Science & Magic | 14

Spotify Wrapped served up its annual reports this week. You know the drill. A cheerful, brightly-coloured infographic arrives, unbidden, to inform you that your entire year of private listening can be neatly summarised into five genres, a ‘sonic aura,’ and a congratulatory message confirming that you are in the top 1% of listeners for some obscure, melancholic folk artist you played once, on a Tuesday, when you were feeling particularly sorry for yourself.

I find the whole exercise deeply irritating. Not because it's inaccurate, but because it's so terrifyingly, stupidly accurate. It is the digital performance review I never asked for, a diagnosis of my own predictability. The algorithm, a well-meaning but profoundly stupid robot, can tell me that I listened to ‘Once I Loved’ by Astrid Gilberto forty-seven times. But it cannot distinguish between the listens that were for pure, aesthetic pleasure, and the ones that were a form of intense, self-inflicted emotional punishment. It files them all under ‘Top Songs,’ reducing the complex, messy business of being a human to a shareable data point.

This is the tyranny of our age. It’s a gentle, persistent and terrifyingly effective project to sand down our sharp edges, to smooth our eccentricities into a pleasant, predictable and marketable sludge. The machine learns what we like, shows us more of what we like, and in doing so, quietly, surgically, removes the possibility of any happy accident or glorious mistake or that life-altering discovery of a record you picked up because the sleeve looked interesting. I feel boxed in by this shit and I don’t like it.

This, I suppose, is the very soul of Science & Magic. A celebration of creativity, with all its flaws, biases and beautiful, un-scalable inconsistencies. In this edition Tom Powell maps a life in music from elevator themes to Tanzanian playlists. Jeff Young watches his favourite cinema fall and catches stars in cigarette smoke. Pete Paphides emerges from recalibration with Northern Soul horns and the longest day on repeat. I point to cathedrals as seaside chip shops lamenting the recent passing of Martin Parr. Amy Collins reconstructs three decades around a black cab and the precise science of chippy queues. Jasmine Nahal arrives alone in Leamington Spa wearing the right boots and discovers she isn't lonely. Maya Chen decodes the death of trust. Ange Woolf speaks for the pigeons, who were here first and ask only for kindness. And Fiona Bird - temporarily occupying Tom Roberts' abandoned chair - surveys the wreckage of independent music and finds brilliance working in the dark for an audience of nearly nobody. The usual magic, the usual despair, the usual refusal to look away.

This is what you’ve found in the ruins of a perfectly good algorithm. Welcome to your latest edition.

Matt

Ten Questions

by Tom Powell

I first met Tom Powell back in May 2016, at the second of our La Violette Società nights. He was playing bass for We Are Catchers, and I remember being struck by the quiet, intelligent confidence of his playing. It was no surprise when he later answered the call to become an essential part of Michael Head & The Red Elastic Band.

He joined alongside his friend Phil Murphy, the drummer from that same We Are Catchers line-up. Together, they formed a formidable rhythm section that brought a new, versatile and intelligent energy to the band. Tom’s bass work is exceptional, simultaneously showing a deep respect for the legacy of Head’s music while always bringing fresh ideas to the table, a role he has inhabited with grace and formidable talent.

As the son of legendary producer Steve Powell (our guest in Issue 9), Tom's roots run deep in Liverpool's musical soil, but he has forged his own distinct path. This same spirit infuses his brilliant solo project, deffo, which moves from the dystopian, space-based trip-hop of last year's Music for Dinosaurs to the psychedelic folk-rock of his forthcoming third album, All Or Nothing.

Tom is one of the most intelligent, grounded and music-obsessed people I've had the pleasure of working with. We invited him to select ten questions from our archive, and his answers reveal a musical map charted by a 60s-obsessed adolescence, a life-changing trip to Tanzania and an unexpected, enduring love for the Ghostbusters theme tune.

● What's your favourite song from a film soundtrack?

Elmer Bernstein - ‘Main Title Theme’ (Ghostbusters). (Not to be mistaken with the ‘Who You Gonna Call?’ theme tune…!) Ghostbusters was my favourite film as a child, and I still love it today. This piece of music always gives me a lift - which is ironic as it could easily be mistaken for elevator music in passing. It’s always given me an otherworldly feeling but in a more positive way than may have been intended given the subject of the film.

● What song became the anthem of your first teenage friendship group, played endlessly?

Ocean Colour Scene ‘The Riverboat Song’. When we were about 15, me and my mates Toby and Danny would get a load of cans and head to a local park on a Friday night; we’d end up singing this acapella all night.

● What genre or artist did you come to embarrassingly late, kicking yourself for missing out?

In my late teens-early twenties I was a devout 60s-music nut and wouldn’t entertain much else from any other era. I was that precious about it, even to the point of walking out of bars if something too contemporary was playing. The pinnacle at the time was the song 'Kids' by MGMT; it was everywhere, and I hated it with a passion. Looking back, I definitely missed out by shunning this and much else of the great music kicking about at the time.

● What album would you press into the hands of an 18-year-old today, insisting they listen to it front-to-back right now?

The Strokes - Is This It. At that age you need something exciting with attitude and swagger to grab your attention, and this is it for me.

● What song is permanently fused to a specific place or holiday—to the point where hearing it transports you instantly?

Toto ‘Africa’. Likely considered quite a cheesy song to many, but it takes me back to putting together a playlist when I was prepping to go and live in Tanzania in my early 20s.

● What's your favourite sound that isn't music?

Being away from home in a foreign land and hearing an unknown language being spoken, combined with the sounds of an exciting and unfamiliar territory.

● What's your favourite cover version of someone else's song?

Fontaines D.C. ‘Cello Song’. The original (Nick Drake) is my favourite song. Fontaines are my favourite band of modern times, so this was an unexpected match made in heaven for me.

● What new artist or band are you most excited about right now?

Continuing my praise of Fontaines D.C. - their past couple of albums have blown me away, and they keep getting better and better. I met them briefly this summer and they were as equally cool as their music.

● What's the last album or song that made you stop whatever you were doing and just listen?

The Verve ‘Sonnet’. I listened to this on my cans last night, what a phenomenal combined craft of music and songwriting. I went to see one of the Oasis shows over the summer and it was a stacked bill of legendary songsmiths, but Ashcroft and this beauty in particular blew me away.

● What song would you send into space to represent humanity?

Minnie Riperton ‘Les Fleurs’. Perfectly crafted, not a second of spacetime wasted, and a chorus that demands your ears. Fire up the rocket, turn it up loud and blast off.

Magnetic North

by Jeff Young

14 : Moonbeams

Beneath a silver moonbeam I am watching cigarette smoke phantoms rise through flickering light, a magical dance of apparitions. The dream visions of angels and demons on the cinema screen are beautiful but so too are these wraiths, these ethereal spirits. When you fall in love with cinema you’re not just falling for the visions on the screen, you’re also enchanted by atmosphere, by the poetics of place. Here in the cinema of my childhood, in the cigarette smoke filled darkness, there are gunslingers, lovers kissing, rocket ships to distant stars, detectives lit by neon. There are damp overcoats too, and the smell of Player’s No 6 in ashtrays. Here we are in dreamland...

Oftentimes I write about the old days. Not - hopefully - in a misty-eyed, things were better in the old days’ way, because, of course, things were not better in the old days. I write about remembering as a way of paying close attention to the then and the now, the before and after, the noticing of change. One day you notice that the cafe or crooked corner you loved is no longer there and you miss it, miss the familiarity. The light on that street you used to love on summer evenings is no longer there because that new hotel has plunged the street into shadow. Sometimes you watch change happening before your eyes slowly. Sometimes it comes as a shock, like the time I stood in a shop doorway on Lime Street and watched my favourite cinema being demolished.

In Ghost Cinemas, the track I made with Joe McKechnie for his brilliant Drifting project (posted by Joe in the 13th edition of Science & Magic) I mused on the poetic and emotional potency of picture houses and how they are – or were - a kind of memory palace haunted by ghosts of courting couples, specifically my mother, and how, when she was young she would “travel by bus or tram to cinemas all over the city, the names of the picture houses like glamorous destinations, distant stars: Futurist, Essoldo, Majestic, Scala, Palais De Luxe, Rivoli, Trocadero...a dazzling, electric galaxy of rapture.”

Like my mother I have spent much of my life sitting in cinema darkness, in awe, feeling like my heart is filling up with constellations, never, ever getting over that feeling of cinematic transcendence, dream and desire, where horses and scuba divers, soldiers and astronauts, talking animals and monsters, goddesses, gods and gunslingers illuminate the dark.

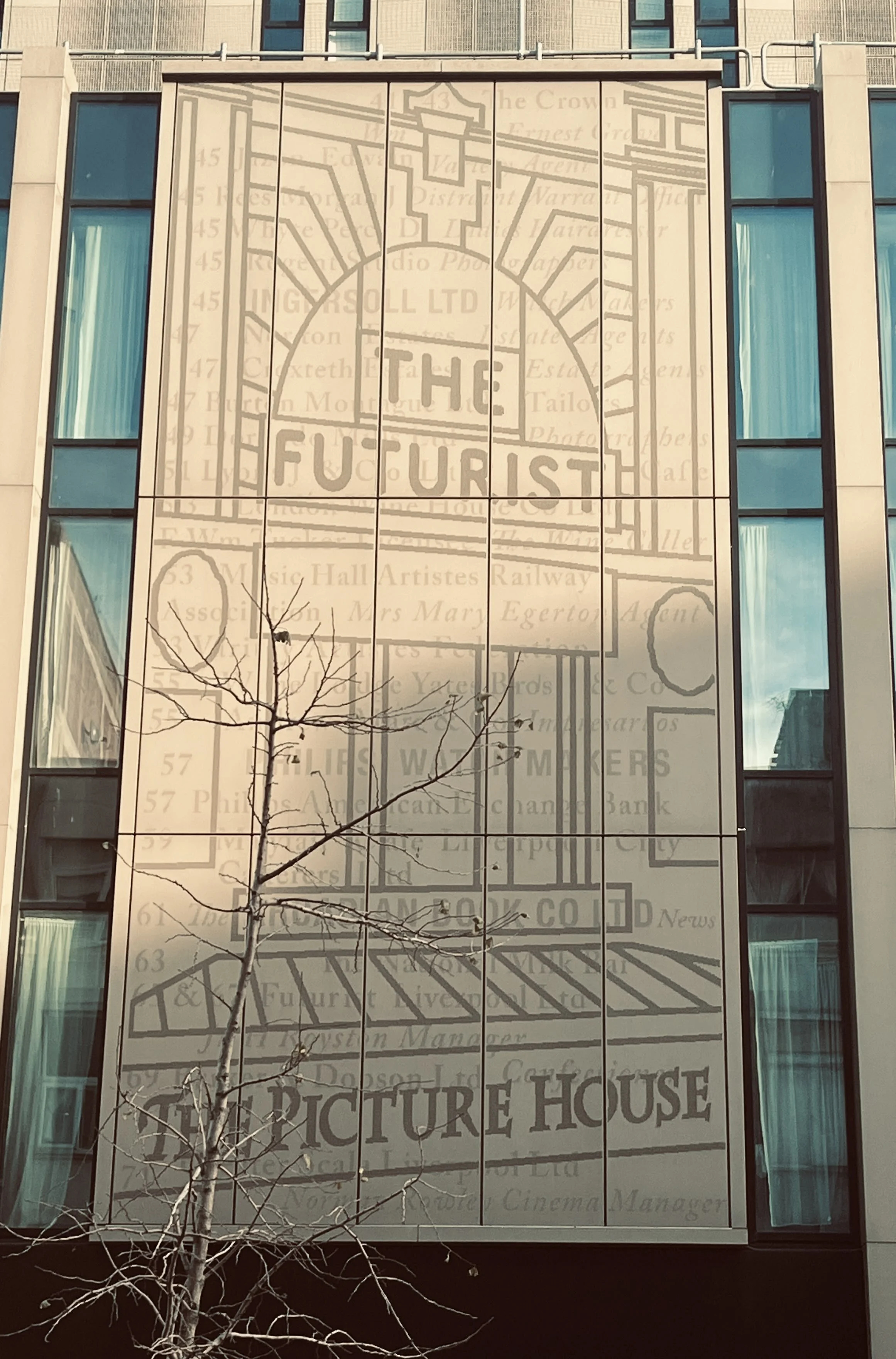

When the Futurist was demolished, they promised us they would honour the memory of that beautiful, haunted building.

They built this hideous fridge magnet instead.

All we have is memory, moonbeam and darkness where we become astronomers in dreamland. If we reach up into the beam of light, smoke ghosts curling around our fingertips, we can catch the falling stars.

— Jeff Young, 9 December 2025

—

Jeff Young will be spending the Christmas period in a state of what he calls ‘deep temporal listening.’ He intends to sit in his living room with the television tuned to a dead channel, believing that the resulting white noise contains the ghostly echoes of every Christmas special ever broadcast. For New Year's Eve, he plans to walk the entire length of a deserted Mersey beach at low tide again, a ritual he claims allows him to ‘read the receding year's final thoughts in the patterns left on the wet sand.’ His dispatches will resume after he has successfully translated these findings into a new, and likely unsettling, map of the city's emotional geography.

The Paphides Principle

Some critical instruments require periodic recalibration. For the past few weeks, Pete Paphides has been on a mandatory sabbatical - a period of quiet listening and sensory deprivation designed, we are told, to reset his palate and purge the lingering residue of lesser melodies. This is a necessary part of the process.

He returns from the wilderness with his senses sharpened and his critical faculties honed. The Paphides Principle, our fortnightly correction to the algorithm, resumes its essential work.

This is his first pronouncement since the recalibration.

The Just Joans - ‘Limpet’

My love of songs about being a parent long predates my own years of caring for small humans. It started with Brotherhood Of Man’s ‘Save Your Kisses For Me’. Back then, it didn’t occur to me that a song about loving your offspring was, in pop terms, a relative rarity. I was seven and my mum was constantly telling me how great I was, so why shouldn’t there be loads of songs by other parents who also thought their kids were great? A few years later, I heard ABBA’s ‘Slipping Through My Fingers’ – think ‘Where Does All The Time Go?’ refracted through a bleak filter of Nordic gloom – and I was suddenly pondering the desolation of the empty nester years before I’d even hit puberty.

The marvellous new single by The Just Joans – their first in five years – isn’t quite so heavy on the emotions. It’s called ‘Limpet’ and it was written by guitarist David Pope shortly after his son was born. He wanted to zone in on the “wonderful messiness of life with a newborn” whilst also touching on some of the stuff that you can no longer get up to (“getting drunk and snogging strangers”, as he puts it). He wrote it from a female perspective because, for women, “the all consuming nature of the experience is altogether more oppressive” – which doubly makes sense given that his sister Katie is the band’s singer. Along with the rousing refrain, “Every single day is the longest day”, the four-to-the-floor beat and parping Northern Soul horns will, to paraphrase Graham Gouldman and Andrew Gold, build a bridge to your heart and rightly ramp up anticipation for the group’s new album Romantic Visions Of Scotland, which lands on January 23rd.

—Pete Paphides, 10 December 2025

Shadow Songs

by John Canning Yates

What better way to wrap up 2025 than with one of my favourite songs from 2024? I first heard it just before my own album The Quiet Portraits was released. Music often becomes synonymous with the space you’re in, and this one always takes me back to a dreamy trip through the French countryside, the landscape drifting by, heading to play a gig in Nantes, leaning on the window sill with my headphones on. The Blue Nile’s Hats and ‘Sadness as a Gift’ by Adrianne Lenker, on repeat.

It’s such a beautiful song that it almost feels sacrilegious to cover it, but again, I just felt like living inside it for a little while. Apparently, the song was born from a conversation with her therapist, who said that the sadness we feel is a reflection of the love we carry within us. A Bruce Forsyth note to self: find a therapist who can inspire songs as beautiful as this.

Here’s my own version, recorded at a time of year that inevitably led to the inclusion of sleigh bells.

— JCY, 10 December 2025

—

John Canning Yates is becoming less a musician and more a human antenna, standing on the roof of his industry at 3am, catching the ghost frequencies that other artists sleep through. He operates like a noir-dimension ‘Whispering Bob’ Harris - if Bob broadcasted from a candlelit room where the piano keys are made of human bone and the songs have shed their daytime skins to tell their truth. As curator of the ‘Shadow Songs’ series, John’s recordings are whispered notes from the edge of sleep, capturing the beautiful, sleep-deprived logic of a song communing with itself in the dark.

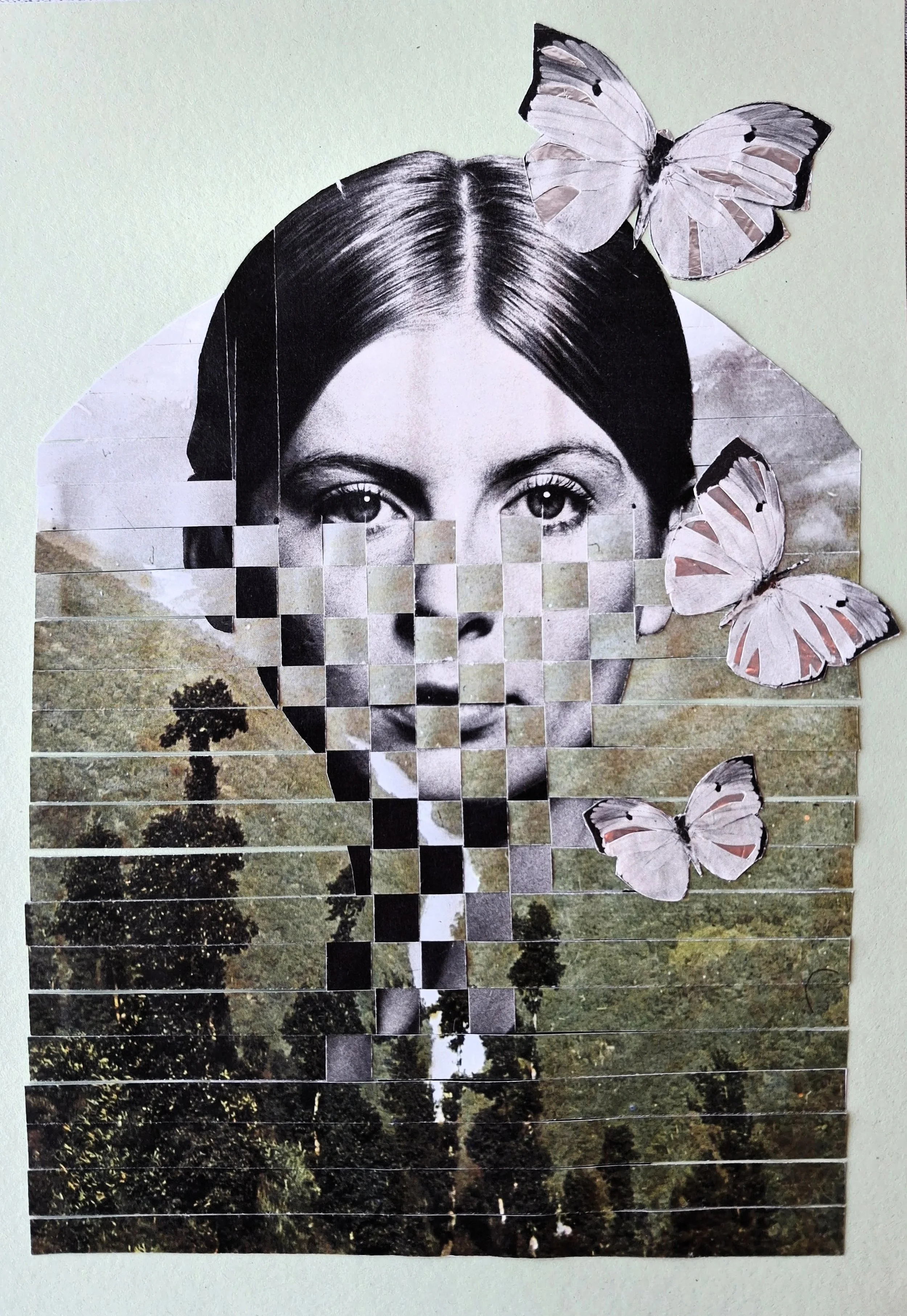

What Am I Piecing Together That Refuses to Stay Whole?

by Eimear Kavanagh

Piecing together I try

What refuses to stay whole

An equal equilibrium

A peaceful residing soul

Love & Good Tidings, Eimear

—

Eimear approaches artistic practice with the focused, rhythmic discipline of a master knitter and the free-form, primal energy of an alpine yodeller. She claims to have learned a unique colour theory from studying the complex, clashing patterns of a half-finished Fair Isle jumper she discovered in a charity shop. Eimear will be spending the Christmas period attempting to knit a perfect, seamless sphere and has resolved to learn one new, entirely useless skill before the New Year.

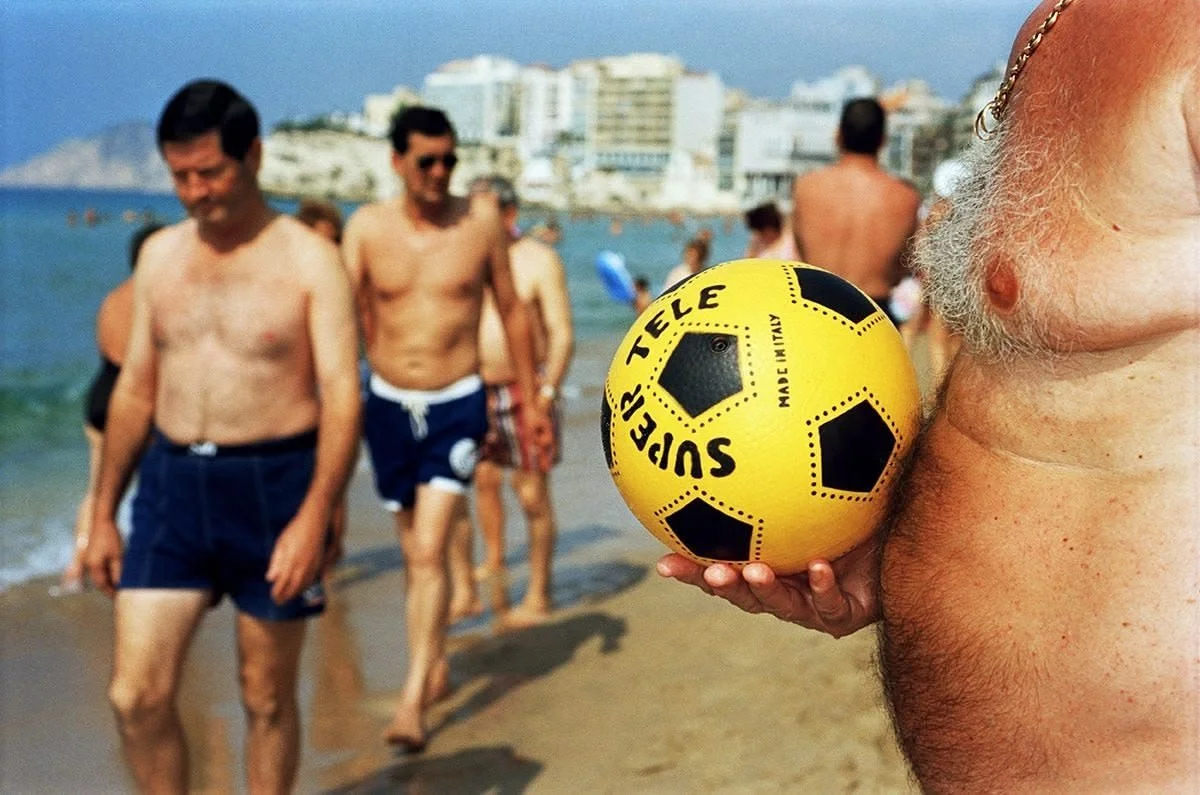

On Seeing Ghosts in Saturated Colour

by Matt Lockett

I first encountered Martin Parr’s work, as many did, through a battered library copy of The Last Resort. It was the early ‘90s, and I was living in a Manchester that seemed to be rendered in shades of grey. Then this book arrived, a collection of photographs from New Brighton so violently, beautifully colourful it felt like a transmission from a much stranger, more honest planet.

Here were ‘northerners at play’, captured with an unblinking, almost anthropological eye: a woman eating chips from a paper cone, children staring at ice creams of a patently unnatural hue, an overflowing bin against a leaden and luminous sky. The colours were the first thing that hit you. The lurid, hyper-real saturation made the mundane landscape of a declining seaside resort look both sacred and profane. It was beautiful. And it was brutal.

The predictable, pearl-clutching horror from the London art world that followed was the greatest endorsement he could have received. They saw a southern, middle-class photographer sneering at the northern working class, turning them into a ‘sitting duck for a more sophisticated audience.’ They’d call it ‘poverty porn’ today. They missed the point entirely, of course. What they interpreted as sneering, I recognised immediately as a kind of unsentimental affection. It was recognition.

Martin Parr’s work especially resonated with me because it felt connected to this quiet lineage of photographers I was also discovering at the time - snappers who found a strange, stark beauty in the unvarnished reality of British life. His pictures belonged alongside Tom Wood’s photographs of the Chelsea Reach pub, with Paul Graham’s documentation of life in the lay-bys of the A1, with the brutal, claustrophobic tenderness of Richard Billingham’s family portraits and with the surreal, gentle absurdity of Tony Ray-Jones’s pictures of the English at their most un-selfconsciously weird. They were all engaged in the same project: telling the beautiful, awkward truth.

Parr’s talent was probably in his refusal to look away from the messiness, the absurdity, the quiet despair and the defiant joy of it all. He understood that the fluorescent glow of a chip shop could be as revealing as an ancient cathedral and that the colour of a plastic beach bucket could anchor the entire mood of the viewer, that the way a stranger holds a sandwich speaks of class, of longing and place.

This obsession with cataloguing the mundane is what led to what might be his most quietly brilliant and misunderstood work: his books of postcards. I remember finding a copy of Boring Postcards in Dillons bookshop in St Ann’s Square and feeling that same jolt of recognition. Here were hundreds of photographs of civic centres, ring roads and multi-storey car parks, each a testament to a particular kind of post-war municipal ambition. Most people would see nothing but concrete and failure. Parr saw poetry. He understood that these utilitarian structures were, in their own way, monuments to a kind of hope, a belief in a future that never quite arrived. In Parking Spaces, he photographed ‘the last parking space’ available in 41 countries - articulating the ‘individual frustration of finding somewhere to park, but on a global level.’ It’s a masterpiece of finding the sublime in the ridiculously ordinary.

In an age that demands glamour and an ultra aspirational narrative, Martin Parr had the courage to tell a different, more honest story. He gave us permission to find beauty in the glorious, messy, slightly disappointing reality of the world we actually live in. He wasn’t just a photographer; he was a teacher. And he taught us all how to see.

Taxi Driver

by Amy Collins

My earliest memory is of that taxi, along with pure panic and abandonment: teetering on the step of our terraced house in Pensarn Road, watching Mum, Dad, and some fella fuss around the hackney cab in the street. Bitter diesel fumes, choking engine noises, Scousers shouting frantic instructions. Then a cheer as the cab spluttered to life. I watched them vanish around the corner, still pushing. I was three, so I didn’t know what a jump-start was or that Mum would be back in less than three minutes. I imagine I was hysterical by then.

That shiny black cab was never just a car to us, or even just a livelihood, it was a totem and family emblem for nearly thirty years. Driver and cab were fused together like a tortoise to its shell; all our lives revolved around it. It was Dad’s portal into the community and the filter through which he saw the world. Through a grimy windscreen, he saw Liverpool’s litter, pollution, and crime. Over his shoulder, there were prostitutes, smackheads (his words), and people clawing through life. Doctors, celebrities, and global travelers climbed in, but it wasn’t the glamorous fares driving him to move me and my pregnant mum from Old Swan to North Wales in 1987 – it was a stubborn desire for us to grow up in the countryside.

It must have been a novelty for the residents of Pantymwyn to see this rattling, misplaced relic driving around. You can’t be inconspicuous when your car sticks out like a sore thumb, your parents sound like they’ve walked off the set of Brookside, and your dad is the spitting image of Paul McCartney. Our schoolmates thought it was ace; they’d only seen black cabs on the telly on EastEnders. Dad thrived on people’s curiosity and entertained them with taxi tales and Liverpool one-liners. He sometimes offered lifts, pulling up at the bus stop, on rainy days to rescue people waiting for the sluggish hourly service. A lot of charm work went into distracting the affluent locals from noticing we were Edge Lane’s answer to the Clampetts!

Aside from two weeks in Cornwall and one sacred day trip a year to Alton Towers, Joe was always back in Liverpool, working long-collar. To squeeze in time with his children, he’d simply take us with him. Me first, then our Jen when she was old enough, and later our Paul. I’d clamber into the luggage bay at the front next to him with a couple of cushions from our settee in the house. I’d been prepped with drills of throwing his fleece over my head and keeping still in case the police were sniffing around. The 40-mile commute was uncomfortable, diesel fumes stinging my nose, but I was excited, so I didn’t complain. My eye-line was level with the clutch, meaning I could only see directly upwards out of the windscreen, patiently I waited until sky turned into tunnel - then I knew we were there.

Driving under the Mersey, he’d always say, “Ahhh, the Mersey; go in for a swim, come out smoking a cigar.”

Joe was funny, but not much for censoring. It would make your toes curl hearing some of the stuff he said about his customers. Cynical, sarcastic, anything for a laugh. Favourite spots to have a ‘Geoff Hurst’ were pointed out as proudly as John Lennon’s old house. (FYI, the top one was over by Cammell Lairds.) He made up songs too. His tuneful mantra while driving around looking for fares was, “Get your bloody hands out, minge bags!” Then I’d chime in, and he’d clip me and say, “Ay, you.” Hypocrisy was a cornerstone of parenting in the ’90s, wasn’t it?

You can’t just burn juice driving round all day, so we’d hedge our bets at the rank outside Iceland in The Swan. This was his territory and a good opportunity for Welsh Joe to show his offspring to the lads: No-Neck, Gadget, Bumbag, One-Ball, Manic, and The Man with the American Teeth. Their stories of dropping wealthy men at brothels, picking up Steve McManaman at Melwood, and chasing after ‘runners’ were an education. And they always seemed to be at war with private hire cars, these men, specifically Delta.

He knew everyone on Prescot Rd, from the fruit-and-veg girls to the bookies to what he referred to as his ‘Bingo Babes’; the Mecca letting out at half three every day was a sure thing. I don’t know if Dad used to bet, but our house was always full of those little blue betting pens that he’d handwrite dockets with. When I think about the mantelpiece in ours, I just think tiny pens, slummy kept in a beanie hat, and notes written in capital letters on the back of envelopes along the lines of: AIMOGGS, IF YOU’VE TAKEN ANY OF MY £2’S - I’LL BURST YOU! LUV DAD.

It was confusing, though, for us kids - the dichotomy. We saw Dad shine, bringing wit, charm, and flirtation to people who were otherwise fed up, eking out tips and smiles with all the charisma he could muster. The cabbies thought he was hysterical. You could even tell Barbara on the radio had picked Echo62 as her favourite. It was thrilling to watch the performance, until I became old enough to cringe. But between fares, and when he got home, he couldn’t hide how jaded he was. That tortoise shell was heavy. Unlike Jed Clampett, he was clever, a reader, but lacked the courage to leave taxiing for something with more financial security and more time for us. He dabbled with carpet cleaning and window cleaning, but nothing stuck. Behind all the jokes he was bitter, ashamed, and resentful. We all felt it deeply.

Anyway, “another day, another dollar!” The meter was on, and we had to “earn a crust!” Yes, we. I knew I was being exploited when I played co-pilot. Having a tiny mascot in the pit did wonders for tips.

Chips were normally on the cards for dinner; Dad seemed to have sussed the precise formula for avoiding waiting too long and was quite passionate on the matter. “Never, ever go in a chippy with no one waiting, ‘cause as sure as eggs is eggs, they’re only starting the fryers up when you walk in”. I remember being flung with force to the edge of the luggage bay from a sharp U’ey on realising one of his gold-standard chippies we were heading for did not have the optimum length queue. “If all else fails, head to Steve’s (they do the best curry sauce anyway).”

Life in and around the cab was a type of learning that couldn’t be obtained from school: reading people, building resilience, intuition, creative thinking, street-smartness. I always thought I’d enjoy swapping stories with that other Amy whose dad was a taxi driver, alas…

He’s gone now, mydad, Welsh Joe, Joe le Taxi, Joe Baksi, José, Jobo Nuthead (it’s a long story) So is the era of hackney cabs - almost, and slummy - most definitely. I wonder what he’d say about Ubers. Probably something quite unprintable.

—

Amy Collins operates as a kind of psychic mechanic, meticulously dismantling the engine of memory to understand how it runs. She believes that our lives strange, rattling vehicles held together by anecdotes, inside jokes and the specific, un-washable scent of old diesel. Her writing is less a story and more a diagnostic report, isolating the moments of friction, the points of failure and the small, miraculous sparks that somehow keep the whole precarious machine moving. She is currently trying to calculate the exact monetary value of ‘a clip round the ear,’ adjusted for inflation since 1993.

05/06/2025

by Jasmine Nahal

For all its faults and snags, I remain grateful for what social media has brought to my life.

It was a drizzly evening in June that Violette Records came to my unsuspecting Leamington Spa, with a La Violette Società event that I stumbled across via Instagram.

With ‘an evening of music and storytelling’, I was hooked and purchased a ticket.

I recorded in my trusty journal that I wore a black satin skirt, sleeveless knitted vest, corduroy jacket and brown Solovair boots.

With lit candles and leaflets strewn on each table, it felt familiar. With each glance I saw handshakes and hugs, as though everyone shared a common love. And yet, despite attending alone, I didn’t feel out of place. Alone but not lonely.

4 acts, with 15 minutes in between.

Ellis Murphy was first up. He speaks for more than himself. Heartfelt voice and a rich harmonica, god I’m a fool for that. Passion swam through his self-assured presence, which was exactly where it should be. With a tone sunken in a history he unraveled in front of us, he played with a vulnerability that forces you to meet him with your own.

PJ Smith or ‘Roy’ was up next. Sharing his fiction with ‘grains of truth’ intertwined. Maybe it was his Liverpool accent, maybe it was the profanity, or perhaps the images he so seamlessly conjured in our minds; we are disarmed. With a sense of connection through his cadence, our differences are long forgotten. What a refreshing and ordinary privilege to live, albeit temporarily, through the lens of real and honest people.

Emma Hughes swiftly followed. A sucker for a sad song, her yearning came across so easily, you could almost reach out and hold the heartache. Unflinching and real, she strummed swords from a time gone by. Evoking a heartache feeling that I’m all too glad to see the back of. What a treat to be moved by such honest love.

Horace Panter arrived humbly, exploring the cultural shift that was brought with The Specials. What he described as being in the ‘right place at the right time’, I deigned to be punk destiny. After sharing that he trained and worked as a teacher for a number of years, I couldn’t help but sense an energy not yet exhausted. Now strumming bass in the Dirt Road Bound, Panter struck me as a mishmash of energy and an intriguing close to the night.

Since this fateful night in June, I have been fortunate enough to learn more about Violette Records and the multitude of humanity it encompasses. I’ve visited Liverpool and frequently wished to return. I’ve seen the first hand tributes pour in after La Violette Società announced it’s closure and feel privileged to have attended even one event. I will say yes to all I can.

—

Jasmine Nahal believes that a perfectly assembled outfit is a matter of fashion and a form of emotional armour for navigating her world. Her creative process often begins with ‘a kind of sartorial archaeology,’ on the digital archives of Vinted searching for the specific textures and silhouettes that resonate with a particular memory or feeling. For her recent trip to Liverpool, she reportedly spent three days assembling the perfect combination of a second-hand suit and vintage boots, an outfit she claimed was ‘tuned to the precise frequency of the city's humble, creative spirit.’ She maintains a very detailed journal of every outfit she wears to significant events, convinced that a black satin skirt and a corduroy jacket can tell a story just as profound as any word.

The Gen Alpha Lexicography

by Maya Chen

12: 'Cap / No Cap'

Etymology: Evolved from African-American Vernacular English (AAVE), where "to cap" means to lie or exaggerate. Adopted by Gen Z and Alpha as a universal binary system for truth verification (c. 2020).

I was recently telling my son a slightly embellished, but fundamentally true, story from my youth. He listened with the patient, weary expression of a detective interrogating an unreliable witness. At the end of my tale, he looked me dead in the eye and asked, "Cap or no cap?"

And just like that, the entire, complex spectrum of human memory, subjective experience and narrative flourish was reduced to a binary choice. Was my story a certified, verifiable fact ('no cap'), or was it a fabrication ('cap')? There was no room for ‘mostly true,’ ‘true from a certain point of view,’ or ‘true in spirit.’

'Cap / No Cap' is the linguistic manifestation of a generation raised in an information ecosystem where every statement is potentially a lie. It is the logical endpoint of a world saturated with misinformation, deepfakes and performative online identities. In this environment, the default position is suspicion, and every assertion requires immediate, explicit verification.

The term's genius lies in its brutal efficiency. It bypasses the messy, nuanced business of evaluating a source's credibility or acknowledging subjective truth. It is a simple, digital toggle switch: 1 for truth, 0 for falsehood. When my daughter says, "I'm going to tidy my room, no cap," she is adding a verbal two-factor authentication to her statement, a promise that this particular declaration, unlike all her previous ones, is not a lie.

What makes it so damning is that it reveals a world where truth is no longer the assumed default. Every statement is 'cap' until proven otherwise. It's a linguistic checksum, a constant, low-level polygraph test applied to all human interaction. We used to have conversations. Now, it seems, we are just exchanging data packets that must be verified for authenticity before they can be accepted into the system. It is the sound of a generation that has learned, from bitter, first-hand experience, not to trust anything anyone says, ever.

Next time: ''Glazing' - When admiration becomes a full-time, unpaid public relations job.

—

Maya Chen views language as a series of user-unfriendly software updates for a system which she has lost the instruction manual. Her work attempts to reverse-engineer the source code before her own vocabulary is rendered completely obsolete. For Christmas this year, she is abandoning all verbal communication with her family and will instead be attempting to convey the full spectrum of festive emotion, from the quiet joy of a mince pie to the existential despair of a family board game, using only a complex system of interpretive dance and a small, hand-held bell. She describes this as ‘a necessary diagnostic test’ to determine if any uncorrupted channels of meaning still exist.

Bird’s Eye View

by Ange Woolf

You call us

Street trash

Flying rats

Spreader of germs

Not eater of worms

Or pretty of wing

And no song to sing

But you have never been shown

The love that exists before we’ve been flown

The bonds that grow from egg to flight

Whether racer or homer

Street bird or roller

Listen closely

Hear our warm coo

Hold us to your breast

And feel it too

Then let us go

Watch us soar

Camouflaged in grey

By the River Mersey

And pavement floors

The roads

See our feet half-broken

Still we do try

To get out of your way

But a few seconds more

Is all it would take

For you to slow down

We were hungry

There was cake

With you

We've lived and worked

Returned to

From who knows where

We ask nothing of you

Except for kindness

Because this city

We both can share.

—

Angela the Wolf often turns her attention to the city's avian population. She often spends her days cataloguing the specific, territorial disputes of the pigeons in Williamson Square, the melancholic monologues of the seagulls on the Albert Dock and the surprisingly intricate social hierarchies of the sparrows that congregate outside Greggs. She believes that these birds might be the city's true storytellers, their calls and squabbles seem a more honest and less self-conscious chronicle of Liverpool life than any human conversation or social feed. A future collection of poems may be written entirely in what she describes as ‘a rough translation of inner-city corvid.’

The State We’re In

by Fiona Bird

At short notice I've been handed Tom Roberts' column for a fortnight and told to write about new music. The irony is not lost on me. Tom, bless him, would have spent 700 words explaining why he didn't get round to it, then recommended a book about someone who once met a musician in 1987. I'll try to be more direct, though I can't promise much.

The truth is, independent music in 2025 exists in a state of permanent schizophrenia. On one hand, we've never had more access to obscure brilliance. On the other, we're drowning in it. The algorithm has replaced the A&R man, and it turns out the algorithm is both more democratic and more catastrophically stupid.

Take Claire Rousay's sentiment, released last year. She's been making ambient music out of the detritus of daily life - text messages, air conditioning hum, footsteps - and turning it into something genuinely affecting. It's the sort of record that makes you sit very still and wonder if you've just experienced art or had a small breakdown. Rousay's been doing this for years, quietly building a body of work that treats the mundane as sacred, and she's still operating at the margins, still scraping together tour money, still considered too weird for the mainstream and too accessible for the experimental purists.

Or Ana Roxanne, whose work hovers somewhere between ambient, new age, and something that doesn't have a name yet. ~~~ came out a few years back on Leaving Records, all processed voice and synthesizer drift, and it's the sort of thing that recalibrates your nervous system. She's trans, Filipina-American and making music that's both deeply personal and cosmically detached. You'd think that combination of identity and artistry would get more attention, but mostly she plays to small rooms of people who already know.

This is the best bit: there's extraordinary work happening in corners you'd never think to look. Nídia, a Lisbon-based producer, has been quietly revolutionising kuduro and tarraxo, making dance music that's both aggressively physical and strangely tender. Her releases on Príncipe Discos are essential if you care about electronic music that doesn't sound like everything else, but you'd never know it from the coverage. She's been at it for over a decade. Still criminally underheard.

The problems, though, are structural and possibly insurmountable.

First, there's the sheer volume. Everyone can release music now, and everyone has. The slush pile has become infinite. Quality control has been outsourced to playlist curators with the aesthetic sensibility of a baked potato. Rachika Nayar's Heaven Come Crashing came out in 2022 - guitar music that sounds like Kevin Shields locked in an anxiety spiral, beautiful and overwhelming in equal measure. It got lumped onto ambient playlists next to spa music and binaural beats for focus. I assume whoever made those decisions has never actually listened to it, or understands that not all quiet music is designed to help you concentrate on spreadsheets.

Second, nobody gets paid. Rousay, Roxanne, Nayar, Nídia - none of them are making proper money from streaming. They're touring or teaching or doing commissions, cobbling together an existence from multiple income streams because Spotify royalties are an insult dressed up as a business model. You can have critical acclaim, a devoted following, and still need to drive seven hours to play a venue that holds eighty people.

Third, the infrastructure for discovery has collapsed. Record shops are either gone or have become heritage sites for men in their fifties buying reissues of things they already own. Music journalism is dead or on life support, kept alive by people writing for free because they love it, which is noble and also deeply depressing. PR companies charge independent artists thousands for campaigns that result in one playlist add and a write-up on a blog read by eleven people, three of whom are bots.

And yet. And yet. There's something quietly thrilling about stumbling across Giant Claw's recent work - Keith Rankin, making maximalist electronic music that sounds like the internet having a panic attack, all dizzying edits and sugar-rush energy. Or Ulla Straus, whose ambient work is so delicate it barely registers as music at all, just suggestions of melody and field recordings that drift past like half-remembered dreams. She's based between Minnesota and Berlin, releasing on tiny labels, and making some of the most quietly radical music around.

The state of new music, then, is this: brilliant and broken. We have the tools to make and distribute anything, but no agreed way to find it, fund it or sustain it. The artists are out there, working in obscurity or near-obscurity, making things that matter. They're just doing it for nobody, or nearly nobody, which might be the most punk thing left.

Tom would probably say I've missed the point entirely, that I should be talking about a podcast or a book about someone who knew someone. But he's not here, and I've got 800 words to fill. The music's out there. Whether anyone's listening is another question entirely.

—

I've been told I need to write a bio. Apparently people need to know who's been taking up space in Tom's column, though I can't imagine why it matters. I'm Fiona Bird, which isn't the name my mother gave me but it's the one I use for this sort of thing. Played bass in a band in the nineties that achieved a perfect state of obscurity - we released one seven-inch on a label that folded three months later. Very pure, very unrewarding.

Spent years working in a record shop in Camden that's now a Pret. Currently live in Margate because London became financially untenable and everywhere else seemed actively hostile. I have three rescue cats who are all deeply damaged, which probably says more about me than I'd like to admit.

I write liner notes for reissue labels when they remember I exist, and occasionally get asked to fill in for people like Tom when they've wandered off to contemplate the philosophical implications of a book they're halfway through. I own approximately two thousand records I never play and maintain a Discogs wishlist that exists purely as a form of self-torture.

I've been threatening to write a book about post-punk since 2018. It hasn't happened. It probably won't. I have two degrees, neither of which prepared me for a life of explaining to my accountant why I earned £347 from freelance writing last year.

I still think music matters, which makes me either admirably stubborn or clinically delusional. The jury's out. This bio was meant to be 100 words. Apparently I can't even get that right.

Where You Going Now?

Jeff Young

Indulge yourself with a hardback copy of Jeff's latest brilliant book Wild Twin :

https://www.littletoller.co.uk/shop/books/little-toller/wild-twin-by-jeff-young/

Pete Paphides

Listen to Pete’s bi-weekly Soho Radio show on Mondays 6-8pm : https://sohoradio.com/profile/pete-paphides/

Treat yourself to a record from Pete’s magnificent Needle Mythology label : https://needlemythology.com/

The Just Joans: https://thejustjoans.bandcamp.com/

Eimear Kavanagh

Tom Powell

John Canning Yates

Enter The Dragon, Exit Johnny Yates : https://johncanningyates.com/

Angie Woolf

Woolf Angie:

https://www.facebook.com/Awordslingingwoolf/

Violette Records

Keeping us in popping candy since 2013 :

https://www.violetterecords.com/store

Science & Magic

Back issues :

https://www.violetterecords.com/science-and-magic