Science & Magic | 2

In 1966, anthropologist Edmund Carpenter travelled to Papua New Guinea to study a remote tribe who had never encountered photography. When he first showed them Polaroids of themselves, they reacted with terror, covering their eyes, running away. They believed he had stolen their souls.

What fascinated Carpenter wasn't their fear, but what happened next. Within days, these same villagers were posing eagerly, arranging their features, adjusting their expressions. This transition reveals how we exist at the threshold between measurement and mystery, between what can be explained and what can only be felt. And it's at this intersection that our new newsletter, Science & Magic, aspires to call home.

The contributors to these pages are fellow travellers in this territory of blurred boundaries. Within these pages, you'll find Jeff Young's continued exploration of his memories through places in Liverpool, Ange Woolf's poetry of public transport and fleeting human connections, Risha Alimchandani's musical insights, Tom Roberts' cartography of cultural curiosities, and John Canning Yates' nocturnal deconstruction of the West Coast. Eimear philosophically explores hope and surrender. Each navigating this threshold between analysis and wonder.

For my part, I've been revisiting Cotton Mather's overlooked masterpiece Kontiki, an album that arrived from the future and landed in the wrong past. And Sally Williams files her report from the recent La Violette Società 56 in Leamington Spa.

What binds all of this mix isn't an ideology but a shared understanding that culture isn't something that just happens to us, it's something we have to collectively create and sustain through acts of attention, curiosity and intent. We're all amateur anthropologists now, whether we acknowledge it or not, documenting and interpreting the strange rituals of our contemporary lives.

If you, like us, find yourself drawn to the shadows between categories where the boundaries blur and definitions become gloriously unreliable, then you've likely found your tribe. We may not have Polaroids to steal your soul, but we promise to treat whatever these pages bring with the reverence it deserves.

With precision and wonder,

Matt

Ten Questions

with Risha Alimchandani

From her base in Manchester, Risha Alimchandani plays trombone for the band Tigers and Flies. They're currently in that strange, charged space between a record being finished and the world getting to hear it. Their new album, Smashing Scene, is coming soon on Violette Records.

Before it arrives, we invited Risha to take a short break from the final mixes to answer ten of our questions, offering a glimpse into the sounds and memories that shape her world.

● What music makes you feel at home when you're not?

If I Am Only My Thoughts by Loving always makes me feel calm and safe.

● What's your favourite sound that isn't music?

I like crackly noises - the sizzle of frying eggs, a crackling fire, crunchy leaves. They all seem to evoke a cosy mood!

● If you could time-travel to witness one musical moment in history, when/where would you go?

I would love to go back in time to Classical Athens to see the original production of The Bacchae by Euripides, which included lots of singing and dancing, a lot of which is now lost to us.

● What's the last album or song that made you stop whatever you were doing and just listen?

Simba by Antonio Neves - have a listen, no explanation needed!

● What music did your parents play that you initially rejected but later embraced?

I think it took me a while to enjoy the Indian classical music that my mum loves. Now I love it too - my whole family and I are obsessed with Nitin Sawhney, who fuses Indian classical music with flamenco, jazz, hip hop, and more!

● Who’s the person who gives you the best music tips today?

My boyfriend, a jazz trumpet player, and I spend a lot of our time talking about and sharing music. We have recently been enjoying Universo Normal by Lucia Fumero and all the wonderful gigs at the Manchester Jazz Festival.

● Which person most shaped your musical taste before you turned 18, and what specific record or gig did they introduce you to that changed everything?

I listened to a lot of 70s/80s rock with my dad growing up. He took me to see the Australian Pink Floyd show when I was young. Amazing and terrifying!!

● What song became the anthem of your first teenage friendship group, played endlessly during that one unforgettable summer?

'Being So Normal' by Peach Pit. I really associate this album with my close childhood friend - and we're still close to this day.

● What's your favourite song that is from a soundtrack to a film?

I love the recurring calypso band in Paddington, especially London is the place for me.

● What album would be most likely to trigger something and fire your brain and bring you out of a coma?

Gilbertos Samba by Gilberto Gil. I listened to this album on repeat when I was 18 and I still feel like I know it inside out.

Magnetic North

by Jeff Young

2 : The Water Tower

The water tower was one of my childhood phantoms. On Sunday walks to visit my grandparents in Grey Rock Street I was frightened of its face as it loomed over the rooftops, watching me, sometimes friendly, oftentimes malevolent. So many ruins of buildings seemed to be stone cold dead on those Everton streets, but the water tower was a tormented soul. It breathed. I thought of it as an old man like my grandfather, but an old man made of stone - perhaps an old man who didn’t know he’d passed away. It was an old man’s ghost...

Five years old, I’m walking to Nana and Grandad’s house in Grey Rock Street and the ghost is watching. I look up at the dark interiors of its eye sockets, the pigeons nesting in its skull. What must it be like to be a ghost with birds inside your eyes? In my grandparent’s parlour, clouded in hearth-smoke, I make a crayon drawing of an old man who is a building full of birds.

I am always looking for ghosts. From childhood onwards I have believed - or chosen to believe - that a building can be a ghost as much as a grandfather or a dog. The water tower was not just a haunted place, it was a place that haunts small boys. Even today when I visit it, I find it difficult to look into its eyes. Places long demolished, people long since passed away are still there, somehow, in the weather, in the shadow, in the light. Darknesses and broken buildings, darknesses and broken grandparents, darknesses and memories in the water tower’s eyes.

I see my five-year-old self, in the dark, walking home, the moon following us, the water tower watching us as we move slowly through the night. Here, in the present moment, I watch the child I used to be. I become him. My hand is still in my father’s hand, in this place, forever. And I’m no longer frightened of the ghost.

— Jeff Young, 10 June 2025

—

Jeff Young, author of the remarkable Ghost Town, maps Liverpool's hidden geographies with precision, poetry and just enough melancholy to keep it honest. Longlisted for the 2022 Portico Prize, his memoir was praised for its "plangent beauty" and "sonorous, lyrical" prose — phrases that, frankly, still don’t quite do it justice. That one of our greatest living writers has agreed to write for us feels implausible and entirely inevitable. A playwright, essayist and former lecturer at Liverpool John Moores University, he has a knack for unearthing the mythic in the mundane. Each fortnight, he’ll lead us through a Liverpool both recognisable and uncanny, reimagined through his singular eye. His new memoir Wild Twin is available now - haunting, sharp and quietly devastating.

Shadow Songs

by John Canning Yates

There is a period in time, somewhere between the last television being switched off and the first bird announcing the dawn, when songs behave differently. They shed their polish, forget their arrangements and reveal skeletal structures. In these quiet hours John Canning Yates sits at his piano and communes with these musical apparitions.

Most nights, I find myself at the piano in the quiet hours, writing, or quite often, playing songs I feel drawn to - ones I want to live inside. Sometimes, just listening isn’t enough.

Usually, it’s a private ritual. But I thought I’d begin sharing a few here on Violette’s new newsletter, Science and Magic. These aren’t polished performances - just loose late-night versions, as they come. A kind of musical sleep-talking.

This week’s song: 'A Day in the Life of a Tree' by The Beach Boys.

It’s an odd song, full of reflection, quiet decay, and isolation, but strangely beautiful. Brian Wilson becomes the weathered worn out tree ruined by pollution. Whether he’s mourning the planet or it’s a metaphor for his own unraveling at the time, who can say, but the song speaks an undeniable truth.

It opens a great trilogy that closes the Surf’s Up album: despair in the Tree, acceptance in '’Til I Die', and finally, something like transcendence in the closer 'Surf’s Up'. It’s a gentle, aching arc I keep coming back to.

More soon, from the shadows,

—JCY

—

John Canning Yates first appeared on the public record around 2005 with his critically acclaimed band Ella Guru, before retreating into a twenty-year period of meticulous private study and songwriting that culminated in his recent solo album The Quiet Portraits. He is rumoured to maintain a private card catalogue of chords, cross-referenced not by key but by the specific type of longing they evoke. His Shadow Songs series for Science & Magic is a rare public glimpse into this private work, the act of dismantling and understanding music in its most elemental, nocturnal state.

Travelling Light

by Ange Woolf

The collective consciousness rolls by on its wheels

Inhabitants talking or eating their meals

Students, locals and classic bohemia

Gazing from windows

Scrolling through media

Workers and carers

Mothers and lovers

Sharing the journey

Looking out for each other

Giving up seats

Picking up toys

Precious belongings of the girls and the boys

A dog climbs aboard

We smile as a whole

The unspoken contract

With love as its goal

Smile and be smiled at

That's how we fly

Accept that some won't

But don't assume why

Made harsh by life's sharpness

They have to save face

But given the chance

Most have good grace

The kind and brave pool where solidarity wins

And hate is for losers and fascists get binned

A city built by migrants

We pick people up

No tolerance for arrogance

We'll fill up your cup

With smiles or with ale

Kindness and change

The weird and the wonderful

The bold and the strange

As we get off the bus

'Can I squeeze past you there'

A community condensed

A collective of care.

—

Ange Woolf observes the city from architectural heights and the democratic vantage points of its public transport, where strangers briefly form impromptu communities through small acts of consideration. Her poetry documents these fleeting social contracts with precise attention to micro-interactions that together form the city's true infrastructure. Ange's work has appeared in 'Write Minds,' 'Bridge over Smithdown,' and as public installations throughout Liverpool. She maintains a collection of bus tickets annotated with single-line observations about fellow travellers, creating an alternative cartography of the city based on human connection rather than streets. Her poem 'Travelling Light' was composed during thirty eight separate bus journeys, each contributing exactly one line to the final work. Ange never once cancelled a journey due to inclement weather, believing that rain-soaked travellers reveal more of themselves than their dry counterparts.

What Shape Does Hope Take?

by Eimear Kavanagh

Somewhere between effort & surrender an invisible, formless, undefined and limitless alchemy can be found.

Love, Eimear

—

Eimear Kavanagh maintains a precise weekly ritual of walking backwards through museums, believing this reverse trajectory reveals overlooked aspects of familiar works. This practice informs her approach to these questions, examining them from their conclusion rather than their premise. Eimear's other unconventional artistic preparations includes a seasonal ritual of washing her hair in cow urine, a practice she discovered while researching ancient Indian Ayurvedic techniques that she claims 'creates necessary dissonance between conventional thinking and authentic perception.' Eimear refuses to own any black clothing, explaining that 'absence shouldn't be that convenient.'

Something Old, Something New

by Matt Lockett

I probably shouldn't admit this, but I've become that sort of person who ambushes people about obscure music. It starts with a 1:17am Spotify algorithm mishap and escalates into something approaching evangelical mania. I've been known to corner my postman for ten minutes about power-pop chord progressions. He's very polite about it, but you can see the fear in his eyes.

This is how this all began: I was lying in bed, laptop balanced on my chest, trapped in one of those late-night internet spirals that start with 'I'll just check my emails' and end with you watching YouTube videos about the history of elevator music. Suddenly, this shimmering, Beatles-esque track called 'My Before and After' started playing from my speakers. Within thirty seconds, I was frantically scrambling for headphones, convinced I'd stumbled onto some lost Beatles recording that had somehow escaped the attention of every music journalist on earth.

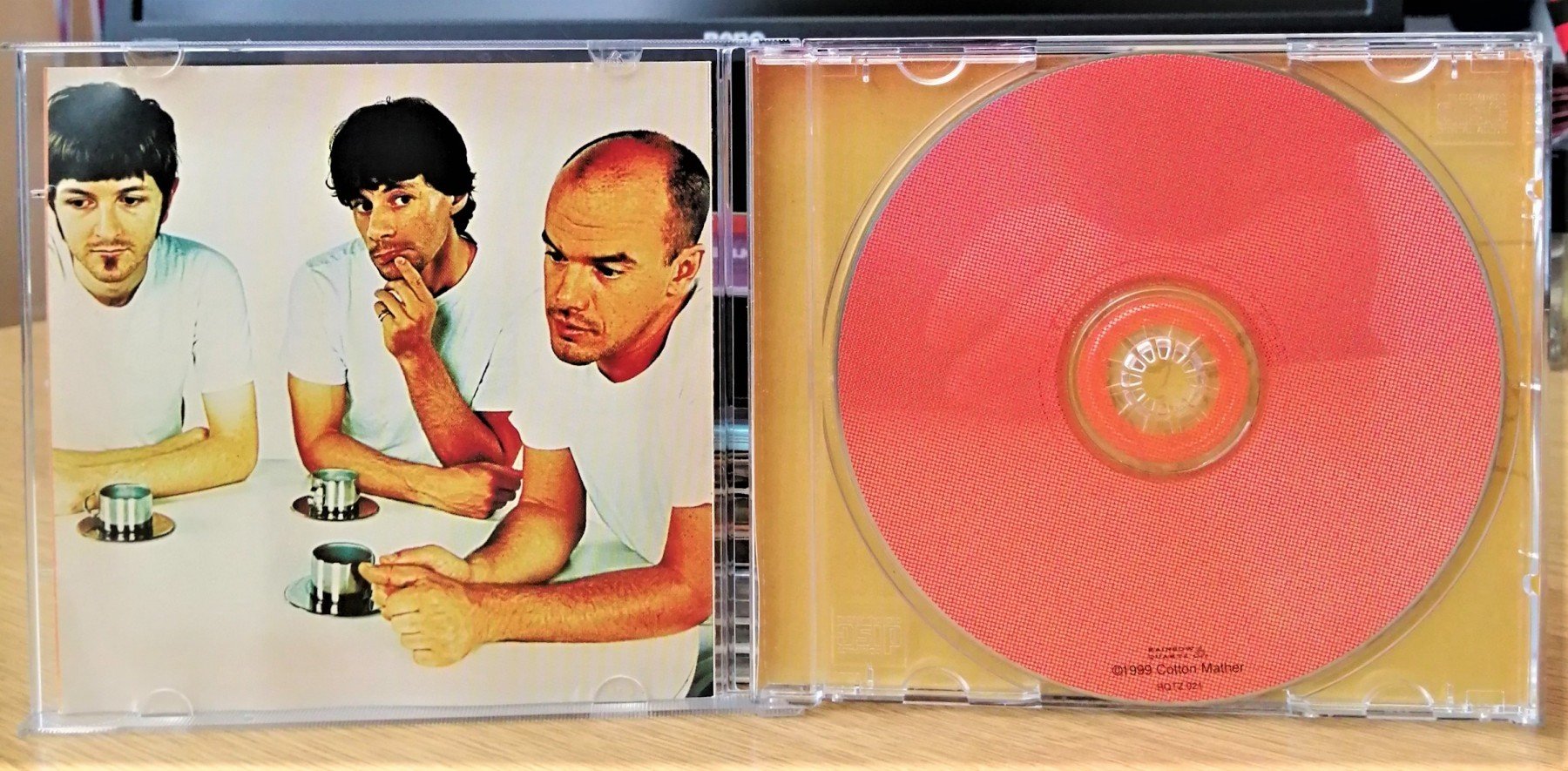

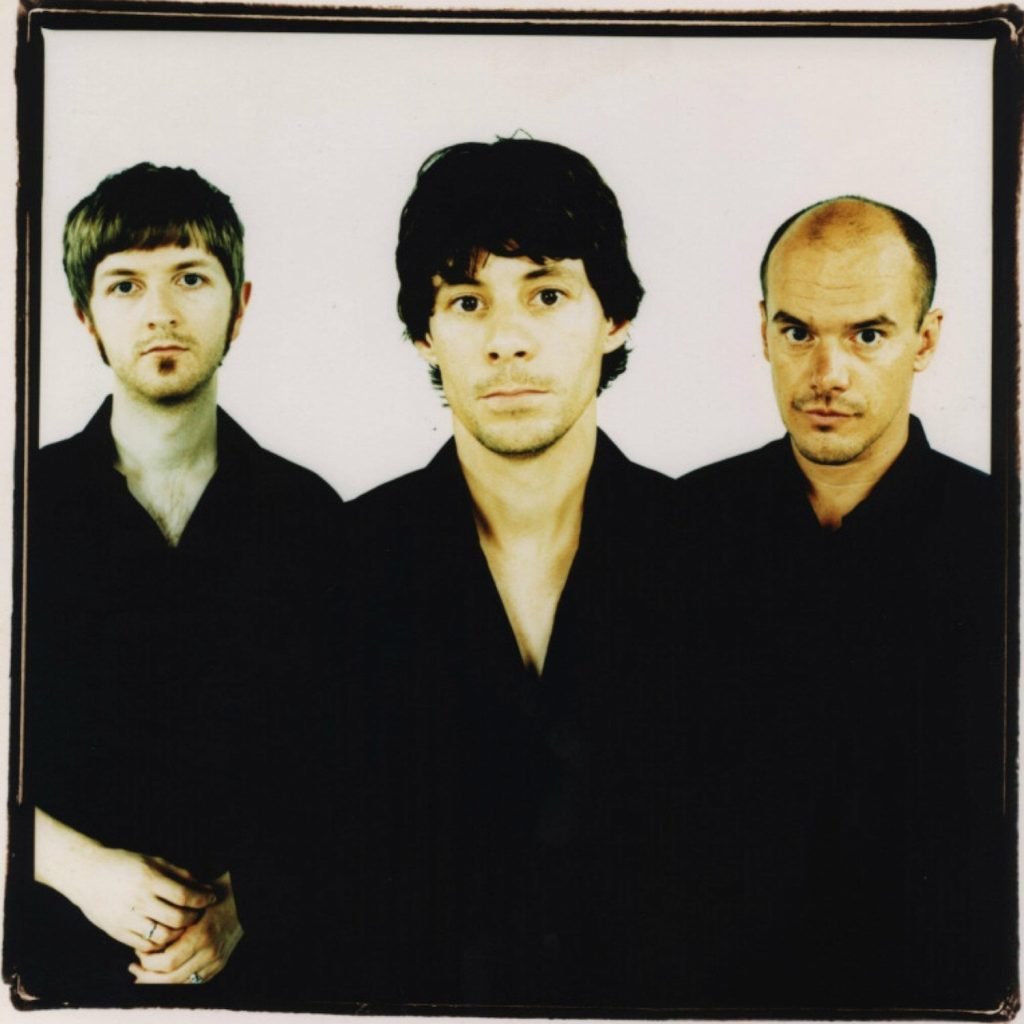

I immediately texted a friend with a screenshot: 'Have you heard of Cotton Mather?' His response arrived within minutes: 'Oh God, you've found Kontiki. Welcome to the cult.'

Cult seemed dramatic. But then I looked up the statistics. Cotton Mather's 1997 album Kontiki has just over four thousand monthly Spotify listeners. My nephew's bedroom recordings have more streams. The album peaked at number fourteen on US college radio in 1997, sold twelve thousand copies, then essentially vanished into the ether.

This bothered me more than it probably should have. Because 'My Before and After' is...well, it's extraordinary. Robert Harrison's voice soars over melodies that seem almost mathematically perfect. The production has this sparkling clarity that makes every instrument feel distinct and, at the same time, perfectly integrated. It's the sound of The Beatles if they'd had ProTools and studied composition at Berklee.

So I did what any reasonable person would do: I became completely obsessed.

I spent the next week listening to nothing but Kontiki. I couldn't help myself. Every song seemed impossibly good. 'Homefront Cameo' with its Lennon-esque demo intro tripping into something altogether more wonderful still, glistening and making me feel things I didn't know music could still make me feel. 'Spin My Wheels' builds from delicate verses to the plaintive one line chorus: 'And girl, you spin my wheels'. 'Church of Wilson' with it's chugging rhythms which explodes into an acclamation of faith that most western religions are forever struggling to buy. And 'Vegetable Row'...oh man, 'Vegetable Row'!

I started researching the band obsessively, falling down online rabbit holes and scouring obscure music forums. What I discovered was both fascinating and slightly disturbing: there really is a cult. Facebook and other online groups with thousands of members trading rare pressings and versions. Blog posts written by music critics calling it 'the best album you've never heard.' Message board threads that have been running for decades.

I found myself spending hours in these online spaces, reading detailed analyses of guitar tones and production techniques. I learned about the album's systematically unlucky timing, arriving in the late nineties when Cotton Mather was too melodic for post-grunge, too retro for electronica, too American for post-Britpop. They existed in a category of one, which obviously nobody knew how to market.

Finding Kontiki actually changes you. You become an evangelist, whether you want to or not. It's like you've been let in on some wonderful secret. And maybe that's the point. In an age of algorithmic recommendations and infinite choice, maybe the most precious thing isn't discovering something new, it's discovering something overlooked. Something that makes you feel like you've found buried treasure.

I realise I've become insufferable about this. I bought multiple CD copies as gifts. I've written lengthy emails to friends explaining why they need to listen to track four. I probably mentioned Cotton Mather in every conversation for the following month.

Discovering Kontiki wasn't just about finding a great album. it was about remembering what it feels like when music genuinely surprises you. When it reaches through your speakers and reorganises something fundamental in your chest.

So here's what I'm going to do, and I apologise in advance: I'm going to ask you to stop whatever you're doing and listen to 'My Before and After' right now. Not in the background while you check emails. Give it three minutes of actual attention.

Because I suspect you're about to join the cult whether you want to or not.

The algorithm giveth, and the algorithm taketh away. But sometimes, just sometimes, it giveth back.

—

Matt Lockett (here's me weirdly talking about myself in the third person) established Violette Records in 2013 with all the preparation of someone packing for a weekend trip only to discover they've accidentally signed up for a polar expedition. His section 'Something Old, Something New' continues its archaeological expedition through music history, documenting his remarkable ability to discover albums approximately 7 to 65 years late. Matt (me again) remains convinced that experiencing music out of its cultural context is not a failure of timeliness but a deliberate curatorial strategy. He maintains great joy in re-imagining 90's overlooked masterpieces sometime around next Thursday.

Far From Home, Perfectly At Ease

by Sally Williams

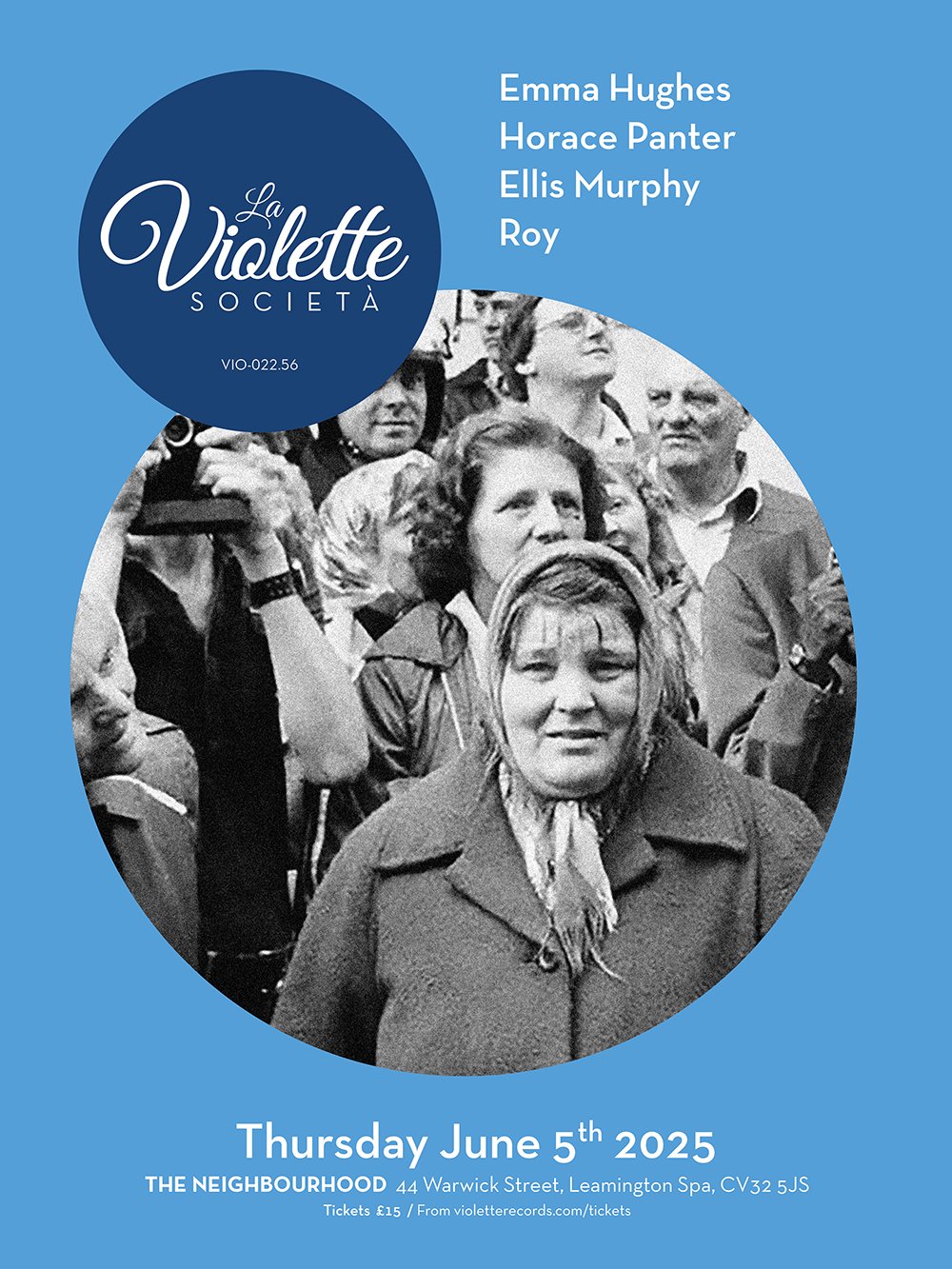

Our little cultural caravan pitched up amongst the gentle architectural pretensions of Royal Leamington Spa with its cream-coloured facades and peculiar devotion to ornamental gardens.

Sally Williams, who was there to interview Horace Panter of The Specials, captured the evening's quiet triumph perfectly.

It was a wet Thursday when the Violette revue rolled into Royal Leamington Spa - a place none of us had visited before. Ellis said the stucco Regency architecture reminded him of Brighton. I thought it looked like Trumpton with its bandstand and flower sellers.

We were here at the invitation of local lad Brendan Fenerty, who ensures his work trips to the North West coincide with the last Tuesday of every other month so he can attend his favourite cultural cabaret night. Brendan loves Violette so much he decided to take it home with him, so here we were. Violette 56, was a rare foray outside of Liverpool but was another sell out and a huge success.

Brendan, on mic duties, was a natural compere, gently explaining the Violette ethos of shutting TFU during performances to ensure everyone has a good time. Prodigiously gifted singer songwriter Ellis Murphy opened proceedings and went down a storm, as well he might, as he was returning to Liverpool the following morning to soundcheck ahead of his sold out gig in The Phil’s Music Room. Next up was PJ, aka Roy whose charismatic storytelling had the crowd delighting in his tales of violence on the 81 bus route and cosmic scousers practising their yoga on Crosby beach.

Following a short break, London based singer songwriter Emma Hughes served up a gorgeous set of her thoughtfully crafted material and then it was time for me to interview pop artist and bassist from The Specials' Horace Panter, who lived up to his nickname of Sir Horace Gentleman regaling us with anecdotes from his incredible career and answering questions from the audience.

In showbiz there’s a saying: “always leave them wanting more” and, at the end of the night, everyone was asking when Violette would be back. Maybe Matt should start thinking about franchising.

All photography by Ana Frantz

La Violette Società 57

Experience an evening where melody meets poetry, where experimental sounds blend with classic rock, and where four unique artists come together for one unmissable night at La Violette Società 57.

For one Tuesday evening in July, the usual world suspends itself as Lein Sangster, Ruins, The Keys and Jay Farley hit the stage - buy tickets.

Dagmar Zuniga

by Tom Roberts

As the world spirals toward autocracy, automation and AI, it’s refreshing to hear a unique soul expressing itself on its own terms.

Some great music gives you everything upfront. Other music takes its time. It sounds unfamiliar, even disorienting. It comes with uncertainty and divides opinion.

But something about it lingers. It intrigues. It persists.

Eventually, you put your neck on the line and say: 'I fuckin’ love this.'

Those are usually the records I hold closest to my heart.

I’m still in the honeymoon phase with Dagmar Zuniga’s latest album,in filth your mystery is kingdom / far-smile peasant in yellow music, but I think it’s going to be one of them.

Released by the good folks at The People’s Coalition of Tandy, its melodies have been haunting my waking thoughts in a way no other album has this year.

Little ear-worms keep surfacing while I go about my day - like sirens luring me to come and play on the rocks.

The album has been described as experimental lo-fi psychedelic folk, but to my ears, it defies labels in the way all the best things do.

It feels like calm, but it’s unhomely and liminal - both engaging and strangely comforting. Like the feeling you get hearing Bonnie Beecher sing 'Come Wander With Me'.

Listening to it is like peering through a veil at some sci-fi mystery cult.

It wouldn’t feel out of place as a soundtrack to a film like Valerie and Her Week of Wonders or The Colour of Pomegranates.

In fact, elements of it remind me a bit of the latest Broadcast demos LP.

There’s a similar fragility and intimacy to Sibylle Baier or Vashti Bunyan, but filtered through something more spectral - like Grouper or Joanne Robertson, using the lo-fi approach of early Smog or The Microphones.

The digital release includes an extra track that reminds me a little of an otherworldly Aldous Harding and Marlon Williams singing 'The Trees They Do Grow High'.

Raw and magical in the way only recording straight to a C90 tape on an old Tascam 424 mkII can be, in filth your mystery is kingdom captures majestic and unearthly performances, experimental tape loops, minimal synth, and nylon-string guitar in a way we rarely hear.

—

Tom Roberts is a songwriter and musician. He once tried to alphabetise his record collection by the colour of the spines. It didn’t work, strictly speaking, but he said it looked marvellous. That tells you almost everything. A songwriter of considerable discretion, formerly of Cranebuilders and now of Beatowls, he operates here like a cartographer, mapping corners of culture with the precision of a Swiss watchmaker and the heart of a romantic. As our house curator of curiosities, he does not insist. He gently recommends. And he’s usually right.

Become A Part Of This...

This newsletter is built with care and we're always looking for new voices. We welcome submissions from established artists and from those whose best work is currently known only to them.

If you're a writer, musician, visual artist, field recordist, filmmaker or photographer who feels a connection to what we're doing here, we'd love to see your work.

Drop us a line with some samples and a brief note about yourself to matt@violetterecords.com. Your work will be read, watched or listened to by our circle of 5,000 readers.