Science & Magic | 17

I finally watched Easy Rider last week. A mere fifty-seven years after its initial release.

I know what you're thinking. And yes, it's crazy. You see, I have this thing though, it’s like a personal moratorium I place on new releases. I deliberately wait for the heat to cool down and for the noise to subside before I go in. I like to think it gives me a clearer perspective, a kind of 'outsight' that’s impossible to get when you’re caught up in the hype of release. I get to see and hear the thing itself, without all the conversations around it. Albeit, I admit, fifty-seven years is pushing it.

Of course, I already knew the story. I’d absorbed it via some kind of cultural osmosis over the years. I knew about the drug-soaked, paranoid production, about Dennis Hopper’s notoriously volatile direction. And I was already long fascinated by the quieter details. The fact that the entire soundtrack, now considered one of the greatest of all time, was built from the editor’s personal record collection, a temporary fix that became permanent because the images and the music were so perfectly, accidentally fused. They then proceeded to spend more money licensing the songs from artists like The Byrds, Hendrix and Steppenwolf than they did on filming the movie itself.

And it was brilliant. Of course it was. Watched now, in 2026, it’s no longer a statement about a counterculture, it's actually like a ghost. A beautiful, doomed and deeply sad film about the unbearable lightness of a freedom that was never really going to last. A road movie where the destination was always going to be the end of the road. There’s no excuse for waiting this long to watch it though, I know. But seeing it now, with all its hopes and failures fossilised into myth, felt like the best way to understand it.

And so here we are again for another collection of things discovered perfectly out of sequence - artefacts existing in quiet anticipation, waiting to be found, mounted and given a place to belong.

Welcome to the latest edition.

Matt

Ten Questions

by Dominic Lewington

Dominic, aka Domino, is a musician who receives transmissions from a very specific, and entirely personal, version of 1968. From his home in Liverpool, he can, by his own admission, convince himself he is living in a London suburb from that era, just by looking out the window. His music - a beautiful, strange blend of field recordings, acid folk and psychedelia - feels like it was discovered on a forgotten reel-to-reel tape from that very time. His new album, tentatively titled Forest Hills, is reportedly finished and awaiting the right atmospheric conditions for its release.

He is a man of specific, often contradictory, tastes. He loves the perfection of The Beach Boys' Smile and the brutal chaos of Stock Car Racing. He works in a harm reduction hostel, plays in four bands on three different instruments, and dreams of one day acquiring an original copy of Ludo by Ivor Cutler. He is, by his own account, very lazy, often gets his facts wrong, and will almost certainly break your nutcracker if you invite him for Christmas.

We invited Dominic to select ten questions from our archive. His answers are a guide to a life lived in a state of beautiful, creative confusion, a world where anything is possible as long as it doesn't involve anchovies.

Domino

● What song is permanently fused to a specific place or holiday - to the point where hearing it transports you instantly?

It’s overwhelming, frankly. The feeling and vision attached to 'Sandy Babe' by Little Wings, for me, is near indescribable, but can bring me to tears sometimes, and laughter at others, but always brings me to the same smell, the same warmth from the same sun, and the same gratitude that the same love exists. It’s a very summery song, and although I can’t say I know much else by Little Wings, I know there’s lots of stuff there to discover.

● What's the first record you saved up to buy with your own money?

When I was first getting into music, I was fortunate in that my sensei was a Turkish friend who went on to study law at Cambridge University, and he took me to my first ever gig. Verve had yet to release a single, and were the support band that night, but I’ll never forget it. I immediately wanted to be like Richard Ashcroft. I waited for two weeks to buy 'All In The Mind', their debut single, in my new purple velvet flares and all that. It seems a million years ago now, but I remember every step the whole way home.

● What music did your parents play that you initially rejected but later embraced?

My mum worked in a gay club, but also used to listen to the radio lots, so I caught wind of lots of stuff from her. She liked things like Doris Day, Queen and Sylvester, all of whom I now have musical respect for, but the one that really stands out is Dave Berry. I used to laugh at her when I’d gotten into 60s stuff, because I thought I was so cool listening to Psychedelia and Freakbeat etc., whereas she liked a fey, scrawny crooner from Sheffield. Nowadays, whenever I want to think of her, I listen to Dave Berry’s album 68, and I love every moment of it.

● Who gives you the best music recommendations today?

Bernie Connor. It’s almost a cliche to say Bernie, since everyone says it, but it’s true! He has a much broader musical scope than I, but he still manages to blow me away with his knowledge. His latest recommendation was a tune that I was sure I’d know, but didn’t. It was Nino Tempo & April Stevens’ track 'Makin’ Love To Rainbow Colours', and it’s pure gold. Whatever you know about music, Bernie knows something about the same thing that you don’t.

● What song feels like it knows something about you that you never told anyone?

I’m probably going to hell for this, but let me introduce you to 'Uncle Hartington'. He’s actually a character in a song by Peter & Gordon, which is on their ‘Psychedelic cult classic’ Hot, Cold & Custard album. I seem to think the character bears an uncanny resemblance to myself, since I live on a road called Hartington, and happen to be an uncle, wear hats etc. The rest just writes itself. Really, it’s just the ridiculousness of it all that humours me.

● What's your favourite song from a film soundtrack?

I actually can’t answer this properly, but will try, just because there’s so many! Stuff that stands out includes 'Sea of Holes' by George Martin from Yellow Submarine, 'Love Montage' by Ravi Shankar from Charly, 'In The Long Run' by The Carrie Nations from Beyond The Valley of the Dolls, 'Midnight Cowboy' by John Barry, Terence Stamp’s version of Donovan’s 'Colours' in Poor Cow, and 'Driving Home' by Yo La Tengo from Old Joy. Oh, and the truly sublime Opening Credit Song by Cat's Eyes from Duke of Burgundy.

● What song or album makes you want to create?

The album 1990 by Daniel Johnston always makes me want to create. He makes it sound so easy. Simple chords, simple melodies, and simple lyrics, but the pure emotion and desperate strength in the way he puts things across is inspiring. He’s one of my favourite artists full stop. Singular, sincere, and up there with the greatest of all-time on his best days. One of the first songs I ever learned was 'True Love Will Find You', and I still perform it regularly.

● What artist do you think is criminally underappreciated?

I’ve never been able to find anyone who’s as excited by John Williams as myself, yet. Not to be confused with the film composer, this John Williams released a self-titled album on Columbia Records in 1967. His songs are a lesson in simple songwriting, structure, and how to best exploit simple arrangements. 'I Wonder Why' is one of my favourite songs of all time, and I find the album best to listen to on a Saturday morning when you’re making tea or coffee.

● What song do you associate with a major world event or news story?

The album Lie by Charles Manson, and the track 'Cease To Exist' in particular. I personally think that Charlie ended the whole free love movement. There’s some truly incredible songs on that album, ones you would expect Frank Sinatra to sing. He wanted to make a statement, but ended up confusing everyone even more.

● What new artist or band are you most excited about right now?

Maddie Ashman gives me faith in modern music and its trajectory. She’s singular in her approach, and clearly loves music, due to her obvious love of blurring the lines of theory whilst strongly adhering to it. It’s like she still believes in the search for the lost chord, and I like that. She’s so talented that success is a redundant word when one considers her career.

● What song would you send into space to represent humanity?

I’d have to choose 'If I Fell' by the Beatles. I reckon that aliens would be just as enamoured with the Beatles as the world is. I think it would send a clear message to them too… what better way to say ‘we come in peace’ than with a song politely asking for love, whilst holding a time capsule that filled the world with so much colour, optimism and creativity. Never trust anyone who says they don’t like the Beatles. That’s my motto.

Feral Wheel

Magnetic North

by Jeff Young

17 : Snowdrops

Every year, round about now, I go in search of snowdrops. It’s a moment for small encounters and close observation, a winter morning ritual, early enough for no one to notice me kneeling in mulch and mud in the scrubby patch of trees on Riverside Drive not far from my home. I’ve been here so many times, so I know exactly where to look for the first cluster every year, just on the edge of the footpath, tiny lights shining in the grey morning gloom.

Walking in the city most days I’m looking in the gutter, gleaning for rust and bottle tops, lost shopping lists, plastic sushi fish, twists of wire. Sometimes I’m looking down the alleys, shadow haunting, following hunches, internal maps. In the old days it was pubs, dock road boozers, old men’s alehouses. In the Ghost Town walks it was childhood terraced streets, teenage truant zones, canal towpaths.

Looking at buildings, ruins, derelict warehouses, ghost cinemas. Memory architecture. Always looking, slow walking, touching the materials, the sandstone and granite, the Portland stone and marble. Listening to the voices, to buildings that sound like radios and juke boxes, or tape recorders unspooling mythologies, sonic architecture, like that canal warehouse full of children’s voices...

But sometimes you just need to pause for breath and look at celandine or wild roses on the wasteland coming into bud, at the street crows swaggering down the kerb, at the glamour of magnolia on Southwood Road. And then you remember to look up at the clouds and you see a peregrine falcon battling with herring gulls over the Hope Street rooftops, or the ragged geometry of geese on the pale blue and pink evening sky.

And here I am now, kneeling in mulch and mud on a cold, grey January morning and I’m looking closely at a small choir of snowdrops. Tiny lights, the bravest of flowers, Wordsworth’s Chaste snowdrop, venturous harbinger of Spring, And pensive monitor of fleeting years! I read somewhere that the collective nouns for snowdrops are a nod, a joy, a cheer, a hope. We need the hope. I nod back at the snowdrops. And then I put my hands into ivy, fallen leaves, cigarette butts, cellophane wrapper, dirt, and I clear some space for the January flowers to breathe.

— Jeff Young, 28 January 2026

—

Jeff Young is, quite simply, a master. As the current holder of the prestigious TLS Ackerley Prize for his memoir Wild Twin, he has been rightly celebrated as one of our finest living writers. For us, he is more than that; he is the quiet, constant soul of this newsletter. Each fortnight, he takes us by the hand and leads us through a version of Liverpool that only he can see - a city of ghosts, of memory, of dreamlike portals where the mundane becomes mythic. His work is not just read, it is felt. It is a gift to be able to share his dispatches with you, and a privilege to be a small part of his extraordinary journey.

The Paphides Principle

Pete Paphides has a theory that every great song is a small, perfectly constructed argument. It might be arguing for love, for despair or simply for the necessity of dancing in the kitchen. His fortnightly song selections are a collection of these arguments, presented with the passion of a true believer. He is not a critic, he is a witness for the defence.

The Leaf Library - ‘The Reader’s Lamp’

Back in 2020, we did it for the NHS. In 2026, may I suggest that, once a week, we open our front doors and clap our hands or bang our pots and pans for another sector of essential workers? I’m talking about the dwindling stock of dogged idealists and incurable romantics who continue to make beautiful music for the even faster-dwindling stock of dogged idealists who are willing to give them money for it.

They may not save as many lives as paramedics and nurses but they do save some and vastly improve the quality of millions more. And yet, still they keep at it. These are the thoughts I’m having as I behold the skill, wisdom and exquisite taste in which The Leaf Library’s fourth album is steeped.

If you heard the previous three records, you might have a hunch about what to expect on After The Rain, Strange Seeds. At the core of The Leaf Library’s line up are ex-Saloon guitarist Matt Ashton and singer Kate Gibson; at the foundation of their music a drone which sounds like it’s being pulled down from the ether like a radio wave and latticed around Kate’s pensive rainy day ruminations. Matt’s crystalline fretwork calls to mind David Gavurin’s work with The Sundays. And on this record, the pendulous asymmetric swagger of Lewis Young’s drumming also warrants a spotlight all of its own.

When I listen to The Leaf Library, much of the appeal is the sense of stepping out of my own internal monologue and into a completely different one, with its own unique landscape of anxieties and banalities. It’s a cheap holiday – a holiday in someone else’s misery or quiet rapture or all the emotions in between – but still, a holiday nonetheless.

All of which is to say that I knew I was going to love After The Rain, Strange Seeds – but and yet, this album is a revelatory leap. I could wax wondrously about pensive chamber-folk pastorale ‘Carry A River In Your Mouth’; the swirling sonic sea mist of ‘Colour Chant’; the deep pile yearning of ‘A Ship In The Sky’; and the stunning ‘Some Circling’ – an intensifying throb of harmonic tension that explodes halfway through only for the constituent parts to scatter like mice from a burning barn. But that would be tantamount to teasing, given the wait – two months! – for the record to be released. So let’s focus on the one track that is already out there. It’s called ‘The Reader’s Lamp’ and, as it happens, it’s a perfect microcosm of the whole album, showcasing as it does the ravishing string arrangements that rise and dissipate over much of the record like smoke rings.

And so I would ask that you try and remember these words when you finally get to hear After The Rain, Strange Seeds – especially the ones at the top of this review. Think about what makes you countenance the journey to work on the rush hour train. Think about the ways you use music to feel like the lead character in a film that’s far more beautiful than the list of chores you can no longer postpone. Think about the people who go to the trouble of making that music in 2026 and are reconciled to the prospect of receiving almost nothing in return. Now grab a couple of saucepans and I’ll see you on the doorstep.

—Pete Paphides, 28 January 2026

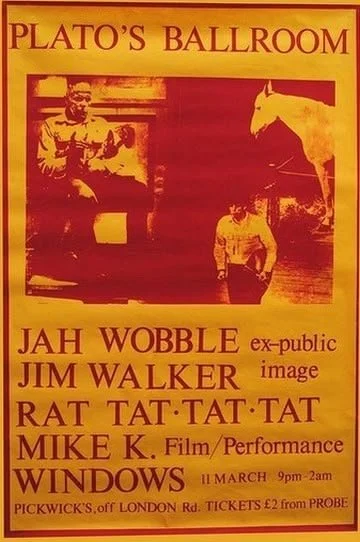

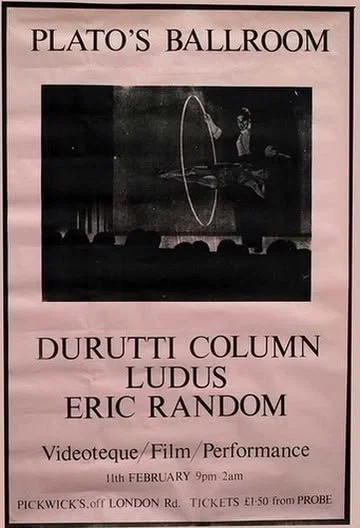

Whither Plato

by Mike Stoddart

I wandered around a patch of wasteland on the edge of Liverpool city centre, looking for a formative experience. It wasn’t there anymore. It had gone away. Perhaps it had reached the end of its useful life at some point in the intervening decades, and retired to a civilised schooner of sherry. Or maybe time had eaten away at my memory of it, until I wasn’t sure I really recognised it any more. But it was an unsettling moment, reminding me that I was at an age where disappearance hurts: the closure of a night club, the demolition of a favourite boozer, the replacement of an opulent art deco cinema with a poxy prefab Lidl, and so on. But maybe the old things we miss would have been viewed in their turn as a totem of depraved modernity every bit as ugly as the pop up Lidl. Had such an abomination been imaginable back then...

I’d gone in search of a Shangri-La for the region’s Arty Ponce community, as well as a once-vibrant night spot for people with a more traditional idea of fun. They were in the same place. Pickwick’s club was mainly the latter, but it had also presented the odd gig by the Fall, Echo and the Bunnymen and various others. In the early part of 1981, it began to host Plato’s Ballroom, an occasional medicine show which offered various tinctures of music, poetry, surrealist cinema and knife throwing, as well as some peculiar stuff. On the first night, a cold Wednesday in mid-January, New Order played one of their early gigs; projections of Bunuel films showed us dissected eyeballs and ant-oozing hand wounds; and a chap crawled out of a box in a cloud of talcum powder. There were other raised eyebrows too, especially on the faces of the regulars who had come out for a cheeky mid-week bevvy and found their club thronged with bizarros. It was all a revelatory experience for a quiet 16-year-old who had to be in school the next day, and one that was repeated pretty much every time Plato invited us to his Arty Ponce Salons over the coming months – A Certain Ratio, Fad Gadget, Cabaret Voltaire, the Fuzzy Ants and what have you. Christ knows where the money was coming from, if we had any, but nights like that taught us more than just how to spin out a drink...

But there it was, gone. Nothing. Just a patch of waste ground and a couple of disintegrating and dangerous-looking buildings. I stalked about, while the theme tune to “Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads” drifted through my head. The whole scene took me back to the dereliction which was rife in my childhood, in the early 70s; the sort of place that would attract floating aggregations of backward kids, and lumpy tramps who’d light fires with rubbish while they seared their brains with cleaning fluids. Like every space in Liverpool that couldn’t be sold to friends for “development,” today’s wasteland had become a wing-and-prayer car park. Fabulous! The Council had turned an ocean of magic into an island of revenue, by the simple medium of heras fencing. And around it stood the remains of buildings, tall and dilapidated in a manner so familiar to the slum-clearance generation. Half-collapsed walls revealed the raw insides of past lives, now exposed to let their ghosts fly free from nowhere to nowhere. Towers of buddleia shadowed overgrowing weeds, breaking out of the cracks in the walls as if sprouting through the gravestones of the city’s history. Every broken window, every broken brick, every splinter of broken wood, another strand of living history snipped and re-styled until it no longer suited its present. My formative experience hadn’t just gone, it had never been there in the first place. The building, the memory, the ghosts, flattened and exorcised along with a Xanadu of long-burnished recollection. Nothing here now but the reality, nothing to say that the diverse energies of Pickwicks had ever prevailed. Just a shit-blown car park burial ground.

...nights like that taught us that magic was real, that our youthful energy could be wired to the blue-spark electricity of the city and hooked up to its ancient, subterranean currents, the psychic and the synchronous. Those nights could walk the willing to an extended family of creatives and lunatics, writers and rioters, troubadours and tosspots. Maybe not overnight, but gradually, gradually. After that, popping out for a swift half would often feel like, well, popping out for a swift half. And while all the swift halves were delicious in their own different ways, the tastiest were the ones topped off with a glug of the occult...

Maybe the station was to blame. Pickwick’s Club was one of a number of leisure palaces that stood and fell just a few yards from Lime Street, the city’s railway terminus, the beginning and end of every flight of sex and decay. Nothing stood still around a place like that. What hope, then, for the raucous halls of cobblestone cabaret, the babels of sailors and soldiers and whores that so enchanted Kerouac, the poet of the barstool harpy? Away with them, all of them, for new developments, new bars, new drunks, lost poetry. Short walks away but a thousand miles from the Van de Graaff charge of the station’s electrified compass. From the charge that sent burn-burn-burning Jack back across the pond to spawn the Beat Generation; the charge that forced an amped-up Dylan from a grand hotel to a crumbling Everton jigger to define the age in a photo; the charge that wrapped a Ready Brek glow round a ragged-arsed teen on a January night and spirited him and his friend home to a house where rumbling underground trains rattled all the plates in the cupboard. His poor mate was terrified, God love him, although he never said if it was the sound of the world beneath him that discomforted him, or the vision of the world ahead. Or both. I wish I’d asked...

What Makes You Feel Most Unsure?

by Eimear Kavanagh

When I become untrustworthy to myself. When intuition speaks loud to me but logic wants to run the show.

Love, Eimear

—

Eimear is navigating the world with the careful hesitation of someone walking on ice that might crack at any moment. Her question for this edition -"What Makes You Feel Most Unsure?" - is one she answers daily from her studio, where certainty is treated as a suspicious intruder.

Cope’s Avenue

At the junction of Cope's Avenue and Greengates Street in Stoke-on-Trent, a former hairdresser's shop holds a vigil of emptiness.

There's something particularly melancholic about an empty hairdressers. They're places designed for transformation, for small vanities and social rituals that make ordinary life more bearable. What was once a destination that drew people here becomes a question mark in crumbling brick and flaking paint.

The building seems to wait with a patience of something that’s forgotten what it's waiting for. It’s a pause that stretches longer each year, until emptiness becomes its own kind of purpose.

Locals will remember when Mrs. Whatever ran the place, others know it only as a landmark ("turn left at the empty shop"). Junctions force decision and these vacant windows offer no guidance.

The hairdresser's closure likely happened gradually, then suddenly - with fewer customers, longer hours between appointments, the owner weighing dignity against diminishing returns until the day she simply didn't unlock the door.

On Finding Ghosts in Old Tins

The Sacred Memory Bank - Kirkby Gallery

The most profound stories are rarely written in books; they're told by the objects we leave behind. A tarnished spoon, a single orphaned die, a key that no longer fits any lock, on their own, they are just debris. But arranged with care, they become a language.

Mike Badger and our own Jeff Young are masters of this strange, beautiful grammar. Their collaborative exhibition, The Sacred Memory Bank at Kirkby Gallery, is an exercise in quiet, devotional listening to the stories that objects tell.

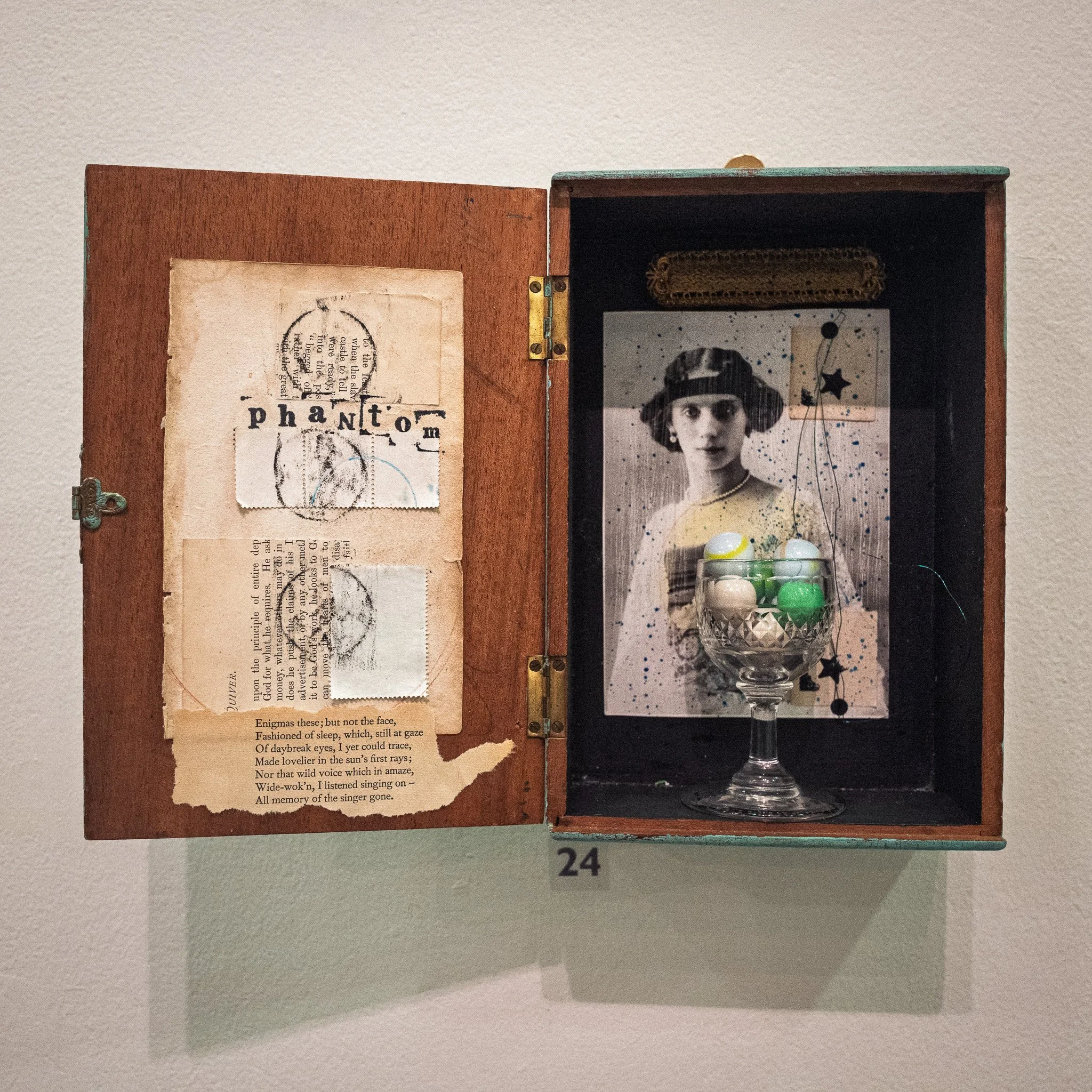

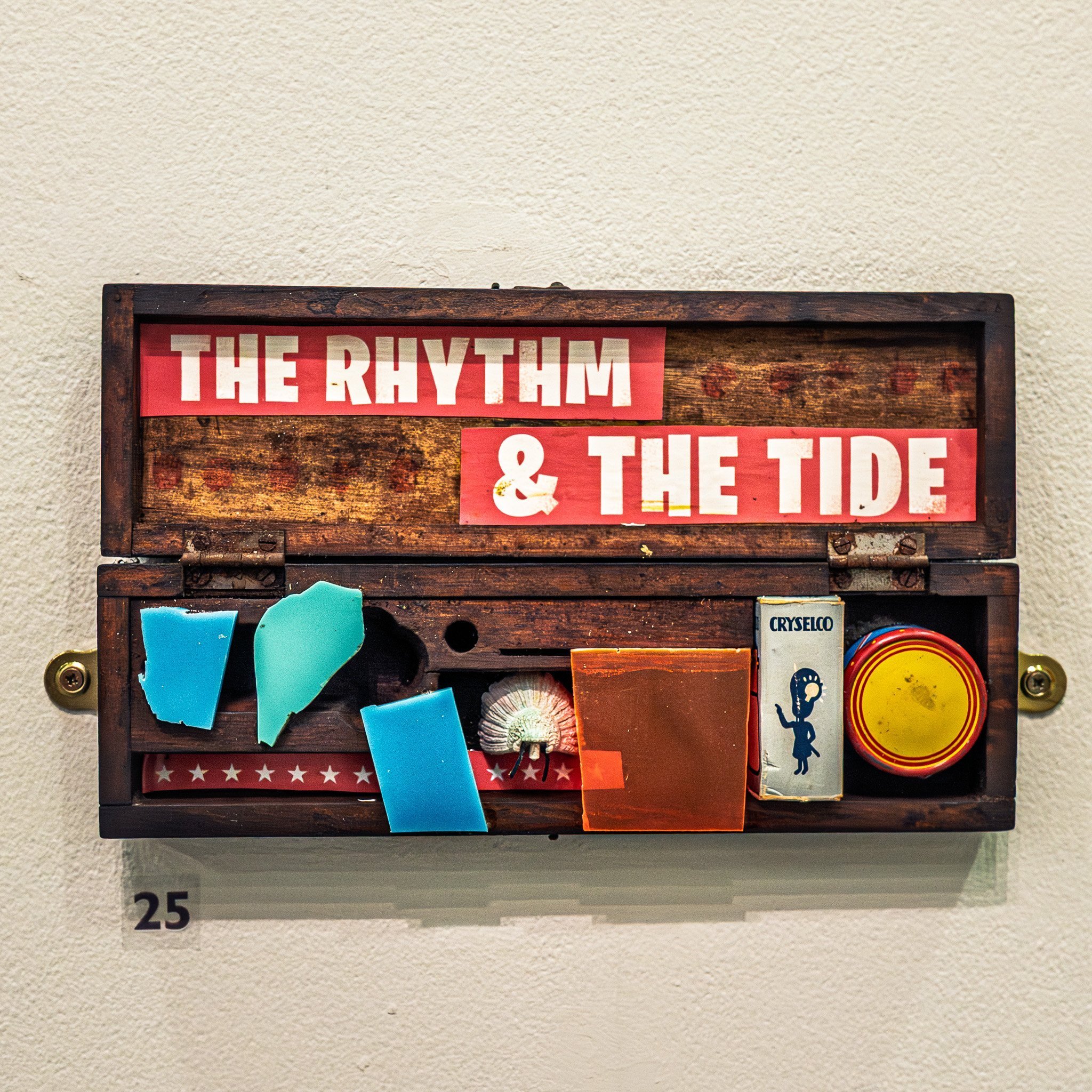

Here, the mundane becomes mythic. Jeff's father's old tobacco tins are transformed into reliquaries, housing abstract 'ghost suns' or a tiny universe of marbles and rose petals. Mike's father's shaving brush, an everyday object, is presented as something "loaded with meaning and narrative." These collections of curios are carefully constructed memory palaces, each one a silent, self-contained story.

Phantom - Jeff Young

The Rhythm & The Tide - Mike Badger

Walking through the gallery feels like sifting through the evidence of a dozen different lives. You lean in close, trying to decipher the connections. Why this specific egg whisk that looks like a "sonic spiral"? What is the story of this tiny piece of wood from Johnny Cash's fire-ravaged house? The works don’t provide answers, they just invite even more questions. They seem to act as triggers. You find yourself thinking about your own grandfather's watch (is it real gold?), about the contents of your mother's jewellery box, about the specific, irreplaceable junk that makes up a life.

What Mike and Jeff understand so brilliantly though is that these everyday items are not mundane. They are totems. Sacred objects, imbued with the emotional residue of the hands that once held them. As Jeff says of his father's collection of tiny mustard spoons, "What I like about things like this is they have the potency of people once using them, we don’t know who that person was and I find the resonance of that really beautiful."

In this world obsessed with the new, the disposable and the digitally pristine, there is something rebellious about celebrating the old, the worn and the beautifully damaged. The Sacred Memory Bank is a powerful, deeply moving reminder that our stories are not just in our heads, they are in the things we keep, the things we lose and the things we can't quite bring ourselves to throw away. It is an extraordinary exhibition. Go and see it.

The Sacred Memory Bank is on at Kirkby Gallery in Knowsley until Friday 27th March 2026 and is free to attend. More Information

The Gen Alpha Lexicography

by Maya Chen

14: 'Cook'

Etymology: Evolved from African-American Vernacular English (AAVE), specifically the phrase "let him cook," meaning to give someone space to do their thing. Expanded by Gen Z and Alpha into an all-purpose verb for creation, competence, and success (c. 2022).

I recently walked into the kitchen to find my son staring intently at a pile of Lego bricks. When I asked him what he was building, he held up a hand to silence me and said, with the gravity of a surgeon mid-operation, "Let me cook, Mum."

He was not actually preparing food. He was assembling a small, plastic spaceship. But in his mind, he was engaged in a process of high-stakes creation that required absolute focus and utter respect.

'Cook' is the new universal verb for doing anything well. You don't just write an essay; you 'cook' it. You don't just have a good idea; you are 'cooking'. To 'let someone cook' is to acknowledge their potential for genius and to give them the space to realise it. It reframes every act of creation as a kind of alchemy, a magical process where raw ingredients are transformed into something sustenance-worthy.

The term's absolute brilliance is in its democratisation of genius. It suggests that everyone has a 'kitchen' - a specific domain where they are the master chef. It elevates even the mundane act of playing a video game or choosing an outfit to the level of a some culinary art. It turns life into a series of potential Michelin-star moments.

But it also implies a pressure or expectation. You can't just participate; you have to cook. You have to produce something that is not just good, but delicious, consumable and worthy of public consumption. It is the language of a generation that sees every action as content, every thought as a recipe, and every life as a restaurant that is always, exhaustingly, open for business.

Next time: 'Rizz' - The indefinable quality that separates the main characters from the NPCs.

—

Maya Chen has now been absorbed by the culture she observes. She spent the last three days attempting to communicate with her toaster using only the lyrics to Skibidi Toilet. She has recently begun introducing herself to strangers as "The Final Boss of Ohio," a title her children have informed her is grounds for immediate emancipation.

The Old Lie

by Angie Woolf

Hunched over, the once tall strong man

Coughing like a barking dog

Wheezing like a rusted pipe on a battered van

Phlegm deposited neatly into his tissue

As he shuffled towards the self-check in screen, disinfected, still wet

Silently acknowledging the thing in the rear view

Getting closer to them all every time they met

Quiet desperation seen on every seat and stool

‘Afternoon everyone’- the regulars nod back in resignation

They had all heard him say before how hard he had tried to stop

How it was impossible since he had lost his position

After fifty years of the hardest work, lungs filled with asbestos from down the Docks

He found himself without a job and smoking kept him going

I understood him - body battered, worn and torn

I sometimes think about his story punctuated by splutters and crackling hisses

He glances at me - I hear his lungs tattered and torn

If you had heard how they’d laid him off, too old to start again - left him in financial mess

How he lost his wife after forty years - all gone - their bed, their home, the life they’d shared

Maybe you would utter less

Those oft repeated words about hard work

And how it equals success

Maybe you’d see that the many work harder than those few

That dine out on their profits whilst blaming them for their vices

And push them to work harder in order to pursue

The unattainable Myth of Meritocracy

Maybe you will push your children towards

A better life by stopping the perpetuation of the old lie

That hard work always equals rewards -

And no job is more important than your life.

—

I can’t imagine an edition of Science & Magic without one of Angie Woolf's poems. She has become the newsletter's constant, quiet heartbeat, translating the rhythms of her life into verse. Her latest poem, ‘The Old Lie,’ is a dispatch from the waiting room of late capitalism and is a beautiful portrait of dignity eroded by decades of hard labour and hollow promises. Angie believes that the most important stories are often the ones told in coughs, shuffles and silences, and she is determined to make sure they are heard.

The Chairman of Heartbreak

by Fiona Bird

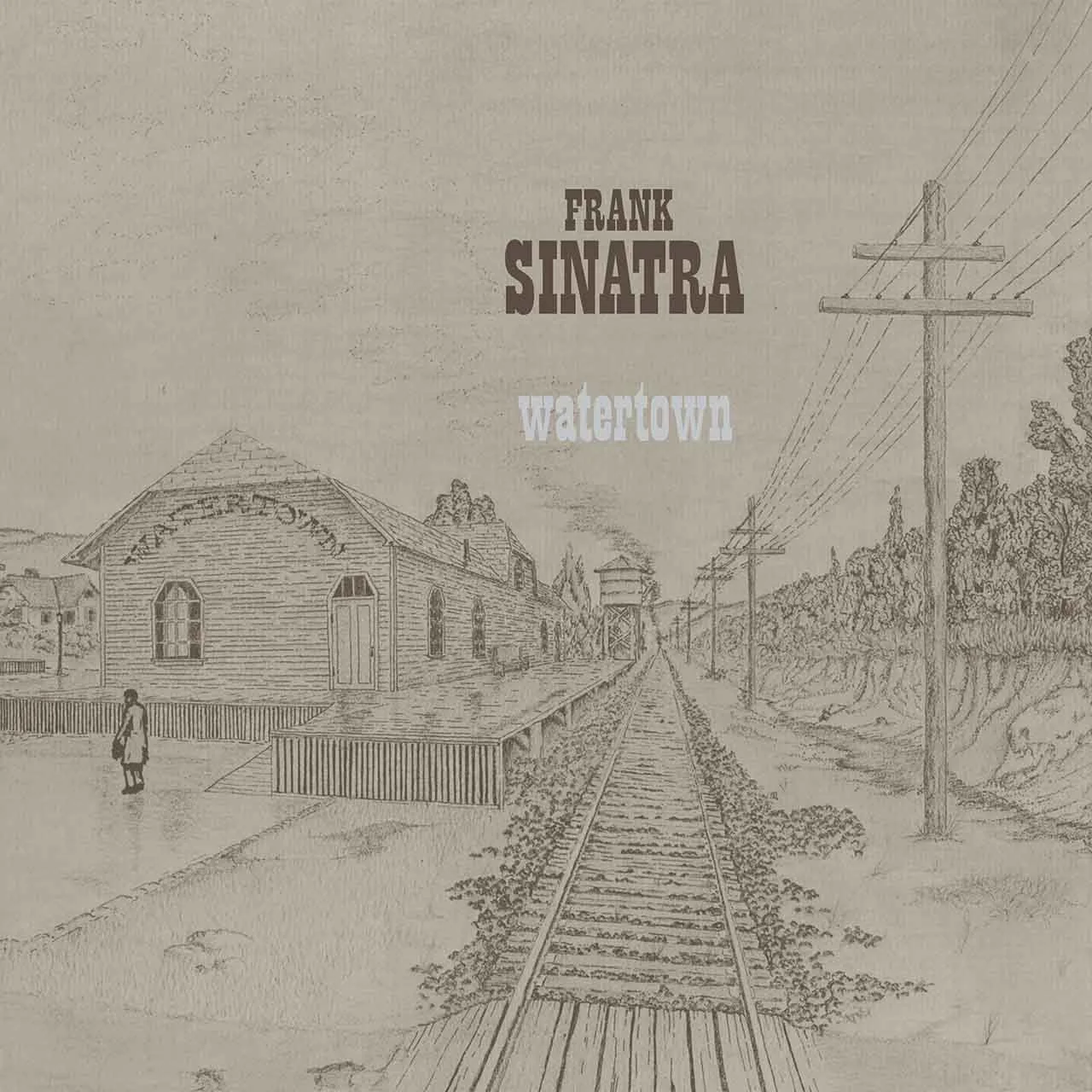

Frank Sinatra made a lot of records. Most of them sound like Frank Sinatra. Watertown sounds like a man you've never met, telling you about the worst thing that ever happened to him.

Released in 1970, it sold 30,000 copies and peaked at number 101. The Chairman of the Board, reduced to a railroad worker whose wife has left him for the city. The record was, by any commercial measure, a disaster. It was also the most honest thing Sinatra ever recorded.

The premise is simple enough to be devastating: Elizabeth has gone, left her husband and two sons in a small upstate New York town for dreams of something bigger. What follows is eleven songs of quiet, unshowy devastation. No swagger, no ring-a-ding-ding, no winking sophistication. Just a man trying to make sense of the fact that the person he thought he knew best has walked away without looking back.

Bob Gaudio and Jake Holmes wrote it as a complete narrative, which should have been Sinatra's first warning. He'd built his reputation on standards, songs that had been tested by other voices and smoothed by repetition. This was bespoke heartbreak, written specifically for him to inhabit a character - as far from his public persona as it was possible to imagine. The man who made Las Vegas cool, playing a guy who works for the Santa Fe railroad and shops at the local grocery store.

The recording process was equally alien. Sinatra always preferred live sessions, feeding off the energy of musicians and the spontaneity of the moment. Watertown was recorded as overdubs, Sinatra's voice laid over orchestral tracks that had already been committed to tape. It should have felt bloodless. Instead, it feels like someone whispering confessions in an empty house.

The songs unfold like overheard conversations. ‘Goodbye (She Quietly Says)’ captures the moment of departure over coffee shop pie, no drama, just the sort of everyday cruelty that leaves you staring at the wall for hours afterward. ‘Michael & Peter’ finds him writing letters to his estranged wife, using their sons as emotional leverage, the sort of desperate manipulation that feels shameful even as you understand it. ‘The Train’ builds to the crushing revelation that he never actually sent any of those letters. He's been conducting an entire relationship in his head.

What makes it extraordinary is Sinatra's commitment to the role. This is the man who could make ‘My Way’ sound like a victory lap, now singing about checking the mailbox every day for letters that will never come. He’s inhabiting the character completely, trading his urbane authority for something much more fragile. That voice that commanded rooms now pleads with an empty house.

The timing couldn't have been worse. 1970 was not a year for concept albums by middle-aged crooners, especially concept albums about domestic failure in rural America. Rock music was eating everything and here was Sinatra making his most adventurous, emotionally naked record just as his cultural relevance was evaporating. The critics praised its ambition. The public ignored it completely.

Which is their loss. Watertown has aged into something close to perfection, a masterclass in inhabiting someone else's grief. It's the sound of Frank Sinatra, of all people, discovering that vulnerability might be more powerful than invincibility. That sometimes the best way to sound like yourself is to become someone else entirely.

The man who never let them see him sweat made an album about falling apart. It sold nothing and meant everything. Fifty-six years later, it still sounds like the best secret he ever told.

—

Fiona Bird, who has once again stepped in to cover for Tom Roberts while he decodes the emotional significance of a particularly well-placed lampshade in a David Lynch film, brings her own rigorous, unsentimental eye to the cultural archive. She approaches music criticism as a fan and as a forensic accountant of heartbreak, tallying all the emotional cost of every failed commercial experiment. Her defence of Watertown here, is typical of her method of finding the profound in the unpopular and the genius in the disaster.