Science & Magic | 4

The architecture of a spectacular collapse reveals more than the structure ever did when it was standing. Its foundations are exposed not as stone, but as ego, its mortar not as vision, but as vanity.

The recent public unraveling of the Trump-Musk alliance felt strangely familiar to anyone who spent their formative years charting the slow, painful dissolution of great artistic partnerships. The dynamic is a classic. One, a preening, populist frontman with a gift for inflammatory words and an unshakeable belief that he is the sole conduit for truth. The other, a technically brilliant but mercurial architect of systems who, despite a desire to build the future, remains desperately in need of constant, validation in the present.

It was just like the Morrissey-Marr dynamic with significantly worse hair, a chronic absence of irony, and a complete lack of jangly, transcendent guitar lines. The public sniping, the passive-aggressive posts, the battle for the loyalty of the fan base all plays out like a less poetic, deeply unsubtle re-enactment of that story we've known for decades.

The parallels are almost too neat. What with the messianic complexes, competing claims to genius and the way personal slights become cosmic injustices. You can almost hear Morrissey's world-weary sigh of self-pity and superiority echoing through the whole affair.

So while those titans of shithousery act out their psychodramas on the world stage, we've been utterly distracted by quieter things. Welcome to the latest edition of Science & Magic.

This issue delves into spaces where time stretches and memory lingers. Jim McCulloch, a key figure in the Violette Records constellation, who shares a personal tour of his musical memories. Jeff Young takes us on a haunting journey through Liverpool's forgotten corners, where memory and myth intertwine. Daniel Williams revisits The Pale Fountains' Virgin years.

Ange Woolf turns her lens inward, exploring the shadowy dialogues we have with ourselves, while Eimear Kavanagh questions the very concept of completion

Maya Chen dissects the digital shorthand of them Gen Alphas, while I ruminate on the transcendent power of The Langley Schools Music Project. Finally Tom Roberts introduces us to Meril Wubslin's Faire Ça, and invites you to lose yourself in its world.

I hope you find something here that stays with you too.

Matt

Ten Questions

with Jim McCulloch

Navigating the terrain between chart-bothering hits with The Soup Dragons and the intricate, pastoral folk of Snowgoose requires a very specific talent. Jim McCulloch has not only made that journey, he appears to have built a quiet, comfortable home for himself in the space between. A key artist in the Violette Records constellation, Jim approaches music as a practitioner and a lifelong obsessive who just happens to also write brilliant songs.

We invited Jim to answer ten questions and unsurprisingly his responses serve as a sample of his vast internal music catalogue. It's a guided tour through a street of classics, flawed masterpieces and bands that were too good to ever be famous.

● What's your favourite sound that isn't music?

Rain on the roof, to paraphrase John Sebastian.

● What album would you press into the hands of an 18-year-old today, insisting they listen to it front-to-back right now?

Pillows and Prayers by The C86ers, if that makes sense. Just a beautiful, well cool collection of tunes that inspired, influenced and infuriated me in equal measure. When I heard this at 18, it lit the touch paper.

● If you could time-travel to witness one musical moment in history, when/where would you go?

Any night The Action played The Marquee in 1966 would work for me.

● What's the last song that made you stop whatever you were doing and just listen?

I guess that would be The Cure's 'Alone'.

● What's the first record you saved up to buy with your own money?

Special mention goes to a cassette of Elvis Presley'sThe Sun Sessions. I think it was the cartoon cover that did it. Sounding nothing like the Elvis I saw and heard on summer holiday morning TV, it was beamed down from outer space to teach us The Truth. A revelation.

● What song instantly takes you back to your school disco?

The Wild Swans' 'Revolutionary Spirit'. Not exactly the school disco it has to be said, but my mate Jim Tierney was a DJ (who dialled in records with a phone handset instead of headphones) would play this and the dance floor would go mental.

● What music did your parents play that you initially rejected but later embraced?

The Mamas and the Papas.

● Which band from Glasgow deserved to be huge but wasn't?

A band called V-Twin. Chaotic and loose art rockers channeling the Thin Wild Mercury Sound orchestrated by front man Jason McPhail, a Zelig-like character around town who was born too late - way too knowing and talented for their own good. Back for more this summer at Glasgow's Pop Festival '25!

● What's your favourite song that is from a soundtrack to a film?

'The Windmills of Your Mind'.

● What song served as the backdrop to your first genuine heartbreak, and troubles you to hear it now?

Astrid Gilberto's 'Once I Loved' - inconsolable yet insufferable. A top tier moping tune.

Magnetic North

by Jeff Young

4 : The Dylan Steps

I come up from the canal locks and once again I go to Dublin Street in search of ghosts. The city’s magical cartography - or perhaps more accurately my personal mythology - is imprinted on my imagination and this place is one of the occult compass points on my internal map. Warehouse buddleia, my dust blue dream flower, the haunting weed on blind buildings is everywhere I look: the butterfly weed is in bloom, the city rewilding itself even as it dies.

Dublin Street is empty, today there are no pilgrims, no Bob Dylan detectorists searching through the rubble for clues. Somewhere, hereabouts, 100 years ago, my grandfather would have passed, driving his horse and cart from the docks into the city. These buildings are tape recorders, unspooling sound archives of the city remembering itself. I imagine I can hear horses. Listen! I imagine I can hear children playing, a tin can kickaround in the rubble. I imagine I can hear the voice of a folk singer in the light breeze of the morning.

Bob Dylan came here, 14th of May 1966 with the photographer Barry Feinstein. In town for a concert at the Odeon on London Road, Dylan is the angel-headed hipster, half man, half insect in girl watcher shades, his wild mercury spirit captured by the camera, a Lord of Misrule jester in the ruins of the docks. The waif and stray street kids don’t know who he is, but they huddle round him anyway on the steps of the warehouse, gazing into the camera lens, dirty kneed and ragged in the wild muck and glory of their childhood. And when he drives away, they forget about the alien visitation and go back to their tin can cup final in the Dublin Street dirt. This moment is imprinted on the territory. It is memory as ghost.

Sometimes a fleeting moment is forgotten, sometimes a fleeting moment lasts forever. The camera locks the moment into eternity. The warehouse catches the memory in its bones. I sit on the steps for a minute or so, not for the first time, not for the last. I pluck a buddleia flower and press it in my notebook. Then, warehouse dust on my fingertips, ‘Tell me Mama’ in my head, I begin my walk into the city, listening to the ghosts.

— Jeff Young, 9 July 2025

—

Jeff Young, author of the remarkable Ghost Town, maps Liverpool's hidden geographies with precision, poetry and just enough melancholy to keep it honest. Longlisted for the 2022 Portico Prize, his memoir was praised for its "plangent beauty" and "sonorous, lyrical" prose — phrases that, frankly, still don’t quite do it justice. That one of our greatest living writers has agreed to write for us feels implausible and entirely inevitable. A playwright, essayist and former lecturer at Liverpool John Moores University, he has a knack for unearthing the mythic in the mundane. Each fortnight, he’ll lead us through a Liverpool both recognisable and uncanny, reimagined through his singular eye. His new memoir Wild Twin is available now - haunting, sharp and quietly devastating.

Same’s A Word I’m Not Used To: The Pale Fountains’ Complete Virgin Years

by Daniel Williams

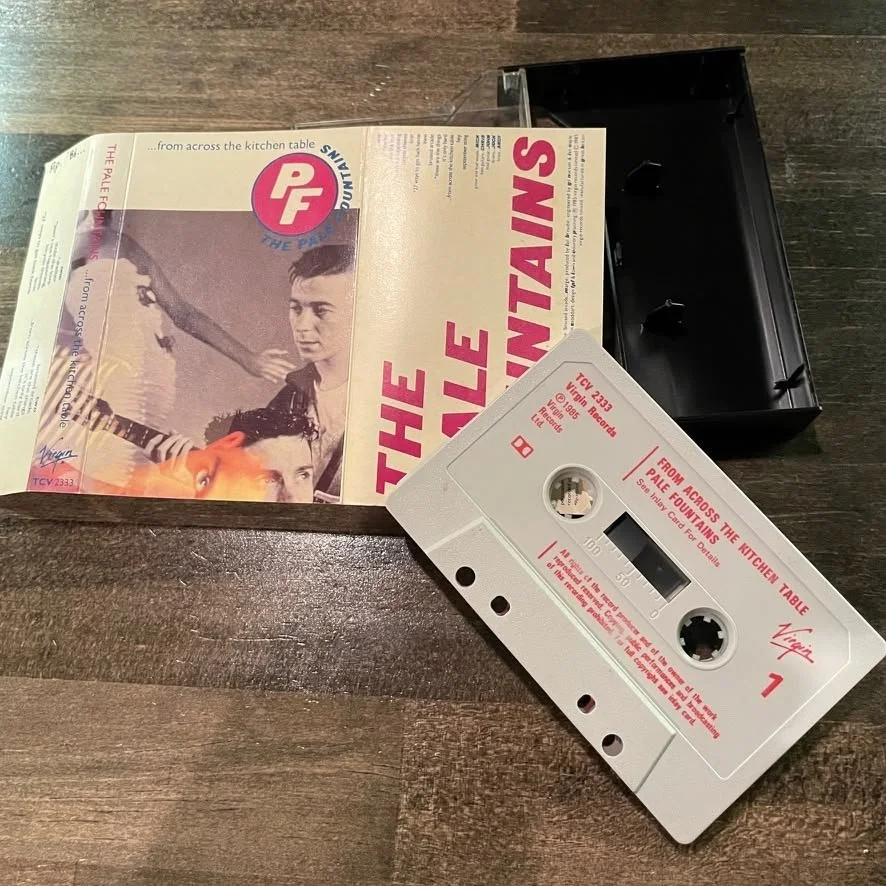

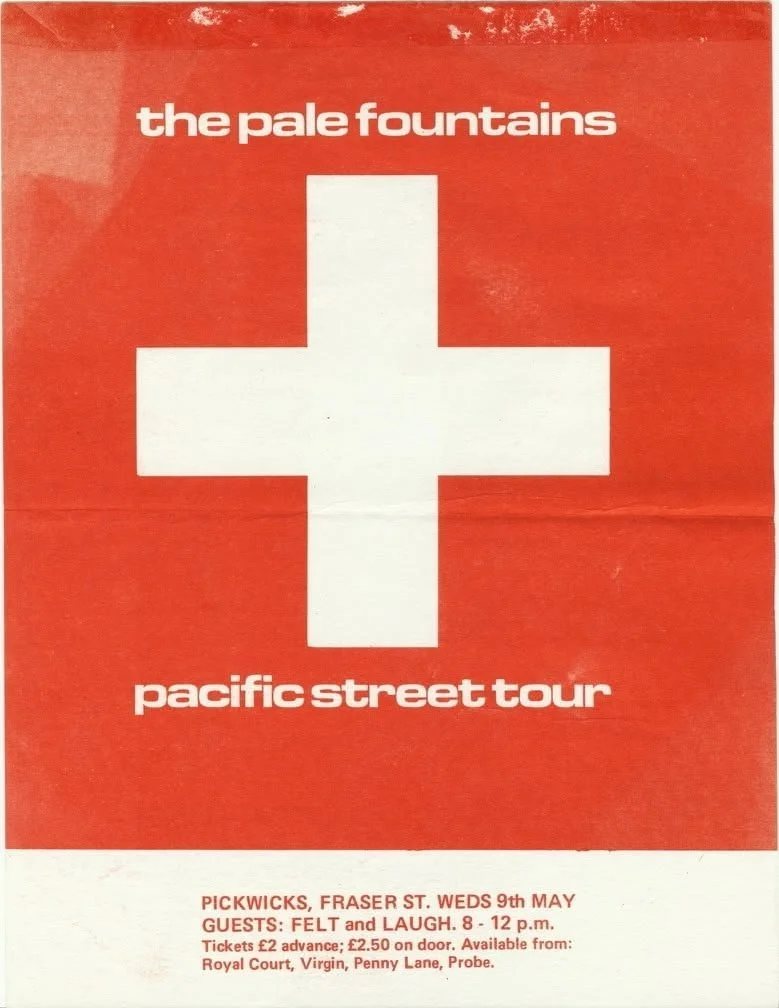

Can it really be over four decades since a school friend gave me a C90 cassette with Prefab Sprout’s debut LP, Swoon, on one side and the Pale Fountains’ Pacific Street on the other? Songs Written Out Of Necessity quickly became songs listened to out of necessity, with both albums charting the idiosyncratic melodic worlds and lyrical interiors of their chief architects. As we know, the paths then followed by the bard from the north east and the one from the north west differed substantially, with the former becoming the 'King of Rock’n’Roll', recognised for his craft with gold discs and an Ivor Novello nomination, while the latter wrote of 'Queen Matilda' and the 'Queen of All Saints' but found himself exiled from court and periodically petitioning for a return.

So, forty years on from the release of …From Across the Kitchen Table, here’s a four CD box set of the Paley’s Virgin years to stir up the seabed sediment into which our collective memories as fans of the Head brothers have likely settled. Does it go beyond Marina’s Longshot for Your Love, Crépuscule’s Something on My Mind, and such demos and live recordings as you may have downloaded from Shacknet? The answer is a fairly resounding yes. I’ll tell you for why shortly, but first, let’s look back over the first two gospels according to Michael as they were set down at the time.

There is a case to be made that Mick was never more adventurous musically than he was on the first Pale Fountains long player. The strangeness of Pacific Street – out of step at the time of release and sounding like lost treasure from a desert island now – suggests the case is a good one, which is absolutely not to say that Mick hasn’t been adventurous since, just that there is a real sense listening to the album of a vision being chased with few if any musical (or indeed financial) limits, and, for the time, an unusual set of influences – Bacharach and David, Forever Changes, and bossa nova, as well as (inevitably) the sounds from the city in which the band grew up. Ah, the fearlessness of youth, as epitomised on the pitch in the years since by Owen and Rooney. Of course, unlike a striker or a number 10, a songwriter doesn't necessarily have a limited shelf life. Over time, they can become more skilful, as Mick has, first constructing and then realising and expanding the musical framework of successive magical worlds. By the second LP, with young John come of age and his presence driving the sound towards a harder-edged guitar pop (albeit infused with Young Americans white soul), that was already happening. The songwriting and arrangements are confident and spectacular, the somewhat indeterminate romantic melodrama of Pacific Street having settled down into a kind of lyrical social realism – Ladri di Biciclette recast as a Scouse soap opera. For me, more so than the first album, ...From Across the Kitchen Table is the foundation on which everything that follows was built.

Pacific Street begins with bongos, acoustic guitar and Mick voicing lyrics in a tone barely above a whisper. Then 'Reach' is launched like a ship steaming out of dry dock, hitting the bracing waters of the Mersey for the first time. If there is occasionally the sense of vaulting ambition marginally outstripping the ability to deliver on it, somehow this only enhances the album's tender fragility, with Mick’s melancholy orchestrated almost to breaking point. Listening now, half a lifetime on, it’s also a heartbreaking evocation of youthful exuberance and teenage blues – life tumbling out of the mouth of a babe on the upbeat numbers, with the aforementioned melancholy watercolouring the ballads. Of course Mick sounds impossibly young. He was. So were we. His voice is elastic, a bird discovering the joys of flight, and, frankly, showing off with all the soaring and swooping it does.

Whereas ...From Across the Kitchen Table is is-right-positive from the clarion call of Mick shouting ‘Yeah!’ onwards. The departure of Andy Diagram and John’s newly promoted prominence similarly contributes to a more robust-sounding band. (The liner notes rightly give due credit to the brothers’ mother for giving them the space to develop into the great singer-songwriter and lead guitarist they would become.) At the same time, Mick’s lyrical style has matured; songs are just as emotive, but the emotion is positioned within storytelling and character portrayals enlivened by a poetic eye for detail: lines as inspired as ‘In a cheap hotel room, the miraculous way you bucked up when I said you were incredibly beautiful’ and ‘When I met you in the subway station, you looked as though you hadn't seen the queen's face for a while’ lodge themselves straightaway in your mind, taking up residence there for the next forty years.

So, the extras. There is the usual joy (or slog if you’d really rather only hear the perfected versions) of an expanded box set here – offcuts and cherished songs having their bones revealed in rough mixes, alternate versions or demos. Almost all of these are lovely, and some thrilling, even if the elements of Mick’s emerging songwriting genius don’t always coalesce. Very little is properly rough; in fact the quality of these mixes is technicolour-high and as fresh as if they were set down on tape yesterday. We have a bouncing 'Jock’s a Spring Bean', featuring Jock’s drums and Andy Diagram’s trumpet duelling in 'Devil Went Down To Georgia' fashion; two versions of the portmanteau 'Fight Think Love', comprised of early versions of 'Reach' (one with a meandering lyric, the other jauntily orchestrated) segueing into 'Love Situation'. In a parallel world, the orchestrated version of 'Reach' might have served as a prelude for Pacific Street, while the lead vocal-free version of 'Love Situation' would have worked well as a coda instead of 'Faithful Pillow Part 2'.

Part 2.

'Spanish Tragedy', an orchestral take on 'Beyond Friday's Field', starkly reveals the influence of Sketches of Spain as it soundtracks some real or imaginary continental screen melodrama. It’s what Weller orchestrators Hannah Peel or Jules Buckley might come up with – parallel world again – were they commissioned to write arrangements for the Michael Head Songbook at the Proms. It's wonderful to hear what might have been – an LP orchestrated to the nth degree that 'Thank You' was, but ultimately the group were right to wrest back control of Mick’s music and put the Paleys themselves closer to the heart of the record. Otherwise, 'Take a Little Shelter' might have made it onto the first LP in this earlier orchestrated soul revue version. But the band were right to hold it back, because the arrangement was far stronger by the time it came to finalising 'Shelter' for the second album.

Here's 'Hey There Fred', on its way to being 'These Are The Things'. The unfinished 'One By One' steers perilously close to Level 42 territory but from this safe vantage point serves to demonstrate what a great bass player Biffa was. Inevitably, Mr Lee gets an explicit nod, with a jammed Seven and Seven Is (recorded around the same time the Jasmine Minks would have been taping their version of the song), but with an extended slow jam ending, over which Andy Diagram blows up some bluesy improv.

The extras relating to ...From Across the Kitchen Table show are largely remixes and demos. The gold is in the latter. 'On Silver Bendix', Mick and the band are feeling their way towards 'It's Only Hard'. 'The Outsider' is an offcut which in parts reminds me of an early unreleased Red Elastic Band song, 'Full Moon', Andy Diagram’s muted trumpet in place of the latter’s clarinet. 'Summertime (It’s Only Hard)' bears little if any resemblance to the song with which it shares its parenthetical title, but Mick’s dramatic vocal and John’s lead guitar make it a highlight on this disc. Detrimentally is a skiffly, juddery juggernaut of a version of 'Stole the Love', while early takes on '27 Ways to Get Back Home', 'These Are the Things' and 'Bruised Arcade' intimate that the Paleys were developing as a unit all the time; opinions may vary about the job Ian Broudie did on Zilch, but he certainly seems to have helped perfect and fully realise the songs that make up …From Across the Kitchen Table.

So yes, the extras do make it worth investing in this box set. As so often with the Michael Head story, the what might have beens – say, a third Pale Fountains LP that may or may not have been Zilch – stand parallel and off to one side of what was. But given the way creative resilience has triumphed over adversity ever since, and what reality has therefore periodically delivered, we can't be too unhappy about the ones that got away.

— Daniel Williams

—

Daniel Williams is a writer from Hampshire. His first novel, The Edge of the Object, was published by the Half Pint Press in 2021. Recently he has been writing about the natural world for Caught by the River. Previously he worked as a music journalist and was a founding contributor to the legendary Tangents webzine.

Shadow Work

by Ange Woolf

I write only for my shadow

She, who I never saw

Before the light changed

And upon my wall

Did she cast her trace

Whilst humming these words

From a familiar place,

‘The longest way around

is the shortest way home’

I had heard it long

Before I was born

It’s like it was written

For a self that I mourned

from a time

or a place

Where I couldn't be found

And locked was this song

Buried deeply within

But she has unlocked it

Sparked life

Made it breathe

This Wild

Untameable

Wuthering storm

Untethered of shackles

At last free to roam

To fight new battles

With darkness

And to see each one

Overthrown.

—

Ange Woolf, who we all now know typically maps Liverpool's social currents from her own window seat on the 86, here turns her anthropologist's eye inward to study the passenger she knows least: herself. "Shadow Work" emerged from what she describes as her "wall watching practice" - a daily ritual of observing her own shadow cast against her flat's kitchen wall during the changing light of late afternoon. Over months of this seemingly mundane attention, Ange began to notice that her shadow seemed to move independently, to contain gestures and expressions she didn't recognise as her own. She started writing letters to this shadow self, eventually discovering that the shadow was writing back. Born and raised in Liverpool, Ange has always been drawn to the city's understanding that the longest routes often reveal the most truth. This poem suggests that our deepest battles are fought in the overlooked spaces within ourselves and that sometimes the most direct path to wholeness is learning to befriend our own darkness.

When Do You Know It's Finished?

by Eimear Kavanagh

But I don’t. Doesn’t any person, place, thing or idea leave a trace? A memory, a scent?

How about the things which live rent-free in our mind. Say, a remnant of something that is disappearing or no longer existing… Surely this must still be alive!

Call it ‘finished’, but maybe it is lingering somewhere so privately that even we ourselves don’t know that it’s there.

Love, Eimear

—

Eimear Kavanagh approaches her art as a translator of unseen forces. She begins each piece by consulting a series of hand-drawn meteorological charts that map what she terms the ''emotional pressure systems' of her immediate environment. She works from a small studio where every completed painting is immediately turned to face the wall, a practice she claims allows the work to 'continue its own private conversation without being interrupted by the artist.' She believes that the concept of 'finished' is an artistic fallacy, and that artworks, like memories, continue to evolve in unseen spaces long after we have declared them complete. Her self-portrait here is one of a series of seventy-two, each taken at the precise moment she believes she has temporarily forgotten her own name, a state she describes as 'ideally receptive.'

Everyone Wants To Dream

by Professor Yaffle

You might have already heard, but we just wanted to remind you that we've been working with Professor Yaffle on their new album Everyone Wants to Dream set for release in September.

The band has just finished something really special - eight tracks that feel deeply personal and strangely universal, all circling around Everton Brow and the particular view it offers of Liverpool and beyond. It's about getting to a certain age and looking around you, but not in the way you might expect.

We've been listening to these songs for months now, and they still reveal new layers. There's something about the way the band writes about place and memory. This is exactly the kind of record we spend years waiting for and the kind that makes all the hard work worthwhile

You know how we work here. We don't rush these things. And with Lee and the band, the process has been particularly rewarding. Some partnerships you have to work at, others just feel right from the moment you start talking.

The vinyl version is available to pre-order in our store. I'd give you a link but we are deliberately banned links in Science & Magic to keep your eyes on the prize. (PS If you click on the sleeve image above it'll take you directly to the Pre-Order page, but don't tell Matt, he'll go nuts and start muttering stuff about lazy capitalism).

The cover image is stunning - a 1979 archive photograph taken from the very spot Lee Rogers writes about. We've got more about this photo soon - what it means to the band and how the original was eventually sourced and secured.

More details to follow soon, but we wanted to keep you updated. We're genuinely excited about this one.

The Gen Alpha Lexicography

by Maya Chen

02: 'Emoji Only'

Etymology: The slow, inevitable heat death of the written word. Native usage: anyone under 20 with a phone and a data plan.

Last Tuesday, I texted my teenage daughter a sincere question: "How was your day?" The reply was not a sentence, but a brutally efficient emotional data point: 💀🫠.

It seems we are witnessing a quiet optimisation of feeling. To the digital native, words are a legacy technology - clumsy, ambiguous and ill-suited for the demands of the networked self. Why describe a feeling when you can simply transmit it? The boredom-unto-death (💀) and subsequent existential dissolution (🫠) of a double maths lesson are presented simply, like an invoice for my empathy.

The cost of this efficiency is nuance. There is no follow-up question to 💀 that isn't absurd. So 'emoji only' becomes a broadcast, not a conversation; a final, non-negotiable statement. In an online environment that incentivises definitive statements and punishes uncertainty, it makes a kind of terrible, unassailable sense. It is the language of human connection, flattened into data points more easily read by a machine than by another human being.

Next time: 'Bet' - The single-syllable grunt that has replaced 'Yes', 'Okay', and 'I suppose, if I must'.

—

Maya Chen is a digital linguist who treats emojis and memes with the same reverence others reserve for Shakespearean sonnets. Her project, The Gen Alpha Lexicography, is less a dictionary and more a cultural autopsy, dissecting am evolution of language in real time. She believes these fleeting symbols will one day be studied alongside ancient texts, even as her own children dismiss her efforts with a single, well-placed eye-roll emoji.

The Eternal Gymnasium: The Langley Schools Music Project

by Matt Lockett

I first encountered The Langley Schools Music Project in 2013, whilst procrastinating on a deadline and falling down YouTube rabbit holes. One moment watching a documentary about failed shopping centres, the next listening to a chorus of Canadian schoolchildren from 1976 singing David Bowie's 'Space Oddity' with all the earnest precision of a church hymn. I immediately rang my mate.

'You have to hear this,' I said, playing the track down the phone. 'It's the most beautiful thing I've heard all year.'

There was a pause. 'Are those... children?'

'Yes, but wait - listen to how they sing "Ground Control to Major Tom".'

What hit me wasn't the novelty of children singing pop songs, though that was certainly part of it. It was the way their voices moved in perfect unison, each word delivered with a kind of collective faith. Here was innocence not for sentimentality, but for something approaching transcendence.

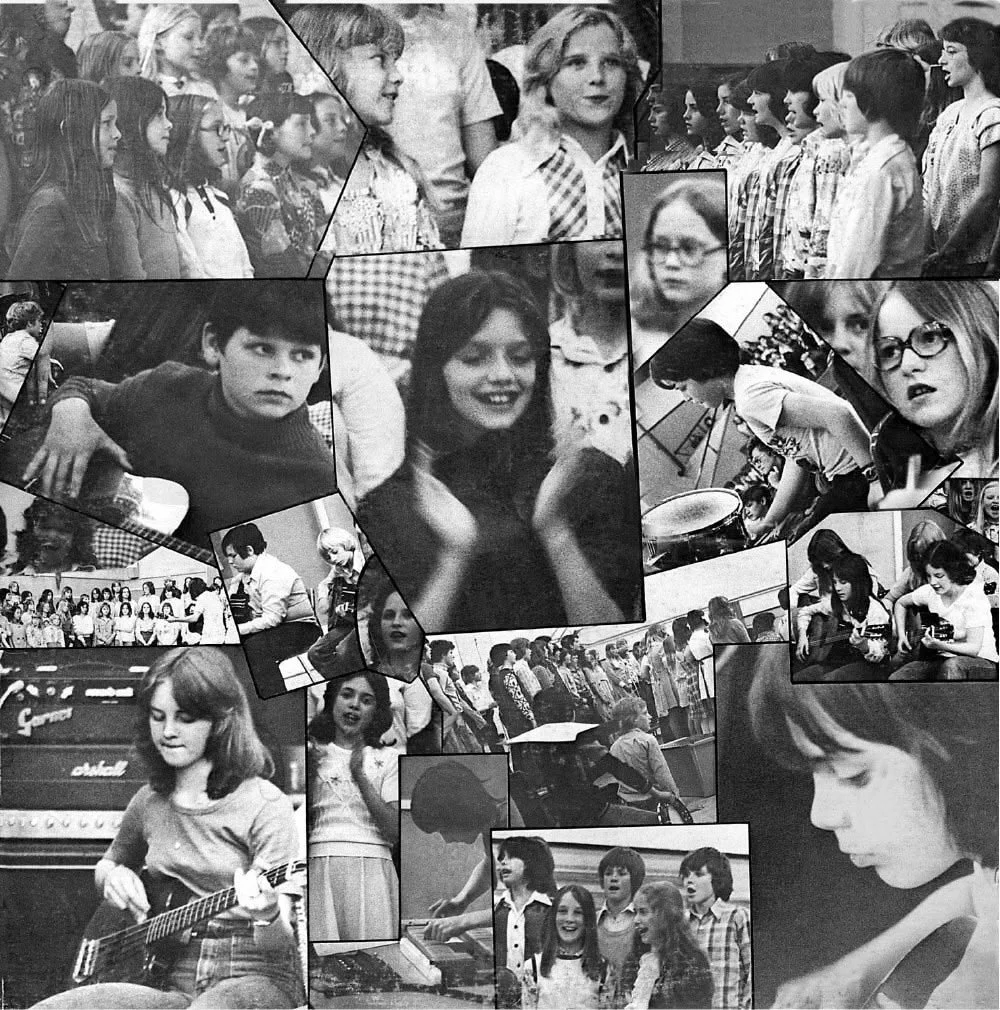

The Langley Schools Music Project emerged from the most unlikely of circumstances: a gymnasium in rural British Columbia, a reel-to-reel tape recorder, and Hans Fenger, a 27-year-old music teacher with the radical notion that children might enjoy singing something other than 'Kumbaya'. Between 1976 and 1977, Fenger recorded his students from four elementary schools performing contemporary hits by the Beach Boys, Paul McCartney, the Eagles, and yes, David Bowie. The recordings were pressed into 500 copies of two LPs, distributed locally (mainly to the parents of the kids), and then forgotten.

Until they weren't.

In 2001, the recordings were reissued as Innocence and Despair, a title that captures something existential about the project's strange magic. Here were children singing about desperados and space travel, about God only knowing and the long and winding road. Their voices were carrying these melodies they couldn't possibly understand but somehow made entirely their own. The album became what the music press likes to call a 'cult classic', which is to say it was beloved by exactly the sort of people who collect obscure records and write lengthy essays about them - ahem.

The recordings capture something we've largely lost: the power of collective voice and the particular magic that happens when children sing together without irony or self-consciousness.

Consider their version of the Beach Boys' 'God Only Knows'. Brian Wilson's original is a masterpiece of studio craft, layered with harmonies and orchestration that likely took months to perfect and nearly broke the writer. The Langley children strip it down to its essence: melody, rhythm, and the kind of communal breathing that happens when thirty voices become one. There's no vibrato, no showboating, no individual personality asserting itself above the collective. Just pure, unadorned song.

This is the sound of a kind of 'musical socialism', if you will, each voice equal, each contribution essential, the classic whole infinitely greater than the sum of its parts. It's the opposite of everything our culture now celebrates about music: the cult of the individual performer, the premium placed on technical virtuosity, the endless quest for originality. The Langley children unknowingly offered something more radical - the suggestion that music's highest purpose might be communion, not expression.

Hans Fenger understood this. In interviews, he speaks of his students not as budding performers but as a community of voices. 'It just kind of happened as it happened,' he told Global News back in 2016, with the characteristic understatement of someone who has accidentally created great art. The recordings weren't staged for fame or commercial success. They were simply the sound of children learning to sing together, captured on tape almost by accident.

In our time of manufactured child stars and competitive education, the Langley recordings feel like transmissions from a more innocent time - not innocent in the sense of naive, but innocent in the sense of pure intention. The children weren't performing for judges or audiences, but singing for the simple joy of making music together.

The hymnal quality of their performances is no accident. Fenger arranged the songs to emphasise melody over rhythm, encouraging his students to sing with the kind of sustained, communal breathing that characterises sacred music. Listen to their version of 'The Long and Winding Road' and you'll hear echoes of these voices raised in collective worship. Something secular becomes sacred through the simple act of children singing together.

There's a poignancy in hearing children sing about experiences they haven't yet had. When they perform 'Desperado', they're not channelling personal heartbreak but the idea of heartbreak. Their innocence reveals an essential emotional, stripped of the cynicism that comes with adult experience.

This is perhaps why the Langley recordings feel timeless. They capture an archetypal childhood. The moments when our worlds still seems infinitely expandable, when summer holidays stretch toward eternity and the future holds only possibility. These children sing as if they truly believe that the world will become a better place, that love will conquer all, that space travel and desperados and long and winding roads are all equally real and wonderful.

Of course, we know better now. We know that some of these children grew up to face failure and disappointment, the ordinary tragedies of adult life. We know that the world didn't become a better place, that summers end, that innocence is a luxury we can't actually afford to maintain. But for sixty-eight minutes and twenty-one tracks, The Langley Schools Music Project allows us to remember what it felt like to believe otherwise.

The children of Langley are adults now, scattered across Canada and beyond, carrying with them the memory of those afternoons in the gymnasium when they were briefly part of something larger than themselves.

Hans Fenger, now in his seventies, still lives in British Columbia. In interviews, he seems bemused by the attention his accidental masterpiece has received, pleased but not particularly surprised that people continue to find meaning in these long-ago recordings. He understands, I think, what the rest of us are still learning: that the most profound art often emerges from simple human connection, not from individual genius but from collective grace.

In the end, The Langley Schools Music Project is less about children singing pop songs than about the eternal human desire to transform the ordinary into the sacred through the simple act of raising our voices together. It's about the myth of endless summers, the belief in perpetual possibility, and the radical notion that a gymnasium full of children can, for sixty-eight minutes, contain all the hope and beauty the world has to offer.

The tape recorder captured their voices, but something more precious was preserved: the sound of a community believing in itself, the echo of childhood's infinite optimism, and the proof that sometimes the most profound art emerges from the simple decision to sing together, in unison, as if the world were listening.

—

Matt Lockett founded Violette Records in 2013, an act of uncharacteristic public-facing ambition from a man whose primary social interaction involves nodding at the postman. He is rumoured to communicate with his artists primarily through a complex system of raised eyebrows, and to have attended one of his own label's gigs disguised as a lighting technician in order to avoid conversation. His contributions to this newsletter are written late at night and delivered by a third party, ensuring that the process of sharing his profound love for music involves as little direct human contact as possible. His latest unearthing of The Langley Schools Music Project reveals his particular fondness for art that succeeds brilliantly in spite of its technical limitations - a philosophy he has, perhaps unintentionally, adopted as the guiding principle for running his own record label.

La Violette Società 57

For one Tuesday evening in July, the usual world suspends itself as Lein Sangster, Ruins, The Keys and Jay Farley hit the stage. Click the poster to buy a ticket.

Meril Wubslin - Faire Ça

by Tom Roberts

We live in a time of quick hits and fast exits.

A digital age where everything is fleeting and focused towards the next new thing.

Music has never been more available. It’s everywhere, all the time, served up in endless streams, scrolls and algorithmic suggestions.

There’s so much good stuff and I love the accessibility as much as the next person. But sometimes I want a record I can live in. A record that slips through the noise, not demanding attention but earning it.

An antidote to the churn.

Faire Ça, the fourth album from Swiss/Belgian trio Meril Wubslin, is exactly that kind of record. Released by Swiss label Les Disques Bongo Joe, it was my favourite album of 2024 and one I find myself returning to again and again.

The label describes it as having 'the intimacy of blues and folk, the experimentation of post-rock and 1960s minimalism and the heady production values of dub and hip-hop.' It’s difficult to argue with that, but Faire Ça is a record that resists easy categorisation.

Working with producer Kwake Bass, the trio stays true to their rough-edged lo-fi folk roots while developing into something harder, heavier and more rhythmically driven. Looped guitar riffs, repetitive and insistent, sit over minimalist brooding beats. It brings to mind an acoustic trip hop version of Mezzanine-era Massive Attack.

I love the vocal delivery and style. There’s a compelling contrast between Christian Garcia-Gaucher’s laconic lived-in voice and the haunting restrained presence of Valérie Niederoest. It’s like a French-language avant-folk take on Mark Lanegan and Isobel Campbell.

Faire Ça is a record that deserves more attention than it gets. The more time I spend with it, the more it opens up. It doesn’t explain itself. It doesn’t need to. It just keeps giving.

The kind of record you can live in.

—

Tom Roberts, known best for his tenures in both Cranebuilders and Beatowls, has recently abandoned what he termed the "unreliable sentimentality" of civic dowsing. He now selects his cultural artefacts for recommendation based on a complex system of bibliomancy, using an annotated 1978 Liverpool A-Z street guide. By closing his eyes and letting his finger fall on a random page, he claims the resulting street name provides a cryptic instruction for what to seek out next. A recent landing on 'Penny Lane' for instance, led him not to The Beatles, but to a privately pressed 1971 album by a retired chartered accountant which featured nine folk songs about the anxieties of decimalisation Tom has noted a statistically significant correlation between cul-de-sacs and melancholic Scandinavian cinema.

Submissions Welcome

This newsletter is built as a dialogue. We are always seeking new voices to join the conversation.

If you engage with the world through writing, music, visual art, field recording, or filmmaking and find something/anything in these pages, we would be pleased to see your work.

Please send something, along with a brief note about you, to matt@violetterecords.com. Your work will be considered with the utmost care and respect.