Science & Magic | 12

There is a particular, clean kind of satisfaction that comes from watching someone finally face a fraction of the consequences they deserve. The news that Prince Andrew was to be stripped of all his titles delivered one such moment. A quiet, bureaucratic act, but it felt, for a moment, like a small, necessary correction to the moral fabric of the universe.

And yet, it wasn't enough, was it? The satisfaction was somewhat fleeting, immediately replaced by a hungrier, more primal desire for a more tangible form of justice. What you really want, in these situations, is something more visceral. I am, for the record, a peaceful person. But some people, man... some people make you wish for a return to a more medieval form of justice.

You watch that man, sweating pure, uncut guilt through his car-crash television interview like a cornered animal, desperately grasping at the straws of a Woking Pizza Express and a “straightforward shooting weekend,” and this subsequent, long overdue, almost gentle removal of his titles feels less like justice and more like a quiet, institutional joke. When he claims he was “too honourable,” a part of you - a primal, un-civilised part - doesn't want to see him stripped of his titles. You want to see him stripped of his skin.

It's an ugly thought, I know, but let's be honest, it’s a satisfying one.

But then, just when you think the absurdity has peaked, he’s asked about his friendship with a convicted paedophile. Does he have any regrets? "No," he says, with the smug, philosophical air of a man who thinks he's just said something terribly clever. No regrets. Not for the friendship, not for the private flights, not for the island trips and the lives ruined. No regrets for the company he kept, because through ‘adversity,’ apparently, one learns.

No regrets, huh? Okay. Well, let's see about that.

The satisfaction must return. It’s that raw, guttural need for a form of justice that can't be handled by a PR firm. A consequence that actually feels like a consequence. A reckoning so clear, so final, that it cauterises the wound and no amount of spin can ever polish it.

This desperate longing for clarity in a world that feels increasingly murky is, I think, why we find ourselves drawn to the brutal, honest geometry of a concrete car park, the perfect, un-arguable mathematics of a great melody, or the quiet, satisfying narrative of a life lived without the need for an alibi.

This edition is a collection of those small certainties. Jeff Young walking through a fever-dream version of Mathew Street where memories inherit themselves like second-hand coats, Russ Litten's unsettling short fiction about a church, a cup of tea and the terrible hospitality of strangers. Rob Schofield's timeless fable about utopia, collapse and the quiet rot that sets in at the edges whilst Tom Roberts asking whether rock music got good again. Maya Chen decoding Gen Alpha's complete personalisation of history, Jasmine Nahal's poem of fractured selves and the courage to finally arrive. Angie Woolf on hearts as structures that grow back stronger around the damage. Joe Mckechnie's Drifting Theme, born from an ex-girlfriend's text message and radical creative transparency and John Johnson answering ten questions about the soundtrack of his life.

It’s not a public flogging in the town square, I’ll grant you. But in a world of half-truths and quiet evasions, perhaps a collection of small, honest things is the only form of justice that hasn't yet been completely co-opted.

Matt

Ten Questions

by John Johnson

A city's true story is rarely found in its landmarks, but in the moments that happen beneath them. For twenty years, John Johnson has been the unofficial custodian of these moments in Liverpool. But for us, he's been something of a friend, a partner and a reassuring presence.

In the early days of Violette, no matter what strange town we rolled into, John would inevitably appear - a familiar bag over his shoulder, his trusted Nikon in hand. He was there for the love of the music, for the event, for the quiet, solitary act of documenting something he believed in. He captured some of our history, one frame at a time.

His celebrated collection, In Concert, is a testament to his process - a patient documentation of Liverpool's nightlife that has made him one of its most vital chroniclers. He finds truth in the beautiful chaos of the street and the glances between strangers. We invited John to answer ten questions, offering a glimpse into the musical map of a man who has spent his life documenting the soundtrack of his city.

● Which person most shaped your musical taste before you turned 18, and what specific record or gig did they introduce you to that changed everything?

My Uncle Tony. He passed me a cassette at the age of 12 that had Thin Lizzy Live and Dangerous on one side and AC/DC - High Voltage on the other. An absolute game changer.

● What song instantly takes you back to your school disco?

Dexys Midnight Runners ‘Come On Eileen’. Still gets the toes tappin'. A stone cold eighties classic.

● Which band from Liverpool deserved to be huge but wasn’t?

The Real People. The absolute masters of melody. I love this band both as musicians and friends. They also helped lift Oasis from second division hopefuls into genuine title contenders. Bootle's finest.

● What’s your favourite song that is from a soundtrack to a film?

‘Always Look On The Bright Side Of Life’ - Monty Python's Life of Brian.

● What song should be the new national anthem?

See above.

● What album would be most likely to trigger something and fire your brain and bring you out of a coma?

AC/DC - Powerage. Just typing that out makes me want to rock! :)

● What’s a single line from a song that has stuck with you like a mantra or a piece of life-changing advice?

"Space travel's in my blood, there ain’t nothin' I can do about it." From The Only Ones - 'Another Girl, Another Planet'.

● What was the first song you ever learned to play on an instrument (even badly)?

Del Shannon’s ‘Runaway’ - I can still play it very badly almost forty years later.

● What’s your go-to song for pure, uncomplicated, turn-it-up-and-dance joy?

AC/DC - ‘Riff Raff’ - Rock n roll in its simplest and purest form but, my word, it could move mountains!

● If you could time-travel to witness one musical moment in history, when/where would you go?

I'd head way back to 1955 to watch Marty McFly performing Earth Angel / Johnny B. Goode at The Enchantment Under The Sea Dance with Marvin Berry and The Starlighters. The reason I picked up a guitar at the age of 10 and one of the first times I felt the true power of rock n' roll. Incredible

Magnetic North

by Jeff Young

12 : Dream Street, Part One

“It was just dirt and gravel and parked-up Cortinas.” — Ghost Town

Last night I dreamed of Mathew Street, a fever-dream of memory, time travelling to childhood, to the 1960’s. Dream recollection - me walking past the Cavern with my grandad when a man stops us and asks for a light. Grandad pats his pockets, takes out his tobacco patch, finds a box of matches and strikes a match. The man leans in, cups his hands, lights his roll-up, nods and walks away, slowly, smoke-fog clouding around his greased-up rocker hair. Grandad leans into me and whispers, “He’s a Beatle. They’re going to do well for themselves, mark my words...”

The dream disintegrates like nitrate film stock, pockmarked with scorch marks, erupts into flame. I wake up, shaken by the realism of it, so real it must have happened. In truth, it didn’t happen. I have dreamed a half-forgotten radio story of mine called The Dark Corners in which I tried to make some kind of poetry of sadness from my love for my grandfather and a street in Liverpool, a place of mythic wonder that no longer exists.

Mathew Street, drab back alley, ordinary gutter of a street you’d cut down on your way to the Grapes – when the Grapes was a good pub. For some reason history kept happening here, the city dreamed visions. Old warehouses echoed to screams and electricity. If you subscribe to the mythology, it’s all explained by leylines. If you heard my performance piece 23 Enigma Vortex Sutra in 2014, you might surmise I’m mad.

By the time the 70’s came, and I was a daytime drinker in the Grapes, the Cavern was filled in and buried beneath a carpark. No site of pilgrimage, no Beatles tourism. There was, however, something volatile about the street, it had its own nervous system, separate to the rest of the city. If you were looking to undergo some kind of radical transformation this was probably your destination...

You’d walk down Mathew Street, and something extraordinary would happen – The Flamin’ Groovies hanging out on the street the morning after their blistering Eric’s gig, Shake Some Action tearing the roof off the fever dripping cellar... Ken Campbell, wild haired and pop eyed, a Mediaeval revenant scattering bones for his dog... Peter O’Halligan dressed like a sea captain, dowsing for buried rivers according to coordinates hidden in the pages of the bible, Jung’s Dream and Finnegans Wake... Ken Kesey, shamanic geriatric, speaking in acid tongues on the Magic Bus roof, destination sign reading FURTHUR... The ghost of Arthur Rimbaud passing through Liverpool, systematically deranging the senses of everyone who followed... A small boy and his grandfather, walking slowly through a dream narrative into the place where memories are invented...

If you remember things vividly enough, they eventually become myth (even if they didn’t happen). Like the haemorrhaging horse I watched dying on Goodison Road as a child, a received memory from my mother who witnessed it when she was a child. But I can still see the dying horse, can still smell its blood. I can still see my grandfather talking to John Lennon, even though it was a story I invented for the radio.

The city has its own imagination, it is a lucid dreamer. If we’re lucky enough the dream will infect us too. The small boy didn’t meet John Lennon on Mathew Street, but the street recorded the event anyway and preserved it as a memory. As much as the people who came here, perhaps it was the street itself that altered the city’s mythology.

The city is a fever dream. The street is a vaudeville theatre. The street is a Wurlitzer jukebox. The street is a transistor radio. The city is an unspooling tape recorder. The city has its own imagination. If you walk through the stag and hen parties on Mathew Street tonight you might be transformed by the lucid dreams of ghosts.

To be continued...

— Jeff Young, 12 November 2025

—

Jeff Young operates as a lucid dreamer, walking through a version of Liverpool that is constructed as much from myth as it is from mortar. His dispatches are recollections of what actually happened and field notes from what could have happened - a fever-dream of a city where the streets themselves are the narrators and where memories can be inherited like second-hand coats. He believes that if you remember something vividly enough, the question of whether it was real or imagined becomes entirely irrelevant. He is currently finalising a papier-mâché model of Liverpool based on a complex alignment of ley lines that he believes connects The Cavern Club, Goodison Park and a specific bench in Sefton Park where he once had a particularly profound thought about seagulls.

hi my name is enough

by Jasmine Nahal

I am 22 and 6 and 12 and 17 and 4

I am Punjabi and I am British and I am brown and also light

I am women who have wisdom in their bones and parts of their soul in all their children

but what if I don’t want children?

I am a fairy princess and my feet don’t touch the ground and I have green jelly clips in my hair and chocolate mousse around my face

I am a tiny lost speck, confused, homesick for something I never had

I am delicate and I am a mountain of strength and I don’t trust myself

I am a lover girl

I am trying to face the world with kindness and care because if everyone became aware, we could live in peace together

I like black bomber cheese on buttery hovis biscuits and I still think about you fondly

I have a family of lost souls in a murky soup of sorrow

I crossed the rubicon and will not let your gaping absence (yet painful presence) turn my life dark

I build worlds with the music I like, in their language I am fluent

I have a second family with my best friend

I am trying to reimburse you for being a parent

I am looking after my skin and my softness

I am still running around the kitchen with a spoon of cake batter

I have a hand stretched out to everyone

I am waiting for a vauxhall zafira to take me to my childhood and a tender ageing hand to give me my destiny

I am rich when I have nutella on toast and wildflower honey in my coffee

I am warping at the weight of being here

I am a glowy bare faced angel with curled eyelashes (but still a weird nose)

I am trying to show you as much of the world as possible because you deserve it all

I am learning to be grateful to be here

I am an artist at my university desk and my newspaper-covered, poster paint-smeared play table

I am unsure of how to spend these tokens of life

I am waiting for you to ask your mum if I can come over after school

I am hiding from the adults when it is home time

I regret not buying cake on my birthday last year

I am showing my heart in film photos I take of people I see the beauty in

I am taking steps forwards, slowly but surely

I tie red ribbon bows on the golden pothos I always wish a good morning to

I am as giddy as sleepover chatter and as quiet as the house during your nap time

I am authentic when I wear flared jeans and gold jhumkas

I am a kindred spirit to the cirrus clouds I admire

I am looking out for your face in primary school assemblies and now my phone for a birthday text that does not come

I am still waiting for the childhood hot chocolates to cool down

I am far too comfy in my cocoon

no longer, behold the contrails behind me as I soar!

alea iacta est!

I am here!

A Winter's Night with Snowgoose

There are rooms where music just seems to behave differently. The Wyllieum in Greenock is one of those places. After their sold-out show back in April, Snowgoose are returning to its intimate confines for a special, stripped-back performance on Sunday 23rd November.

For this unique evening, the band will perform as a trio. This is a rare chance to experience their timeless, harmony-rich folk music in its most essential form, built around the intricate guitar work of Jim McCulloch (The Soup Dragons, BMX Bandits) and the spellbinding vocals of Anna Sheard, with Lesley McLaren on drums. They will be joined by the brilliant Emily Scott of Chrysanths, whose own album of reflective, down-tempo piano songs was rightly celebrated upon its release last year.

Set against the beautiful backdrop of The Wyllieum, this promises to be an evening of quiet gathering to witness a band at the very height of their powers, in a room that knows how to listen. Tickets are, as you might expect, limited.

Buy your ticket here

The Church of St. John

by Russ Litten

It stood sandwiched between two terraced houses, a tall grey skinny building with a door of peeled blue paint and a single window, always curtained shut. It wasn’t anybody’s house. John had passed the building lots of times, often wondered what it was or who used it, but had never been inside. He found it fair to assume that it was a church, or some sort of place of worship on account of the simple two-lined fish carved into the stone above the entrance, but nobody he knew had ever been able to confirm or deny it. His friend Maurice, who worked down at the History Centre, didn’t know anything about the place and there was nothing in the local records to give any clue. John had bought or borrowed virtually every book available on the subject of the Avenues and surrounding area, but none of them made any mention.

On this particular Tuesday afternoon in late August, John was hurrying to the barbers for a haircut when he passed the building and noticed the door was open. Not wide open, but enough to afford a look. John stopped and peered inside. It was a dingy high-ceilinged room with a scuffed maroon carpet and dull beige walls, a dado rail running around the middle. There was another door set in the far wall, closed. There didn’t seem to be any furniture; certainly not in any part of the room that was visible.

John was torn as to what to do. He wasn’t the type of fellow given to wandering into anywhere uninvited. Generally speaking, John liked to mind his own business and expected others to extend him the same courtesy. But this was a place he’d wondered about, off and on, for a few years. Usually, he didn’t get too bothered by such things, but with a place so near to home, it was the not knowing. That stone carved fish could mean anything. He knew it was a Christian thing, the fish, but he had never seen the door open before. And now the door was open. He was early for his haircut, and the heat was making his head throb. It would be cooler in there, inside the building. He had time.

He stepped inside.

It was bigger than he had imagined. Wider. The sunlight fell from behind him and spread his shadow on the floor. It smelt faintly sweet and fusty, like a charity shop. The smell of old books and damp cardboard. John looked around. No altar, nowhere to sit and contemplate. No candles or pulpit. The room was totally empty. For some reason, he was reminded of school assemblies at Constable Street Primary, some forty-five years gone now, the taste of warm souring milk in his mouth and the floorboards hard and shiny beneath his folded ankles. The teachers dusty giants on the stage, looming over him and the rows of other children. Hands together, softly so. Little eyes shut tight. The words wandered into his mind, but he couldn’t place them. A poem? A song? He couldn’t remember.

There was a notice board on the wall to the right, three posters pinned up. John unfolded his glasses from out of his shirt breast pocket and slid them onto his face. He stepped closer. Two of the notices were pictures. One of them looked like a bird in flight, another some kind of rolling green scenery. It looked rather like something a child would draw. The third notice was just words, black type on yellow. John could see the headline in large bold capitals:

IN THE TWINKLING OF AN EYE

He couldn’t quite make out the rest.

Hello? Hello, can I help you?

The door in the far wall was open and a woman stood there. Early fifties or thereabouts, long grey-streaked hair tied back in a pony tail, plain dark jumper and jeans.

She offered him a polite, enquiring smile.

Oh, I’m sorry, said John. I didn’t mean to intrude. I saw the door was open and I thought I’d …

He didn’t know what to say, exactly. He didn’t know what he wanted, exactly.

The woman nodded.

That’s OK, she said, that’s absolutely fine. Our door is always open to visitors, she said.

I just wanted to look inside, said John. I’ve always wondered what this place was.

He made a show of running his eyes around the walls and up to the ceiling.

This is our church, the woman said. She stepped forward and offered her hand.

I’m Dina, she said.

I’m John, said John, and he shook her hand.

The woman’s face lit up.

Oh, how wonderful, she said. John! And this is the Church of St John! She took both of Johns hands in hers and shook them like a tambourine. Yes, she said, yes, yes, yes! She beamed at him, utterly delighted. John just stared at her. He felt his mouth curl into a nervous grin. He looked down at her hands. They looked so strange, wrapped around his. He didn’t quite know what to say.

You must come and meet everyone, said Dina.

She turned and led him back through the door, pulled him almost, and John had no option but to follow her down a short passageway to where a half a dozen or so people where sat around a table in a small kitchen area, men and women, most of them middle-aged or older. There was a pot of tea and a packet of biscuits on a tray, along with milk and sugar, and spoons. Books and pamphlets stacked neatly in several piles. The men and women were all looking at the doorway as he came in. They were all smiles. It was as though they had all been sat waiting patiently for him.

Everyone, said Dina, everyone, this is John! John has come to see us!

There was a chorus of John! Hello! Hello John!

One of the women got up and pulled a chair out for him.

Sit down, John, she said, please.

I can’t stay long, said John, but he sat down.

Would you like a cup of tea, John? Dina opened a cupboard above a sink and took out a mug. She sat down next to him and poured tea.

There’s milk and sugar there, she said. We have sweeteners, if you prefer those? Colin, she said, Colin, where are those sweeteners you had?

A heavy-set dark-haired man at the end of the table reached into his shirt breast pocket and produced a small yellow and white tube. He stood up, leaned across and placed the thing next to John’s drink.

There you go, John, he said.

John smiled and nodded, added milk to his tea and picked up the tube of sweeteners. He squeezed out two small white pellets, plip-plop, stirred with a small silver spoon, tapped twice on the rim of the mug and placed the spook carefully back onto the tray.

Why had he done that? John didn’t have anything sweet in his tea. He had given sugar up last summer after his father had dropped dead in the back garden whilst watering his roses. John had found him face down on sodden grass, hosepipe still running, a small pool forming around him. Heart attack. Ever since then, John had been watching what he put into his body. No sugar, no processed food, as little salt as possible. He’d stopped drinking bottles of red wine during the week and left the car at home for all local errands within a five mile radius. Movement. Exercise. His father’s death had acted as a wake-up call. Heart problems, they can run in the family, his doctor had said. John was trying to live a clean life. Five fruit and veg a day, every day, and nothing artificial. Not sweeteners. He certainly didn’t have sweeteners in his tea. In fact, John could remember trying them once and absolutely hating the taste. Bland. Synthetic. Sickly. He lifted the mug to his lips and blew gently on the hot liquid, placed it back down.

Father just before we go.

Everyone was looking at him.

He cleared his throat. So, what sort of church is this? he asked.

Oh, a Christian church, said Dina.

She picked a pamphlet up from one of the piles and handed it to him. There was a picture of people on a hill, scores of figures bathed in a celestial golden light that spilled from the clouds above them, their arms raised up to the heavens. Some of the people were lifted off their feet, they looked like they were drifting upwards, rising up into the luminescent sky.

THE RAPTURE

“We who are alive … will be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord.”

Rapture, read John, out loud. He put the pamphlet down.

What, he said, like the end of the world?

Oh no, said Dina.

More like a new beginning, said a woman at the other side of the table. She was small and blonde and chubby with bright, laughing eyes.

John looked at her evenly, tried not to smile.

You believe that you will be … spirited away?

We believe that we will transcend our earth bound bodies and live in heaven with our father, she said. She spoke gently and calmly, as if explaining something to a child.

By being literally lifted off the ground and rising up into the sky?

Yes, said Dina.

John narrowed his eyes. She smiled at him.

And when will it happen? This Rapture?

Oh, that we don’t know, she said. What we do know is that it will be followed by seven years of tribulations.

What, like plagues of locust? John struggled to keep the mockery out of his voice.

Wars, said Colin. Earthquakes, floods. Natural disasters.

Well that happens now, said John. All of that happens now.

One of the men at the far end of the table leant into to his neighbour to exchange a whispered aside. John caught the movement from the corner of his eye.

What was that, he asked. What are you saying?

The man ignored him, carried on his whispering, the woman next to him nodding slowly, yes, yes, her eyes on John.

The room felt warm. There were windows high up in the wall, but they were fastened shut and the air was still and thick. John could feel the dampness gathering under his arms. It was August. His fingers touched his mug, but it was still piping hot, too hot to drink. He didn’t even want a cup of tea. What he wanted, really was a glass of water. He opened the pamphlet and flicked through the pages. More pictures of clouds and hillsides. Barren fields and deserted cities. Planets and outer space. A huge and shadowy Jesus figure stood on a mount, his arms outstretched as if in welcome.

Hear our prayers tonight…

It’s not just natural disasters, John, said Dina. Man will turn on his fellow man.

And where are you lot when this happens, asked John, regretting his words as soon as they had left his mouth. You lot. Sounded condescending. Aggressive, even. He didn’t want to offend these people. They were clearly nuts, he thought, but this was their place, after all. He had wandered in uninvited and they had welcomed him with open arms. He had asked and they had answered.

We are all thy children here …

Those words.

We will be in heaven, said the small blond woman with the laughing eyes. She leaned across the table. Everyone will be in heaven, she said.

Well, everyone, who has accepted Jesus Christ into their heart as their Lord and Saviour, said Dina.

And what if you haven’t? said John.

Well, you’ll have to go through the tribulations, said a man at the other end of the table. You will be persecuted as a Christian. He had a long, grey mournful face, a face that you could safely assume delighted in delivering such news.

I’m not a Christian though, said John.

Wait till the Anti-Christ walks the earth, said Colin. You’ll wish you were a Christian then. He sat back, grim, resolute, fists folded away beneath his biceps.

Sounds like a threat, said John.

Nobody around the table said anything.

So what else happens in these tribulations, he said. Apart from the earthquakes and floods and the plagues of locust. What else?

Great hardship, said the woman who had been whispering with her neighbour, her voice little above a whisper now. Persecution, she said. She nodded gravely, yes. Life will be difficult for many people, she murmured.

It’s difficult now, said John.

But then Jesus will return and make his Earthly Kingdom, said the man sat next to her. He had an accent; eastern European, Czech or Polish, thought John. He couldn’t place it exactly.

Oh, so it’s not all doom and gloom then? John attempted to lighten his tone, sound jolly, almost, but there was no response in kind. Nobody laughed. But there was no animosity in the room. No tension in the silence. He looked around the table, met each of their eyes in turn and saw nothing but kindness.

This is what we pray …

John, said Di, drink your tea. It’ll go cold.

John looked down into his mug. His mouth felt dry and there was a faint sourness there, but he had no desire to lift the cup to his lips and drink. Those little white pills. Those sweeteners. He could still taste them. He looked up.

And when it happens … the Rapture … where will you be?

Be? asked Di.

Where’s the … the meeting point? The gathering place? Are you all coming here?

No, she shook her head. Sadly, this is our last day in our church. That’s why we’re a bit bare. We’ve had to take all our things out.

You’re leaving?

Case of having to, I’m afraid. The landlord sold it to someone else. A business man of some kind. A property developer, I think. They want to turn it into flats.

How long have you been here?

Around fifteen years, said Colin.

And is it an actual church?

Yes, said Di. It’s our church.

Yeah, I know, but is it … what I mean is, can you actually do that to a church? Just turn it into something else?

So it would seem, said the long-faced mournful man.

So where will you go, said John.

That’s what we need to discuss, said Di.

Keep us safe when dark is near.

It was a prayer, that was what it was. A prayer from infant school. They would say it at the end of every day, after they’d been read a story. They would sit on the mat, all of them, the entire class, their hands together softly so, their little eyes shut tight. And there was a tune to the prayer, and they would sing it, all of them together. And he would sing it again to himself later on, before he went to sleep every night, but quietly, under his breath, so his brother wouldn’t hear him at the other end of the bed. His brother was older than him and didn’t say his prayers any more, thought it was stupid, for babies. John tried to remember when he had stopped. But he couldn’t think. He couldn’t remember.

And through all the day.

His scalp prickled. His haircut. He was going to be late.

Well, thank you, said John, thank you for letting me look around.

It sounded ridiculous, saying that. Look around where? There was nothing here.

Oh John, you are so welcome, said Di.

She touched his mug of tea, turned it around so that the handle was facing him.

But come on, she said, finish your drink first.

I’ve got to go, said John. I’m going to be late.

But he couldn’t stand up. He couldn’t make his legs work. It was like they’d gone to sleep.

God, this room, it was so warm. How could they stand it?

Listen, said John, I don’t think …

His mouth wouldn’t work. He was tired, impossibly tired, and he didn’t know what he didn’t think. He couldn’t find the words. He pressed his fingers to his temples and screwed his eyes tight shut. Stars exploded, white shapes rushing towards him. He rubbed his eyes hard and then opened them again.

They were all looking at him, waiting.

—

Russ Litten is a writer who understands that the most unsettling stories rarely begin with a dramatic event, but with a quiet, mundane decision. A door left slightly ajar. A polite but insistent offer of a cup of tea. As a novelist, poet and creator of spoken-word electronica, he is drawn to the strange spaces where ordinary life brushes up against the profoundly weird. His work often explores the quiet, creeping dread that can be found in acts of unexpected kindness. He spends his days delivering creative writing workshops in UK prisons, a practice which has given him a PhD in the art of reading a room and knowing, with absolute certainty, when it is time to leave.

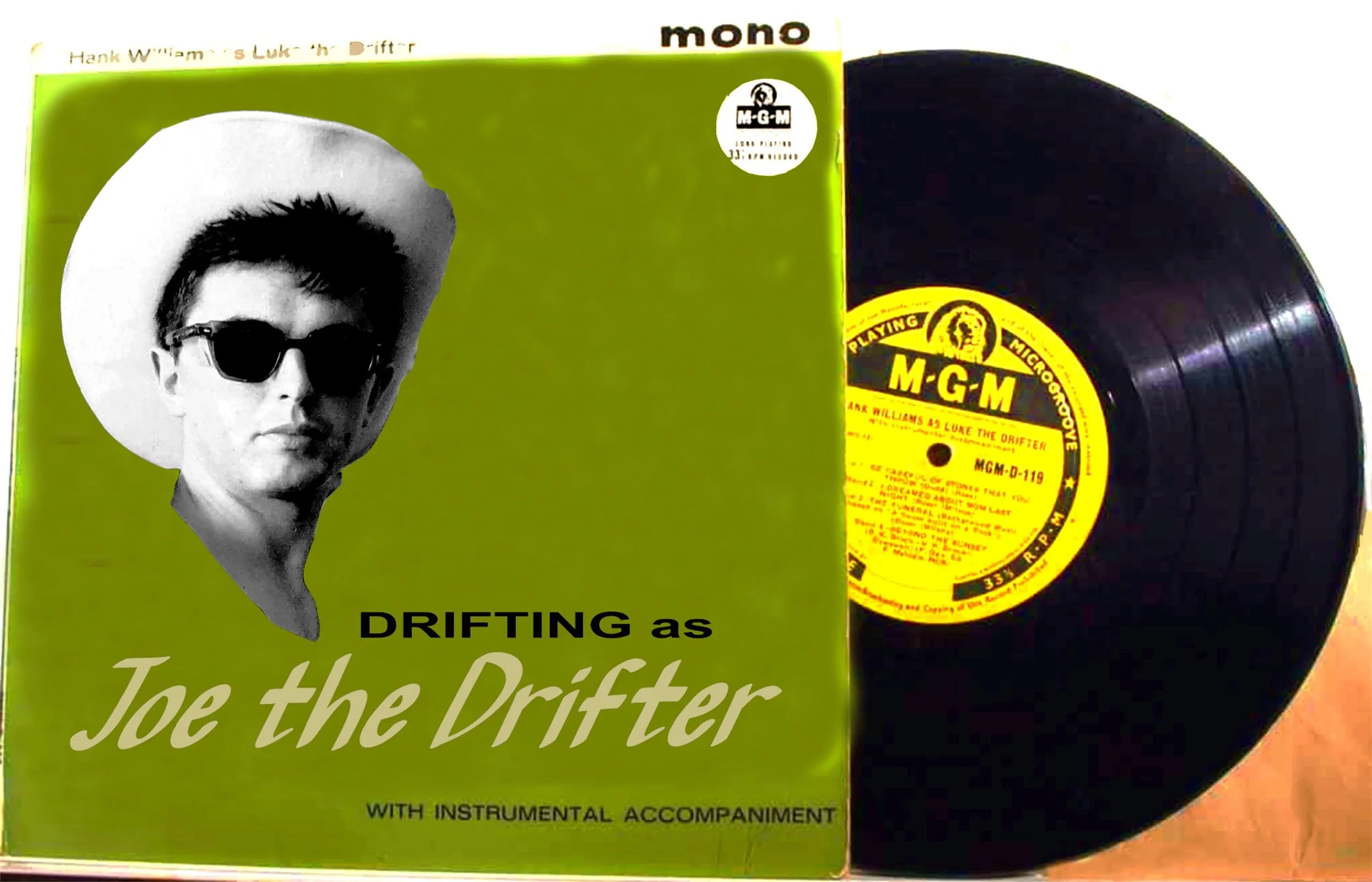

Drifting…

with Joe Mckechnie

Joe Mckechnie operates on the principle of radical creative transparency. Every interaction, no matter how fleeting or mundane, contains the raw material for a future song. A chance text message from an ex-girlfriend, a passing question about a profile picture - these are moments in a life and prompts for a melody.

His ongoing Drifting... project is a testament to his philosophy. It is a collection of aural dispatches born from the quiet, often strange, detritus of the everyday. He believes that the connection between an event and the music it inspires does not necessarily need to be obvious; it just needs to be true.

This week's piece, ‘Drifting Theme,’ is a direct result of one such exchange. The story is in there somewhere. You just have to trust him.

Photograph by Stephanie Arnold

This is a track that came out of nowhere, in that I was texting with an ex when she happened to ask who the person in my WhatsApp photo was? As we’ve not seen each other for a few years I let it go, but I did tell her that from her enquiry there would be a song.

’Drifting Theme’ is that song.

Now the connection between the conversation and the track is nowhere near obvious, you’ll have to trust me on this, it’s in there.

It’s got to be in there.

You can say what you like about the tenets of Drifting…, at least it's an ethos.

— Joe the Drifter, 13 November 2025

Like-Minded Souls

by Rob Schofield

A group of people decide to try a new way of living. Nobody knows if this is long ago or if it’s taking place now, but one thing’s for sure: if it hasn’t happened yet it’s only a matter of time. What unites these people is a belief that the best way to get things done and the most efficient, satisfying and rewarding way of living is for people to organise and do things for themselves. We might call this anarchy, co-operation, or mutual aid, but it isn’t told if they feel the need to give it a name. No one knows how these like-minded souls come together – in a village hall, hired meeting room, public house, at a music festival, a conference? – but the fact is that they coalesce around a desire to find a new way to live, since the way things are – we can all get on board with this – isn’t working for this colourful and committed troop.

Since this story takes place out of time, we can’t say – as we might if it was the 1960s – that they have had enough of working for the man, but we can say that the people aren’t looking for personal financial reward – so, not the 1980s, or now – and what they want is to try something new, with their own hands, as it were. We can imagine that they dream of a way of living in which everyone finds something to enjoy about life and is satisfied with their contribution towards this goal. A collective will for collectivism? Perhaps, but we don’t know if they would put it like that. Anyway, this group has no name and no leader, although there is a woman with a twinkle in her eyes – a cliché, I know, but there’s a reason I’m using it – who could be said to have laid down the thread that holds these like-minded souls together, and with which they find their way out of the labyrinthine mess that is modern living; until, that is, they make a shambles of their own. And how does she do this? Well, it might start with something she says or an opinion she expresses in a village hall, hired meeting room, music festival or some kind of conference. If the story is taking place as I write, she says this thing or expresses her wish or opinion on social media, and I don’t need to relay what happens next. All the people in the group can trace their involvement back to the woman – whose name, I should have said, is Ariadne – even though some of them most likely don’t know it. Some do know Ariadne, and others have heard of her through friends or acquaintances, but there are those who have no idea who she is and that it is her who expresses the opinion or says the thing that filters through the white noise of contemporary life – whenever that was/is/will be – until it reaches them and strikes a chord.

And it’s important that some of the group are not aware that, in a way, it is all Ariadne’s idea. What she says, at the origin point of this story, is something like ‘I just think, you know, that there has to be a better way to live. The way things are now is just not working.’ Later on, perhaps at another village hall/meeting room/festival/whichever social media platform/app is the current favourite when this story takes place, she says something like ‘I bet everyone in this room/tent/on this app has a talent for something, anything, that could contribute to a better life for them and the rest of us.’ And even later, she might add ‘I don’t know why we don’t up sticks and move somewhere we can start again. What do we have to lose?’ Which is what she does, egged on by friends, and friends of friends, and friends of friends of friends. Word reaches a man who owns a lot of land, but is one of those rich men – slightly better than the rest, I suppose – who wears his hair in a certain style and likes to pretend he has radical and anarchist tendencies, and this rich man, who let’s be honest does not deserve a name because in real life there are streets and buildings and businesses and foundations named after him and not the people whose blood and sweat made him rich, this rich man gives Ariadne and the other people a thousand acres.

This unimaginably large parcel of land lies in a secluded corner – is there any other kind? – of the estate the rich man inherited from his father who inherited from his father and all the way back to the original father who made his money from adults and children – he wasn’t fussed – working for scraps in his factories/on his land/in his plantations. This land is on the maps, but only in the vaguest sense since very few people have ever set foot on it. The rich man can afford to assuage his ancestral guilt – relaunching the family brand is the term his advisers prefer – with this generous gift, not least because his accountant says that the land in its present state is unproductive, and at the end of the year the donation will play well with the man from the revenue. ‘Use whatever you find,’ he tells the people. ‘It’s yours to do whatever you wish.’

A road and a river snake through the land, for which Ariadne and the others are grateful. There are lots of trees, stone walls, derelict barns and homesteads where farmers failed to scratch a living while paying rent to the rich man’s forebears. The point is that there are materials aplenty with which resourceful people can build a new society – none of them would use a word so grand – and bit by bit, something beautiful emerges. They bring in food and generators to begin with, but they plant seeds on vast reclaimed fields and dam the river and put up windmills. Soon there is power and food and even though both are limited, there is enough. The old buildings are dismantled for their bricks or rebuilt where they stand. Some, but by no means all the trees are felled, stripped and cut into planks and boards. New wooden buildings arise including a meeting hall where every week grievances are resolved, plans agreed, and decisions reached. As Ariadne hoped – as they all hoped – everyone is given the opportunity to contribute with talent or skill or experience, even – especially! – storytellers, musicians, and artists. The weather is frequently unkind, and it is far from Utopian living, but those that aren’t happy are at least able to reflect that they have a say in their present and future and only have to answer to themselves and the other like-minded souls who live in this new place which doesn’t even have a name. And this goes on for quite a long time so that children are born, some people get older, some die and some leave, but more arrive and numbers swell. What everyone agrees upon is that they have created and are living in something that is good and better than good it is special and because there are no leaders there is no one to mess things up.

It can’t last forever. And what of Ariadne? Since she is the only character with a name, something must happen to her, don’t you think? Unfortunately, as in life, there are some stories that do not have a neat and tidy ending. Ariadne appears as a catalyst, and as this is not a story about leaders – or is only about leaders insofar as it is about how they are unnecessary if and when people choose to work together for the common good – there is nothing left to say or tell about her because in the end she is no more important than anyone else in the story. Once she has served her purpose, she fades away, drops off the page and out of the story. It’s up to us, as it is with the rest of the like-minded souls, to decide what happens next and perhaps what happens next is not that they all live happily ever after, but most of them carry on living as before: not brilliant, but okay, and life is better than what they left behind. The problem is, that’s a bit of a disappointing ending. Don’t we, as tellers and lovers of stories, deserve or desire a neater/less nebulous ending which leaves us satisfied or challenged and at the very least in the mood to pass it on at some point in the future? Rightio. Here’s an alternative that provides a kind of finality for those who are more comfortable with closure:

The crops fail and fail again. When some of the people fall ill and get hungry and discover they are a long, long way from the conveniences – there are faint memories of hospitals and medical teams – of the in-no-way-perfect lives they left behind, they begin to look for something or someone to blame. Ariadne, who desired to be neither leader nor figurehead, falls into the firing line. It starts, as these things do, with murmurs and complaints on the fringes of the group; and when the rest of the group does not heed or listen to these murmurs and complaints, the people on the edge shout louder and do not stop until everyone else, many of whom are themselves tired and hungry and not feeling well, do nothing to resist the murmurs and complaints, and this is where the rot sets in. Ariadne finds herself surrounded and followed by people who whisper that the tiredness and hunger and sickness are her fault. Who is she to bring them to this place in the middle of nowhere with only one road and a river that floods, and leave them to fend for themselves? Why is she not stopping the incomers when resources are so stretched? This is not a time for the new ideas and skills and enthusiasm and commitment that these outsiders bring. And even though all decisions have been made by everyone – or those that can be bothered to attend meetings – the complainers lay the blame for their ills at Ariadne’s door and the doors of the newcomers who they follow around making threats and suggesting they leave and let the original group, some of whom have forgotten that they were incomers once upon a time, keep the land and resources they earned for themselves, it having slipped their minds that the land was a gift.

The rest of the group, or enough of the rest of the group, looks the other way – they are tired/hungry/ill, after all – when Ariadne is barracked and barged in the meeting hall and trash is left on her doorstep and when other, far worse things – unpleasant graffiti, broken glass, death threats – happen to her and the newcomers. Perhaps they are looking the other way the day that Ariadne, who is now old and yearns for a peaceful and uncomplicated life, decides she has had enough. And this is the moment where she does disappear, for good more or less, because what is left behind is central to the story and what is left behind is division and unpleasantness and, human nature being what it is, violence and – would you believe it? – a wall which is built to keep newcomers out. What the rich man or his heirs feel about a wall being erected within his estate is not recorded, but they will find a way to monetise the change through capital charges to the leasehold, since it was never told that he had gifted the freehold to Ariadne/the group of people. Those that are left inside the wall find themselves saddled with this additional burden which no doubt causes more division and strife. This is not altogether displeasing to the complainers, since they don’t think beyond complaints and destruction, while the rest of the people consider it one more thing to put up with. We have made our own bed, they reason, and will have to lie in it. Most of all, they are thankful for whatever peace they are granted whenever the complainers are asleep or plotting, and many draw comfort from the stars and dreaming of another better way of living. Actually – this is where the story ends and our heroine (if we must we have one) reappears – it is one particular group of stars: the Corona Borealis, which, as we lovers of story will find pleasing, represents the crown of Ariadne. Is our Ariadne named for the star, or vice versa? The story works either way, but in this version I’m going for the latter and will say that being too good for the world in which she is marooned, she ascends to the firmament and takes her place amongst the gods, cursed with eternal disappointment at the behaviour of the mortals and condemned to look down, the twinkle forever fading from her eyes, at the unfolding events on earth.

—

Rob Schofield here presents us with a strange, timeless fable about human nature. He builds a utopia from scratch, populates it with ‘like-minded souls,’ and then gently, methodically, shows us all the ways it is doomed to fail. Rob has a particular gift for dissecting the quiet, mundane mechanics of societal collapse - the rot that sets in with a murmur on the fringes. He is rumoured to be currently writing a children's story about a beautifully run, cooperative ant colony that is brought to its knees by the introduction of a single, deeply pessimistic woodlouse.

La Violette Società 59

The countdown continues. On Tuesday, 25th November, we host our third-to-last La Violette Società at Ten Streets Social.

This is another chapter in our ten-year experiment in collective listening. The stage will be shared equally by Rosy Carrick, The Rossettis, Psychederek, and Trial Tapes. The playing order, as always, is left to fate.

We hope you can join us or another step in our long goodbye.

The Gen Alpha Lexicography

by Maya Chen

10: 'Era'

Etymology: Historical term for a long and distinct period, co-opted by pop culture (specifically Taylor Swift fandom) and repurposed by Gen Alpha to describe any fleeting personal phase or mood.

Last week, my son announced he was entering his ‘villain era.’ The catalyst for this dramatic shift in personal alignment was not a traumatic betrayal or a thirst for world domination. It was my refusal to buy him a specific, overpriced brand of fizzy drink. He spent the next forty-five minutes sighing dramatically and staring out of the window with the practiced melancholy of a tortured romantic poet, before abruptly ending his villainy when I offered him a chocolate biscuit.

Welcome to the 'era' - the fundamental unit of time in the Gen Alpha universe. The term has been completely unmoored from its historical meaning. An 'era' is no longer a significant, multi-year period defined by major geopolitical events. It is now any transient personal aesthetic that lasts for more than a fortnight.

We are living through the complete personalisation of history. My daughter recently had a ‘corduroy era,’ a ‘reading-by-candlelight era,’ and, for one particularly trying weekend, a ‘speaking only in questions era.’ Each phase is treated with the gravity of a major cultural epoch. They are not simply 'trying things out'; they are curating their own personal timelines, complete with distinct, named periods that can be retrospectively analysed for their thematic significance.

This isn't just self-obsession; it's a form of narrative control. In a chaotic world, defining your life as a series of distinct, manageable 'eras' imposes a sense of order. It turns the messy, unpredictable business of growing up into a neatly curated series of chapters. Your "sad girl era" isn't a period of genuine distress; it's a stylistic choice, an aesthetic to be performed until the next one comes along.

The ultimate absurdity is that these eras require no substance. My son’s ‘villain era’ involved no actual villainy. It was simply the performance of being a villain - a mood, an attitude, a temporary branding exercise. History has been replaced by personal marketing. And in a world where everyone is the main character of their own story, it makes a strange kind of sense that they would also want to be their own historian, diligently naming each brief, fleeting chapter of their own magnificent, unfolding epic.

Next time: 'Ate' - The highest form of praise, awarded for any act of moderate competence.

—

Maya Chen receives transmissions from language. She believes that slang is a sentient, hive-mind entity that has chosen her as its unwilling oracle. Her articles are part analysis, part automatic writing, dictated to her during fugue states which she can only induce by listening to algorithmically-generated ASMR videos of people unboxing rare trainers. She files her copy from a small, lead-lined room in her basement, which she claims is the only place shielded from the ‘psychic background noise of dying memes.’ Her children are forbidden from entering, not for her privacy, but because she fears their unfiltered digital consciousness could cause a feedback loop that might, in her words, ‘make the entire concept of Thursday spontaneously combust.’

Heart Work

by Ange Woolf

Words that aren't spoken

Still felt by the heart

Unseen by the eye

Their colours impart

Like bruises unhealed

Making holes in the walls

Gaps appearing

Where darkness can crawl

The damage looked deep

The doctor had said

It should have stopped time

Left them for dead

But around of the holes

The walls had grown back

Affixed by a bond

That sealed off the cracks

Cemented by hope

No fear of rebuff

Open for business

The power of Love.

—

Angie Woolf recently gave up observing people for a week and turned her attention to her city's quiet, ongoing work of self-repair. She maintained a meticulous photographic archive of expertly patched brickwork, mismatched paving stones and the elegant, almost sculptural, application of gaffer tape on cracked window panes. She believes these are ‘scars of resilience’ - the physical evidence of a city refusing to fall apart. Her latest poem, ‘Heart Work,’ applies this principle to the human soul, arguing that the most beautiful parts of us are the places where we have been carefully, lovingly, put back together.

L'homme Qui Aimait Les Pochettes

Exposition et table ronde

À PROPOS

—

Chèr(e)s ami(e)s,

Du 1er au 29 novembre, la médiathèque Violette Leduc (Paris) accueille une exposition consacrée à mes réalisations graphiques pour des artistes de la scène musicale française et internationale.

Un retour en images sur près de 15 ans de collaborations, pour vous présenter une sélection forcément difficile et subjective (tant elles célèbrent toutes une rencontre artistique dans mon parcours), de pochettes de disques, d’affiches et de sérigraphies.

En clôture de l'exposition le 29 novembre, une table ronde explorera le processus créatif derrière la conception d’une pochette.

Animée par Yolande Garrido, elle réunira Laure Slabiak, François Gorin et moi-même pour un échange autour des liens entre musique et image.

En avant-propos, Christophe Basterra m'a fait le (très) grand plaisir d'écrire quelques mots pour présenter cette exposition.

Au plaisir de vous y voir !

Pascal Blua

Médiathèque Violette Leduc

18-20 rue Faidherbe, 750111 Paris

Espace accueil, entrée libre

Table ronde le 29 novembre (15:00 / 17:00)

Gratuit sur réservation : mediatheque.violette-leduc@paris.fr ou 01.55.25.80.20.

Did Rock Music Get Good Again?

by Tom Roberts

Is it me or have the Americans reinvented rock music again?

Maybe it’s just me getting excited about things the rest of the world ignores.

I’ll roll back the rhetoric but still...

OK let’s get this down before I change my mind and start listening to something else.

Do you even care? And why don’t you even care?

Rock music has always been derivative.

The best stuff does what it says on the tin. It rocks. That’s it.

Who doesn’t love to rock from time to time?

Every generation rediscovers the same electricity, plugs it back in, calls it new.

A little like the things I’m saying here and the piece I’m writing now.

Originality?

Overhyped. Mostly a myth.

Besides, if a band has never done it before, isn't it new to them?

Now I’m not really an aficionado of rock music.

I’m not an aficionado of any music to be honest, but two recent records spinning in my house are Wednesday’s Bleeds and Geese’s Getting Killed.

Just when I thought I was out they pull me back in

Karly Hartzman and Cameron Winter have tapped into something familiar and something completely untamed. And then there’s Water from Your Eyes’ It’s a Beautiful Place which I’ve been loving as well. It sounds like pop music falling apart and figuring out how to keep going anyway.

I hear something crackling under the surface across these records.

Not reinvention but reanimation.

You can hear the echoes of rock history in them.

The twang and pedal steel of Southern rock in Wednesday, the sharp angular grooves of Television and Talking Heads mixed with Exile era Stones in Geese, the art rock and glitch-pop edges of Water from Your Eyes.

It’s all there, the ghosts, the grit, the shimmer

Maybe rock music’s the same.

It’s not the sound of the record that’s changed.

It’s the way we reinvent it at this moment in our lives.

In 2025, after a decade of hyperpop, post-everything irony and algorithm-driven music, these records feel messy again.

Human again.

Real again.

Geese stretch classic rock structures, inventing a world of possibilities while finding a strange balance between control and chaos.

Wednesday combines noise, alt-country and small-town storytelling into something rough-edged but deeply human.

Water From Your Eyes twists art pop and post-punk into sharp, awkward, intelligent tracks that somehow make sense.

You hear the ghosts of the past, yes, but you feel the electricity and energy of now.

Or something like that…go and listen to them.

Make up your own mind.

So maybe Americans haven’t reinvented rock music.

Maybe it doesn’t need reinventing.

And maybe this is just a list of three random records I like and have pulled together to complete another deadline. I could’ve included Prewn’s System.

I definitely should’ve included Prewn’s - System…

Maybe the thrill comes from hearing it alive again, messy, imperfect and realizing that what we call “new” is often just a matter of paying attention.

As William Blake put it, “The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way”.

Maybe it’s not the sound that matters.

It’s the way that you hear it.

—

Tom Roberts believes that the primary function of rock music is to make you want to kick things, but in a thoughtful, slightly melancholic way. He approaches new records with the cautious optimism of a lifelong Everton supporter who has learned that hope is a dangerous and often foolish investment, but one that is ultimately unavoidable. He was recently seen trying to teach his cat the difference between the guitar tones of Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd, an experiment that apparently ended with the cat sighing, knocking over a cup of tea, and leaving the room with an air of profound disappointment.

Where You Going Now?

Jeff Young

Indulge yourself with a hardback copy of Jeff's latest brilliant book Wild Twin :

https://www.littletoller.co.uk/shop/books/little-toller/wild-twin-by-jeff-young/

Tigers & Flies

Expanded Play - 100 limited edition vinyl : https://www.violetterecords.com/store/p/tigers-and-flies-expanded-play

Snowgoose

A Winter's Night with Snowgoose - Sunday 23rd November, The Wyllieum, Greenock Buy tickets here: https://buytickets.at/violetterecords/1853729

Russ Litten

https://russlitten.co.uk/

Toria Garbutt

Eimear Kavanagh

John Johnson

View John's celebrated "In Concert" photography collection and more: Instagram https://www.instagram.com/johnjohnsonphoto/

Angie Woolf

Ange, Ange, Ange :

https://www.facebook.com/Awordslingingwoolf/

Rob Schofield

Read more Rob here : https://www.robschofield.uk/

Pascal Blua

L'homme Qui Aimait Les Pochettes - Exhibition at Médiathèque Violette Leduc, Paris (1-29 November) Table ronde: 29 November, 15:00-17:00 Reservations: mediatheque.violette-leduc@paris.fr

Tom Roberts

Beatowls’ Marma album : https://www.violetterecords.com/store/p/beatowls-marma

Wednesday: wednesdayband.bandcamp.com

Geese: geesebandnyc.bandcamp.com

Water From Your Eyes : waterfromyoureyes.bandcamp.com

Prewn: prewn.bandcamp.com

Violette Records

Keeping us in popping candy since 2013 :

https://www.violetterecords.com/store

Science & Magic

Back issues :

https://www.violetterecords.com/science-and-magic