone.

The dog handler was struggling to hold back the ferocious animal and was being dragged left, right and backwards whilst he effed and jeffed some indecipherable Yorkshire brogue profanities.

I stood behind the solid door out of view, but I could now feel that my heart was beating in a way that made me believe it was as audible as a military band’s bass drum. Was I really trespassing? What crime was I committing? Why have I suddenly turned into a pathetic, dry mouthed wreck. They started pushing open the other doors until they got to mine. In a deluded attempt to confront the situation and offer an explanation, I pulled open the door at exactly the same moment as one the Hale and Pace lookalikes was about push it through. This very act startled all concerned.

There was a collective loud exclamation of… “what the fuck!!” instantly followed by a cacophony of manic shouts – ‘get back!’ ‘Down!’ ‘Come ‘ere!’ ‘Jesus!’ ‘For Fuck’s’ sake!!’ ‘Steady tha’sen’

The dog was going ballistic; hoods were being blown off and we were all shouting at once.

I don’t know why, but I put my arms up like some sort of surrendering soldier. ‘Don’t shoot’ I felt myself exclaiming. ‘Don’t shoot’!? What am I thinking?

There was a short standoff. No one knew really what to do next. These two fellas had probably been doing a Wordsearch or listening to afternoon sport in the van. The dog had probably been intermittently dozing, occasionally pricking up its ears to the whistling gusts through a gap in the back of the van doors.

The conversation went something like this…

(Yorkshire) Man 1: ‘What the fuck are thou’ doing’

(Yorkshire) Man 2: (to the barking dog) ‘Shut it! Shut………… it! Put wood in t’hole!’

Me: (Suddenly 3 octaves higher) ‘Just looking around, like’

Man 1: ‘You’re on the rob aren’t cha, what you nickin’?’

Me: …. ‘Robbin’? …Nothing, I’ve come up to look around, that’s all.’

Man 2: ‘Are you on day release? Look around? Look at what?’

Me: ‘The site, this place, I came here all the time on me holidays until I was about fourteen’

Man 2: ‘Well It’s closed’ …(silence)

Me: ‘Yeah, I know that, that’s why I’ve come here’

Man1: ‘He was about to rip your head off’ (referring to the dog), ‘are you stupid, can’t you read?’

Man 2: ‘where did you get in from?’

Me: ‘Down there, from the beach path, there’s a hole in the fence, so I just sort of let myself in.’

Man 1: ‘Check it out, George. There could be others ‘

Me: ‘Honestly, I’m here on my own. I travelled up this morning.’

Man 2: ‘Are you Irish?…..’

Me: (Indignant) ‘No…Liverpool’

Man 1: ‘Same thing’

It’s only been eight years since my last visit but in that time, I’d gone from a boy to a young man. In that time, there’d been the loss of childhood, the loss of a parent, the loss of familiarity. Time as a child is endless. Time as an adult doesn’t exist. The passage of time. I’d gone from a spotty virgin to an ale swilling, curry beef, half chips half rice Friday night youth in the blink of an adult’s eye. The lads will be out on the town and here’s me on a train, wet and freezing on a journey to nowhere. What was I expecting to find, expecting to see? What was the pull, the draw?

The term Urban Explorer hadn’t been invented and of course, I knew the place was long closed. I knew in January it would look bleak, but the mirage of memory, happiness and pain was all consuming and in full technicolour. It was keeping me awake. I simply had to make this pilgrimage. Standing at Lime Street, I felt invisible, like a sleepwalker in stripey pyjamas, dressing gown, with the belt trailing in the puddles behind. Slipper’s soaking. Invisible to the world.

Apart from asking for the train ticket, I’d not spoken to a soul. Three hours later, I arrived at the beach. It’s flat and hard. Pristine. North Sea waves crashing. That white/grey light and roar of the sea. Invigorating.

I can see my Land of Oz almost two miles ahead along the coast, teetering on the clay cliffs. Coastal erosion is winning the race against time. The sea spray only adds to the mystique. And so, I walk. Intermittently, I look behind, seeing my starting point vanishing, my footsteps in the sand becoming smaller as the warmth of the intervening years start to evaporate into the mist, as if I’ve gone through into another dimension.

The sound. Halfway up the beach path, the sound starts to fade. The roar of the sea seems to relent like distant thunder and fades into eerie calm, punctuated only by wild gusts of wind, whistling through the wild vegetation.

I see the perimeter fence. ‘Keep out’ …’Trespassers Will Be Prosecuted’ …….and then the first glimpse……the first tangible inanimate object to make me stock still. The beach chairlift station and the pylons, increasing in height as they fade into the drizzle. It’s here. I’m here. My Holy Grail. I pause at the hole in the mesh fence, hidden within the flora but with a deep breath, I’m through and in. It’s hardly a Neil Armstrong giant leap for Mankind but to me, I’ve landed on another planet. Sacred ground.

I make my way to the chairlift station. All mechanisms are intact. An assortment of coloured cabins still hanging. The red concrete floor, which bore the footsteps of Oxfords, Bata, Stead and Simpson, Dr Martens. The huge horizontal wheel looms from the roof. Of course, there’s a few slates missing from the roof, but the building stands rigid and proud, still connected by a cable to the other end half a mile away. I’m standing alone near to the entrance, where thousands had stood previously, queuing excitedly, for that aerial view of the camp, of the coast and that silence of midair. The drizzle was turning to proper rain. The knee-high grass leans at 45 degrees in the wind.

I make my way up the slope towards the chalets. Several rows are still standing in straight lines laid out before me. Is this reckless vandalism, storm damage or the beginning of a site clearance? The sight before me looked like the aftermath of a bomb attack on a film set. And so, I arrive at my chosen door. I enter. I sit on the bed. Can this be the same place? It’s tiny, it’s cold, it’s basic. It was your resting place after a full day of breathless activity. A place to ease those aching calf muscles against the cool of starched white sheets.

These walls had reverberated for over 40 years to the themes of Jazz and Swing, Rock and Roll, Glam Rock and Punk. They’d bore witness to talk of hope and resilience, rationing, the Coronation and ‘you’ve never had it so good’! These chalets had been a weeklong home to the pioneers of youth culture, miniskirts, the Pill, LSD, while newspapers in the waste bin would’ve headlined ‘The Great Train Robbery’, ‘England Win the World Cup and ‘Man lands on the Moon’. The mirror above the sink basin reflecting faces washed with Lifebuoy and Lux. Faces lathered and shaved in coal tar soap. Four Walls. An enclosed space of escape from ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’, the Winter of Discontent and the impending wastelands of Margaret Thatcher’s dystopian Britain. This room, this space, these fields of hope, crumbling and dying in the gales of a winter’s day.

But wait, here’s that white van…

There was to be no whirring or rumble of the chairlifts over the pylons, the futter of flags across the sports field in the North Sea breeze or the smell of egg-burgers and fried onions from the Stadium Café Bar. No sound from the elegance of the Viennese Ballroom.

There was to be no clack of billiard balls or screams from the funfair. No sudden waltzy vibrato organ chimes as a door opens and closes, or the sound of gaiety and laughter. No daytime florescent lighting against a thunderous North Yorkshire summer sky. Doors were missing, windows were smashed, graffiti daubed, and ragged curtains fluttered. Rooves were caving in.

My short-lived sojourn into my Xanadu was abruptly halted by the dream busters. Reality was here. The reality that I’m in the back of a van, on a soaking Saturday afternoon in January, One hundred and fifty miles from home, with a wet raging dog, being driven to the site security hut by Beavis and Butthead, to be processed and thrown onto the A165.

The journey home was filled with confusion and slight embarrassment. What was I looking for? Was it a feeling? How could or how can retracing steps ever be the same? You saw it through different eyes. The memory will shade or colour the scene to match your picture but it’s just as likely to leave you with a heavy heart.

Double the grief. Double the confusion.

The journey home becomes a burden of overthinking and being unable to find the answers to questions you didn’t have at the time you were last here. Was it all good? What backdrop came with us? I was the child, unburdened. The adults had lived through time and the pinball machine battering that life’s bruises leave. Were they as happy as I was?

After an hour of waiting for the train home, the sudden overwhelming sorrowful feelings at the sacrifices made by others, to give me what I’d wanted, over their own needs for a well-earned break left an internal bleeding. The sudden adult realisation that the place was undoubtedly already being viewed down the long noses of more comfortable neighbours, as a symbol of decline. Second class. A dirty word. Like being splashed at a bus stop and pitied by those passing in their liberation of a new motor car but they had no idea.

Whist they were sitting at their cheap white plastic tables and chairs, in their Pringle Tee shirts, drinking watered down piss in 35-degree heat, watching 5th rate cabaret in some concrete tower block in Costa Del Elsbells, I was having jam and cream waffles, playing snooker and watching Top of the pops in a smoke-filled darkened room, with faded and worn velvet seats, full of punks, mods and new romantics.

But whilst I may have been shouting from the rooftops about going to my mecca, I now realise there was most certainly a collective ignorant snigger from those in my neighbourhood. My Utopian playground was a symbol of District 12. A relic. A symbol of limited income. A symbol of limited horizons and mobility.

The journey had not served its purpose. It’d opened a can of worms. Memory, regret, anger. The place was after all, derelict and overgrown. The heart had stopped beating. There were no ghosts. ‘They’, weren’t there. ‘They’, had gone.

My foray into the mists of time was fruitless but it had awakened me. Awakened me to the realisation that whilst the remains of buildings and location can aid as a marker of place, the passage and ravages of time affect the memory. Snapshots. Single moments, seconds, colourised and replayed as if that moment had lasted much longer. It was but a fleeting glance. The smell of a donut and you’re there. The cry of a seagull and you’re there. A song on the radio and you’re there. But you’re alone. It’s just you and that damned memory. Memory hoarding. When you look up ‘hoarding’ as a reference you see it’s a kind of temporary fence put up around a structure being built or protecting something fragile, but another search will have it defined as ‘to accumulate for preservation, future use’, like a squirrel gathers nuts for the winter.

You keep a newspaper, and the articles can be debated but the contents of that article will remain constant. A photograph can capture an image, and that image will remain constant as long as the material upon which it’s printed holds up, but memories do not obey the same properties. A distorted belief that memories can be treated the same way as inanimate objects. Memories change.

The memory that recalls. The memory that lingers, but if revisited, if peered through from behind the curtain, may be subject to change.

—

Cal Sinjon is a part-time writer and full-time observer, a veteran of inner-city Liverpool who still navigates the city with the wide-eyed curiosity of a 1970s child who has just discovered that the world is significantly weirder than originally advertised. Having matriculated from the school of hard knocks directly into Thatcher's brutalist utopia, he now spends his days working and his nights dreaming, treating every human interaction as an unsolicited opportunity. He puts his faith in two things: Karma, and the revolutionary power of a well-chosen post-punk B-side. He has written, and is negotiating his publisher’s contractual small print, a secret history of Liverpool told entirely through the medium of forgotten playground songs

Drifting…

with Joe Mckechnie

Joe Mckechnie’s musical journey is a map of Liverpool's hidden histories, a web of connections that stretches from post-punk to the present day. His story begins in groups like The Passage and The Balcony - where he first played alongside last week's guest, Steve Powell - before he went on to found the Thomas Pynchon-inspired Benny Profane. He is a musician who has always operated in the city's interesting margins, treating every chance encounter as a potential future collaboration.

The piece he shares here today is a perfect example of that philosophy in action. It's a story that begins with a cancelled gig in post-Velvet Revolution Prague in 1990, lies dormant for three decades, and is then unexpectedly resurrected during a global lockdown by the chance discovery of an old gig poster. It’s a testament to the threads that connect us over time and space, music born from friendships that refuse to be forgotten.

Drifting… is a series of these correspondences. Shared ideas built aided by the quiet, persistent magic of the internet. We are thrilled to present the first of these dispatches, a collaboration with Swiss singer Pascale Martini that closes a thirty-year circle.

May 1990 :

Our group, Benny Profane, is in Prague, we’ll play three gigs as part of a European tour that also takes in Austria and East/West Germany.

The Prague gigs are to promote the Velvet Revolution/We Vote campaign, to get out the vote in the forthcoming post Communist elections.

The main event, a Festival on Střelecký Island on the River Vltava, doesn’t happen - rain stops play.

We do play two outdoor/daytime gigs, one on the Old City Square, and a short notice gig at the out of town Velká Chuchle Racecourse.

Gig three is in the Prague Rock Cafe.

We’ve become friendly and played gigs with some of the other groups who’ve travelled to Czechoslovakia for the Festival. Pascale Martini, the singer with the Swiss group Blu Dolphin, mentions that she’d like to visit Liverpool on a forthcoming trip to the UK. Back in Liverpool for a week, Pascale and I have a go at writing some songs, but none of them take.

May 2020 :

Lockdown. Covid-19 is going to be a nice little earner for some.

All watched over by a Tory Government disgrace.

I’m at home looking through a stack of old gig posters when I spot the poster for the cancelled Prague ‘We Vote’ gig from 30 years before.

Was it 30 years to the day? Let’s say it was, what are the chances!

As I’m wondering what ever became of Pascale I remind myself, as I sometimes have to, that the internet exists.

One search later we’re back in touch and from her home in Zurich Pascale is asking if I’m still doing music?

I send her a couple of tracks I’m currently working on, one is an instrumental I’m calling ‘Folk Song of the Twilight Zone’.

To my surprise Pascale sends the track back with added singing, now you're talking.

After a bit of back and forth online we end up with 'Song of the Twilight Zone', the first in a series of songs they’re calling ‘Drifting ft…’

As time goes on I’ve been able to call on various authors and singers to guest on Drifting ft… tracks.

As I like to say ‘I’ve got to be Drifting’.

— Joe Mckechnie, 16 October 2025

A Life

by Rob Schofield

The queue for the late show at the Liverpool Empire begins on Lime Street and angles east up Lord Nelson Street. A young couple – not much more than a boy and a girl – are in a section packed together like a Roman Legion, heavy overcoats and mackintoshes offering scant defence against the wind and drizzle sweeping up from the river. They are on a first date, but have known each other for some time and are holding hands. Some people curse the weather and others are excited about the show, while he is talking about Egypt. In two minutes he will be telling tales from the butcher’s shop. He won’t stop talking. He will never stop talking and he will be known for it, in a good way. One of his sons – they will have five children – will be the same and there will be other more distant relatives who never stop talking. This gene runs strong in one tributary of a vibrant and meandering family that will come together for the next seven decades at baptisms, birthdays, weddings, anniversaries and funerals.

He puts an arm around her when he hears her teeth chatter. He tells her about the house where he lived with his mother and grandparents until he was seven. It was a house of love and friendship, the kind where the front door is never used and the back door never locked. He’ll return to this house, which stays in the family, over and over until he no longer has the strength to do so. He moves on to something else. Perhaps he talks about the show. Neither of them will forget who is top of the bill that night, but sixty eight years later, when a man who had been training for the priesthood delivers a eulogy for the young man queuing outside the Empire, only two or three of the mourners will look up when they hear the singer’s name.

One of those mourners will be his cousin. She also grew up and still lives in the house to which our young man returns so often. As they drive to the wake she will tell her son about how the young man, married by now, had had a spare ticket for another show because the young woman was too far along with their first child to stand in yet another queue outside the Empire. This was the cousin’s first concert and she will remember that top of the bill was Lonnie Donegan and at the bottom, wearing the luminous socks favoured by the Teddy Boys (although he himself was never one) was Des O’Connor. She loved Lonnie Donegan, but Des divided opinion. The son, eyes on the road as they snake around Lancashire in search of a sports and social club where his brother once played cricket, will smile because he knows about Lonnie Donegan’s place in the history of British rock and roll. He had smiled earlier, was moved to tears in fact, when he heard that he had been born in the same hospital as the young man, albeit thirty six years later. This son grew up in the same house, to which he returns over and over and where he hears stories about brothers and cousins and mums and dads and aunties and uncles and as he listens he fears that one day he will wish he had written some of them down.

The cousin tells her son how the young man loved music. His children did too, but who didn’t in those days? The young man in the queue, who will work three or four jobs at a time to feed and clothe his growing family, will get himself a stage name (ah, that would be telling) and compere and sing in pubs and clubs around Liverpool and beyond. He will enter talent shows at places like Southport Floral Hall – but who can compete with a girl in communion dress singing Ave Maria or a dog walking on two legs while dressed as Pierrot – and when that other man who had so nearly become a priest relates these and many other stories in a crematorium sixty-something years after the queue outside the Empire, the cousin’s son will also learn that somewhere along the way (perhaps during the years when a milk round is the first job of the day) the young man will develop a liking for three Weetabix, a pint of milk and half a bag of sugar for breakfast. The son will reflect that Tate and Lyle have a lot to answer for, but what’s significant is that this habit will continue until all of his teeth are gone and after that, so what? Bring on the biscuits and sweets, which despite his best efforts the children will always find.

The almost-priest, whose plans were scuppered by Cupid’s arrow, will tell the congregation that the young man doesn’t have hobbies because when he isn’t working he is sleeping. The cousin will attest to this, since whenever he visits the house he first lived in the young man will talk and talk and then fall asleep. Perhaps the truth about the hobbies is that for him it will always and forever be about the young woman and their children, one of whom will die a year before him, and then grandchildren and great-grandchildren who will toddle around a sports and social club blowing bubbles to cheers and applause, not much younger, when you think about it, than those kids with voices of angels who took the prizes at the talent shows which our young man should have won. But he will be happy to be on stage and to be a part of something bigger, which brings us to the last words the woman will say to the man, when claims of youth have long since been set aside: ‘You’ve done your work, love. It’s time to rest.’

—

Rob Schofield, who previously received a Northern Writers' Debut Fiction Award for his novel The Queen of Kirkhill, here trades fiction for a much stranger and more tangled form: family history. His piece, ‘A Life,’ is a work of quiet and radical observation, charting a single existence as a constellation of overlapping memories, half-forgotten songs and inherited habits. Rob believes that a person's true biography is not found as much in the small, repeated detail as the grand achievements. He is currently trying to teach a pair of magpies to recite the poetry of Philip Larkin, an experiment he believes will either prove the intelligence of corvids or the ultimate futility of art.

La Violette Società 59

There is a particular, bittersweet quality to a long goodbye.

On Tuesday 25th November, we convene at Ten Streets Social for the second of our four final Società events. This is another step in the ten-year-long conversation we have been having about how to experience art together. It is another chance to participate in our quiet revolution against the tyranny of the headliner.

For this gathering, the stage will be shared by Rosy Carrick, The Rossettis, Psychederek, and Trial Tapes. Four distinct voices, brought together for one night with equal billing, equal stage time, and equal respect. The order of appearance remains a mystery to be solved on the night.

We hope you can join us as we continue our slow, deliberate and beautiful farewell.

The Gen Alpha Lexicography

by Maya Chen

08: 'Simp'

Etymology: A 20th-century American slang term for a "simpleton," resurrected by Gen Z and Alpha via Twitch and TikTok (c. 2019) to describe someone, usually a man, deemed overly eager or subservient in pursuit of affection.

My teenage son recently spent ten minutes meticulously crafting a playlist for a girl he likes. When he showed it to his friend for approval, the friend simply stared at him with an expression of profound pity and delivered a one-word diagnosis: "Simp."

And just like that, a thoughtful romantic gesture was re-categorised as a pathetic, contemptible act of self-abasement.

'Simp' is the linguistic enforcer of a new, terrifyingly pragmatic form of emotional stoicism. It is the culture's immune response to perceived neediness. The term's genius lies in its brutal efficiency: it takes the complex, vulnerable act of showing someone you care and reframes it as a shameful character flaw. To be a 'simp' is to have failed the central test of modern existence: the performance of effortless, absolute indifference.

This isn't just about romantic pursuit. A 'simp' can be anyone who displays an unseemly level of enthusiasm for anything - a musician, a celebrity, a brand. It pathologises earnestness. It turns fandom into a symptom. The underlying accusation is that you have allowed yourself to care too much, a critical error in a digital ecosystem where emotional detachment is the ultimate currency.

What makes the term so withering is that it has no counter-argument. To defend yourself against the charge of being a 'simp' is, in itself, an act of simping. You are demonstrating that you care what the other person thinks, thereby proving their point. It is a perfect, hermetically sealed trap.

'Simp' is the sound of a generation terrified of vulnerability, a generation that has learned from the cold logic of the algorithm that unrequited effort is a waste of personal resources. It is the language of emotional cost-benefit analysis. And in a world where every interaction is a transaction, showing you care before a reciprocal interest has been firmly established is, it seems, the worst investment you can possibly make.

Next time: 'Diddy Party' - When a celebrity scandal becomes the universal adjective for a disappointing social gathering.

—

Maya Chen is a linguistic anthropologist who has come to believe that all human emotion can be reverse-engineered from the slang used by her two children. Her ongoing project, The Gen Alpha Lexicography, is less an academic study and more a desperate attempt to understand why her son described her lovingly prepared Sunday roast as ‘giving beige.’ She operates under the working theory that each new slang term is a tiny, perfectly formed rebellion against the tyranny of adult sincerity. Her children, meanwhile, believe she is building some kind of secret linguistic weapon. They are, she fears, probably correct.

Somewhere In-Between

by Ange Woolf

The long door of a van slides open

Next doors dog barks

A passing car beeps

I find myself somewhere in between awake and asleep

Neither consciousness steering the ship

Like the time when the nurse softly said ‘some hot tea here love’ beckoning me to sip

But her voice tailed off as she followed a sound

To a man who thought he was crying silently inside his own head

But the whole ward was listening so she soothed him instead

Aiding his return from the dark

Allowing me to slip

The dog barks

Reality is out there but I am not quite

My feet in two dances

Two separate spheres

A consciousness voyager given a chance

To glance at what exists in this liminal place

Where blue sky fills the space

Faceless people

Silently part allowing me to see the one

I am here to see;

Myself- my oldest friend

Both actor and audience

A play without words, messages we send

They say to find peace I need to forget the choice of two

The problem between to do or not to do

If I put them aside and let them be

The problem of decision goes free

And then a third option will appear in its place

So let the questions go, no answers chase

‘Did I not do my best and love with all my heart and

Was it not they who caused the fatal blow that tore us both apart’?

The truth rolls down my red hot cheek

Not always did I give my best

Creating pain and doubt

Dysregulated feelings wreaking havoc

Leaving me without

The power of foresight

Trapped in a moment, its lessons rippling into forever

And yes, they too are not without blame, withholding all

Not letting go through sadness and shame

The thoughts that spiral in the conscious realm

Binary opposition in a war of overwhelm

Are soothing here in this dream within a dream

As a third option materialises smoothing like balm

Pressing delete on the spreadsheets of harm

‘It is clear there is only one duty and that it is LOVE

I will forgive myself for knowing no better and forgive others too

I will let yesterday stay where it is and let tomorrow through’

The van drives off

My cheek now dry

By my feet the cat has curled

A front door closes

Parcel delivered

And next doors dog continues to bark

Its joy to the world.

—

Angie Woolf reports from the liminal space between waking and sleeping. Her latest poem is a field note from this dream within a dream, a place where the harsh binary of blame dissolves and a third, more compassionate option can materialise. She has recently begun keeping two separate alarm clocks, one set to a conventional time, and the other to a random, unpredictable minute during the night, in an attempt to more frequently access this state of half-consciousness, which she believes is the only place where true forgiveness is possible.

An Incomplete History of Now & Then

by Tom Roberts

“Be there or be square.”

“Never trust a hippie.”

“If you can remember the 90s, you weren’t there…”

I loved the recent Beta Band gig in Manchester.

It was great singing along to ‘Dry the Rain’.

It’s been a while.

It was a reflective experience for me having seen them back in the days when the EPs were still EPs.

It made me think about how things work out and come full circle.

If only we’d known back then.

The talk in the car on the way back home turned to shared experiences of the rave counterculture and club scene of the 90s.

Mixed in with a bit of nostalgia and anxiety at our shared experiences.

I’m sure many of you were there.

The documentary Everybody In The Place - an Incomplete History of Britain 1984 -1992 by Jeremy Deller was mentioned and kindly shared. (Thanks Andrew.)

It got us asking:

What’s happening now?

Is there a youth movement?

What would even be considered a counterculture today?

Where is the revolutionary spirit?

I’ve always identified with the countercultural.

The ideas. The opinions. The social movements.

The music, the books, the art and the cinema.

It feels like a big part of who I am.

Everything good as far as I can tell has always been countercultural.

So this may come as a bit of a surprise to you, but I don’t consider myself to be an aficionado of the counterculture.

I don’t consider myself to be an aficionado of any culture tbh…

Ok now i've got that out of the way...

It just feels like there’s a lack of something right now, something to hold onto.

Something to believe in. Something to challenge the consensus.

That’s not just me is it? Right?

Is everything just broken?

Or am I just getting older?

Kids these days…

Did the counterculture actually win?

Are we now living in the utopia they aspired to in the 50s, 60s and 70s?

Or did they just fuck it up for everyone?

Is this the silicon dream we were promised?

A free and open interconnected world without borders or restrictions?

Nutopia, I think John and Yoko called it.

Is this what winning looks like?

It doesn’t feel like that, does it?

Some say the counterculture disappeared with the rise of the internet and the algorithmic party we now find ourselves in. ( Go on, let me have that one...)

Any spark of resistance or originality gets absorbed, flattened, commodified and instantly served back to us.

The techno equivalent of selling hippie wigs in Woolworths, man, as Danny the Headhunter would say in Withnail & I.

Everything, everywhere, all of the time.

Some say the far right have co-opted the counterculture.

I’m not sure I agree. I still see people challenging tropes and systems without resorting to exclusion, fear, intimidation or violence.

I’m all for progressive patriotism but this flag shit seems a bit weird to me.

So…

Is the counterculture now just an arts revolution?

How much can art really affect the individual or the society it’s made in?

Is counterculture just another lost future?

Is TikTok the counterculture? Instagram? YouTube?

Does the counterculture even care?

Maybe it’s me?

You know that saying:

If every room you walk into smells bad maybe check under your own shoes…

Maybe the counterculture is hiding from me.

Maybe I’m the counterculture to the counterculture.

Anyway, the reason I mention this is, all these ideas are explored beautifully in Stewart Lee’s BBC4 ArtWorks series Whatever Happened to the Counterculture?

Yes, I appreciate the irony of discussing counterculture via BBC Radio 4. But you know…they know what they’re doing.

Lee traces the evolution of countercultural ideas from the Beats, folk and jazz of the 1950s through the 60s and 70s hippies and tech-communalists, the liberation movements, punk and into the backlash of the 1980s and early 90s.

“Kill your idols.”

“Find the others.”

“Tune in, turn on, drop out.”

“Under the pavement, the beach.”

What can I say?

I don’t have the answers.

I don’t know what’s happened to the counterculture or where it’s going next.

Maybe now it's everywhere already. Dissolved into the feed.

Maybe that's the point?

I don’t know where it’s hiding and neither does this series.

But I loved it and I’d recommend it to anyone who’s looked at Stewart Lee recently and thought:

God, Matt Lockett’s let himself go…

—

Tom Roberts, who once fronted the band Cranebuilders and has a long and storied history of black fashion choices, believes that the counterculture did not die, but simply went into hiding. He now spends his weekends attempting to lure it out with a series tasty aural traps, combining the beckoning sound of Bella Freud purring extracts from Truman Capote’s ‘Breakfast at Tiffany's’ over Randy Newman’s ‘Simon Smith and the Amazing Dancing Bear’, in the hope of creating frequencies irresistible to anyone who has ever owned a copy of The Armchair Anarchist's Almanac. Tom remains convinced that true rebellion is, at its core, an aesthetic choice. His cultural choices here, much like his wardrobe, have therefore remained authentically un-ironic and defiantly chino-free ever since. Tom Roberts never let himself go.

Where You Going Now?

Valérie Bisson

Section 26 : https://section-26.fr/author/valeriebisson/

Jeff Young

Treat yourself to a hardback copy of Jeff's latest brilliant book Wild Twin :

https://www.littletoller.co.uk/shop/books/little-toller/wild-twin-by-jeff-young/

Pete Paphides

Listen to Pete’s bi-weekly Soho Radio show on Mondays 6-8pm : https://sohoradio.com/profile/pete-paphides/

Treat yourself to a record from Pete’s magnificent Needle Mythology label : https://needlemythology.com/

Tigers & Flies

Expanded Play - 100 limited edition vinyl : https://www.violetterecords.com/store/p/tigers-and-flies-expanded-play

Live Shows :

Brighton 28/10 - https://www.skiddle.com/e/41343051

London 29/10 - https://www.skiddle.com/e/41343566

York 30/10 - https://www.skiddle.com/e/41436480

Manchester 01/11 - https://heymanchester.seetickets.com/event/hey-alphaville-all-dayer-ft-tulpa-and-more/kamera-at-lloyd-and-platt/3474813

Angie Woolf

Here, there and everywhere :

https://www.facebook.com/Awordslingingwoolf/

Rob Schofield

Read more Rob here : https://www.robschofield.uk/

Nik Kavanagh

Go check out Nik’s band RUINS here: https://ruins3.bandcamp.com/music

Tom Roberts

Everybody In The Place - An Incomplete History of Britain 1984 -1992 by Jeremy Deller : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Thr8PUAQuag

What Happened to Counter-Culture? by Stewart Lee : https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m002gqy5

Beatowls’ Marma album : https://www.violetterecords.com/store/p/beatowls-marma

Violette Records

Keeping us in popping candy since 2013 :

https://www.violetterecords.com/store

Science & Magic

Back issues :

https://www.violetterecords.com/science-and-magic