Science & Magic | 5

Every creative act is a quiet exercise in free will - a decision to notice one thing over another, to follow a thought down a strange alleyway, to pair a sound with an unexpected image. On their own, these are small, private rebellions. But when collected, these individual acts of attention begin to form a strange and beautiful map of a shared consciousness, revealing patterns and connections we never could have seen alone.

Consider for a moment, the quiet, persistent miracle of allotment gardening. In small, partitioned plots of earth, dozens of individuals exercise their own private wills - one choosing potatoes, another dahlias; one meticulously weeding, another letting nature take its course. The result is not chaos, but a complex, unintentional harmony. It's a perfect, unconventional example of how a collection of independent, personal choices can cultivate a landscape far more interesting than any centrally planned garden.

Within these pages, you will find our own collection of surprising combinations. We have a ten-question expedition into the mind of our graphic designer, Pascal Blua, revealing the punk posters and cinematic maestros that shaped his eye. Jeff Young takes us through a secret portal in a Liverpool alley, where memories and ghosts linger on wet flagstones. We present a feature-length conversation with sound artist Alice Boyd, who treats the natural world not as a backdrop, but as the main character.

Meanwhile, Angie Woolf offers a poem from the quiet republic of her own home, Eimear Kavanagh explores the beautiful torment of inherited sensitivity, and Maya Chen continues her vital lexicography of Gen Alpha slang. We also have a new single from Professor Yaffle to announce and Tom Roberts makes a compelling case for the lo-fi brilliance of Chicago band Sharp Pins.

These are the fruits of our small, partitioned plots of attention. We hope you get beautifully, irretrievably lost in here.

Matt

Ten Questions

with Pascal Blua

Pascal Blua, my co-founder, our label's eyes, spirit and soul, approaches his craft with the same meticulous attention to detail that he brings to his lifelong love affair with music. From the crackling of wood in a fireplace to the transformative power of a Devo concert, Pascal's world is one where sound and vision intertwine, each inspiring the other.

I invited Pascal to answer ten questions, offering a glimpse into the creative mind that shapes the visual identity of Violette Records. His responses reveal a tapestry of influences, from the punk energy of Jamie Reid to the iconic film credits of Saul Bass. This is a journey through a landscape where music and design meet, creating a harmony that is both deeply personal and universally resonant.

Here are his reflections.

● What's your favourite sound that isn't music?

The crackling of wood in a fireplace.

● Which person most shaped your musical taste before you turned 18, and what specific record or gig did they introduce you to that changed everything?

My best friend's sister's boyfriend was much older than us and he went to London very often. On each of his trips, he came back with his arms full of records and we spent hours listening to the bands he introduced us to. Around 1978/1979 (I was 14), I abruptly went from children's records to punk and the emerging new wave. One day, he suggested (with our parents' agreement!) that we go see a Devo concert recorded for the television show Chorus presented by Antoine de Caunes. It was my first concert and I had never seen anything, nor imagined anything so incredible. After that, nothing was the same and music took over my life.

● What's the first record you saved up to buy with your own money?

At the time, I was young and I didn't really know where to go to buy punk/new wave records. There was a record store in the town near my house but it was pretty cheesy and I couldn't find anything from the bands we were listening to. So, I asked this friend to bring me back from London my favourite record at the time, the Devo B Stiff EP which had been released on Stiff Records. When I got it, I was crazy about the record and the cover, it was my first vinyl!

● What records got you through your toughest time?

(There’s Always) Something on My Mind by the Pale Fountains, North Marine Drive by Ben Watt and Underneath The Stars, Still Waiting by Vetchinsky Settings - James Hackett and Mark Tranmer. Over the years, these records have become faithful companions, repositories of precious memories and eternal refuges sheltered from the passing of time. I know by heart the smallest details of these songs, listened to so many times. I wander through them with complicity, as if in the rooms of a childhood home. I lose myself there to better find myself.

● Which person most shaped your creative taste before you turned 18, and what specific work did they introduce you to?

I discovered graphic design with Jamie Reid and the Sex Pistols cover art, but I didn't know then that I would make it my career. I am a largely self-taught graphic designer. I quickly felt a strong attraction to typography and enrolled in a typography course. The teacher I had opened the doors (and eyes!) to graphic designers who have become my eternal idols: the Frenchman Robert Massin, the American Reid Miles of Blue Note and of course the Englishmen Peter Saville of Factory Records and Vaughan Olivier of 4AD.

● How does music influence your design process?

I listen to a lot of music, all the time, everywhere, from morning until night and even to fall asleep! I love sitting on my couch and religiously listening to a record that I let "invade" me... in those moments, I'm not there for anyone! When I work on a record cover, it's the same process. By listening to the music and the lyrics, feelings, images form in my mind and this is very often what triggers my graphic work. I look for a form of truth, of coherence through the prism of my sensitivity between music and visual. Each cover must be unique and evoke the music as best as possible.

● What's your favourite piece of design from a film?

Probably all the film credits directed by Saul Bass, of whom I am a huge fan.

● What song became the anthem of your first teenage friendship group, played endlessly during that one unforgettable summer?

'Cherchez le garçon' by the French band Taxi Girl (featuring Daniel Darc and Mirwais). For the first time, a French band had the class, attitude and music that could be compared to our English or American idols. This was well before the arrival of the magazine Les Inrockuptibles which soon became our bible and the spokesperson of a generation.

● What's the last piece of art or design that made you stop and stare?

The opera sets and costumes created by David Hockney. They are presented as part of the retrospective dedicated to him at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris in a visual and sound chapel that immerses us in the artist's mental theater. Hockney created a form of synesthesia, that is, he associated colors with sounds because he wanted us to "see the music." It's breathtaking.

● What's the last album or song that made you stop whatever you were doing and just listen?

The song "Se Perdre" by a young French duo called 'Nous étions une armée.' The name of the group immediately appealed to me, and when I discovered this title, intense with emotion, I stopped everything to listen.

Magnetic North

by Jeff Young

5 : The Portal

The alley is the secret portal into and out of the city from childhood onwards. From Exchange Station, that long-gone dark cathedral, we’d enter the labyrinth of alleys – Tempest Hey, Hackins Hey, Quakers Alley, and Leather Lane, alley of arcane mystery. I’m walking there now, through the nothingness of Moorfields, blast zone of car parks and dereliction, past the gutted Wine Lodge, looking for the unforgotten where the alleys are long gone. These days Quakers Alley is just a stretch of tarmac between empty spaces. Nothing but a street sign where there is no street, like an insult to the dead.

Leather Lane fills my heart with longing. The light shifts as I walk into the alley and the moment is unstable. This is the moment when memory falls into me. A child’s hand in a grown up’s hand – my hand, my mother’s hand. Footsteps on wet flagstones – the imprint left behind. You can fall into a memory through the rain on a wet pavement. (I once dreamed that the Lane was a flooded mineshaft, down which I descended after losing touch with my mother’s hand, down into a falling, down into forever.)

We’d look in the windows of shoe shops and glance furtively at the lingerie boutique. In the Philatelist’s shop I’d spend pocket money on beautiful stamps from Poland - stamps like paintings in a miniature art gallery, bright water colours of animals and flowers. Leather Lane contains the past forever, even in its declining nowadays...The endless mutability of an ancient city jigger. Tell me you can’t see ghosts here? Tell me you’re not travelling through time?

Later, in teenage years, the stagger-route to pub saloons and Eric’s. Scene of a drunken fight with a friend after one too many pints in Rigby’s. The promise of a kiss with a wild-eyed girl and the realisation that it would never happen. On the corner you’d once have found Pete the Papers selling newspapers and poetry mags before he went to Mathew Street to transform the city with the Liverpool School of Language, Music, Dream and Pun. O’Halligan the Dream Merchant.

Look down the alley into the last of the light, see the desire path into the shadowplay, into fragments and illusions, time suspended, overwhelmed with loss. In the shadows, when night begins to fall you can see your entire life moving before your eyes in the secret cinema of your imagination. You can fall into a memory through the rain on a wet pavement...

Remember this, hold it in your heart...

Because one day, when you’re not looking, all of it will be gone.

— Jeff Young, 23 July 2025

—

This week, Jeff Young was awarded the winner of the prestigious TLS Ackerley Prize 2025 for his memoir, Wild Twin - an achievement he celebrated with an extra pasty. This single detail tells you much of what you need to know about one of our finest living writers.

Jeff maps Liverpool's hidden geographies with a poet's eye and a playwright's ear, unearthing the mythic in the mundane spaces of a city's memory. His work is not just read; it is felt. He guides you through a Liverpool that is both recognisable and utterly uncanny, a landscape of wet flagstones and dreamlike portals where you can, as he writes, "fall into a memory through the rain on a wet pavement."

His prose, described as having a "plangent beauty," is a haunting and powerful instrument. Each fortnight, he leads us through these shadowlands of memory and place. His award-winning memoir, Wild Twin, is available now.

The Science of Sound, The Magic of Listening: A Conversation with Alice Boyd

When we first began dreaming up Science and Magic, I kept a small, private list of people I felt were already living and working in that exact space. These were the artists whose work embodied the spirit of this newsletter before it even had a name and who treated the world with both scientific curiosity and a profound sense of wonder. At the very top of that list was Alice Boyd.

As a musician, sound artist and field recordist, Alice operates in a territory between folk melody and environmental sound, between the song and the soil. Based in London, her work is built on a simple but profound premise that the arts are the difference between 'knowing knowledge and feeling knowledge.' Alice treats the natural world as the main character, not as a backdrop for human drama.

It was a genuine privilege to speak with Alice about her process, the challenge of holding both grief and hope in an era of environmental change, and the simple, radical act of paying attention —Matt Lockett

Your work blends folk, electronic music and field recordings in a really unique way. Could you tell me about your personal journey and what drew you to this specific intersection of sound?

Thank you! Growing up, I was always interested in both the environment and music. When it came to starting my career, I was considering whether to go into the environmental sector or try my luck in the arts. I started out working in an environmental charity, but soon got the itch for doing something more creative. It wasn’t until I heard Alison Tickell, CEO of climate arts organisation Julie’s Bicycle, say “the arts is the difference between knowing knowledge and feeling knowledge” that it truly clicked that I could bring them together. Today, this manifests across my work - from weaving the sounds of the natural world through my songs, through to the radio programmes and sound installations I make.

You mention Alison Tickell's distinction between "knowing knowledge and feeling knowledge." Could you describe a moment in your work where, say, a specific sound or piece of music bridged that gap for you?

My friend filmmaker Michelle Sanders and I decided to make a short film called Arctic Ice: Under the Midnight Sun. It was inspired by a report that Michelle had come across stating that we could lose Arctic Summer Sea ice in the next 10 years. One of the things that can be so challenging about talking about climate change is that it can feel distant and far away. We wanted to turn ‘ice’ into the main character - how could we make something that is non-human charismatic? So we collaborated - I made the music, she filmed and edited, and we tried to make something that hopefully makes people feel both the beauty and the fragility of this ecosystem.

Your work explores our "interconnectedness with the natural world." What does that concept mean to you personally, and how do you feel sound is able to express it?

At risk of sounding a bit woo-woo, for me this means how deeply entangled we are within nature. From the constant flux of food, water and air in our bodies, through to the trillions of bacteria cells in our bodies, through to how our choices and actions impact the world and vice versa. Even in a city, where you can feel so disconnected from nature, we are still constantly interacting with it. The idea of 'nature' being separate from us is a false binary.

You’ve spoken about the importance of listening. How did you first learn to listen to the world in this attentive way - was there a specific moment or influence that attuned your ear to the hidden sounds of your environments?

A mind-blowing moment for me was when sound artist Tom Fisher (aka Action Pyramid) showed me how to use a hydrophone for the first time. This underwater microphone allowed us to listen to the world of a humble pond. Suddenly, I was listening to sounds I never knew existed: the trilling sounds of water boatmen, the synth-like boops and beeps of the bubbles of air being released as aquatic plants photosynthesise, the munching sound tadpoles make when they eat. This was the first time I had access to a soundscape that I couldn’t hear in my day-to-day life. It made me realise the power of sound to build empathy with ecosystems we usually don’t have access to.

Can you walk us through your process of field recording? From the moment you choose a location, what are you listening for that distinguishes a simple noise from a "found sound" you can use creatively?

Any location has interesting sounds to record. I’ve found recently one of the best ways to field record is to just find a spot, sit down, hit record and see how the world unfolds around you. Sometimes unexpected things can happen if you just sit and wait, as opposed to trying to chase a certain sound. It’s also very meditative.

How it generally works though is I’ll have a specific location in mind for a project. For example, with the ‘Found Sounds’ episodes I make for Ffern’s podcast As the Season Turns, I interview someone who works with the landscape in a fascinating way. The field recordings I collect are very much informed by their practice, as well as the location they’re in. With silversmith Cara Murphy, I recorded the sounds of her making her ‘beach bowls’, hammering the silver against a coastal rock in Northern Ireland. With ecological food grower Poppy Okotcha, it was the sounds of her planting broad beans in her vegetable patch in Devon. With wood turner Darren Appiagyei, it was the sound of his lathe as he created his latest vessel in south London. It’s such a fun task gathering the sounds of someone’s world - and often the interviewees are experiencing their work through a sonic lens for the first time.

You just described the act of sitting, hitting record, and waiting for the world to unfold as "very meditative." When you are in that state of deep listening, what happens to your own sense of self? Your internal monologue quietens, you feel the boundary between 'you' and the 'environment' dissolve?

In those moments when I am field recording (particularly if I am alone), I sort of reach back into my childhood. These days, there’s so much distracting us, whether it’s our phones or our endless to do lists. Field recording gives me a chance to fully stop what I’m doing and look/listen around. Sometimes I get lost in my own thoughts, sometimes I am focussing on what I’m hearing, sometimes I am in awe of the beauty around me, sometimes I am bored. These are all things that don’t happen if I’m staring at my phone or doing work on my laptop, so for me it’s a chance to connect with the present moment. It’s encouraged me to find those moments of stillness and boredom in other places too, beyond field recording. Like not looking at my phone when I’m on a long train journey, or taking time to lie down in the grass during summer. My brain feels so much healthier if I’m actually in the world.

So once you have a field recording, how do you begin integrating it with melody and electronic textures in the studio? Is it a process of building music around the sound, or finding a sound to fit an existing musical idea?

When it comes to my music, the field recordings often inform the songwriting. For example, with my latest EP Cloud Walking, I was inspired by a trip I took to the Cairngorm Mountains in Scotland. There, I retraced the footsteps of Nan Shepherd, a nature writer whose seminal work The Living Mountain explores the landscape she loved the most. Alongside eight other women, as part of the Following Nan Project, we spent four days in the mountains, hiking to and camping in Nan’s favourite spots. Along the way, I gathered field recordings of the rivers, wildlife and mountain atmosphere. And then the EP was born - the songs following the physical and emotional journey of the trip.

You seem to perform in very unconventional spaces like botanical gardens and mountainsides. How does performing in an environment, with its own unpredictable live soundscape, change your relationship to the music and your connection with the audience?

It completely transforms it. In these sorts of settings, there are moments you just can’t repeat anywhere else. Whether it’s the ants crawling up the microphones at the Eden Project, or the wind howling into the microphone in Snowdonia. It’s more challenging, but in a lot of ways more memorable for everyone.

When someone listens to one of your soundscapes, whether it's on a record or in an installation, what do you hope they take away from the experience? What new awareness or feeling are you hoping to cultivate?

First and foremost, I hope my soundscapes and music give people a chance to stop and notice. I enjoy drawing attention to the sounds we may not usually pay attention to. Our brains are so good at blocking out unwanted sound or distracting us. As field recordist Martyn Stewart once said to me, “the microphone doesn’t discriminate”. Recorded sound can help us look at the world in new ways where we see (or hear) more of the picture.

I think music and sound also has a unique capacity to move us. Whether a sound is pleasant or not, it usually makes us feel something, which when used wisely can be a powerful thing.

In all your work documenting and interpreting soundscapes, what has been the most surprising or challenging discovery you've made about the world's sonic health?

One thing that pops up again and again is just how present we are in pretty much every ecosystem and soundscape. No matter where I am, there will be the distant (or nearby) drone of cars and planes. Last year, I made an audio documentary for BBC Radio 4 called Shifting Soundscapes, where I resist three locations around the UK that Martyn Stewart recorded in approximately 50 years ago. The difference in the soundscapes were pretty astounding, with birdsong diminishing and the human noise increasing dramatically. It’s not as black and white as saying human presence is a totally bad thing, but noise pollution is something that is negatively impacting both the health of wildlife and humans.

The project inspired my song ‘All We Are’, which explores this sense of “solastalgia”- the grief of witnessing environmental change in a place you still inhabit, or in my case, experiencing it secondhand through Martyn.

You seem to touch on two powerful and seemingly opposing forces in this "solastalgia" of environmental grief and the hope symbolised by the returning white-tailed eagle. How do you navigate holding both of these feelings - grief and hope - at the same time in your creative work?

It’s constantly changing - grief, hope, apathy. They’re all in there. It’s the eternal battle with any work about climate and the environment. How do you get people to care? For me, I think it’s important to include all of it, to show that it’s very human to feel all these emotions about something that feels so big and unwieldy.

I see you have upcoming projects with incredible organisations like Knepp Rewilding and the RSPB. What new territories or stories are you excited to explore in future collaborations?

I’m interested in still exploring the idea of Shifting Soundscapes, but also finding more stories of hope. With the RSPB, I’ve been lucky to work on a project about the return of the white-tailed eagle, the UK’s largest bird of prey. It went extinct about 250 years ago because of activities like hunting. But thanks to conservation efforts, it has now returned to our skies. It’s a real symbol of hope.

Finally, if there was one sound from the natural world you believe everyone should stop and truly listen to at least once in their life, what would it be?

I think everyone should get up for the dawn chorus in the height of spring at least once… a year (preferably!). Most of us have probably done it before by accident - perhaps still up from the night before, or on a night where we can’t sleep. But if you can wake up at 4:30am once each spring and head to a forest, park or even a garden, it’s amazing to hear the birds sing in full force. I’ve recorded the dawn chorus in a few different locations now and it’s always interesting to hear how they differ from place to place, and how in some locations the density and diversity of birdsong is so much richer.

Photographs of Alice Boyd by Caitlin Warren, Ewan Harvey, Franci Donovan-Brady, Michelle Sanders and Iain Boyd.

Alice Boyd's music and field recordings are available on all music streaming platforms, Bandcamp, her own YouTube channel and her dedicated website.

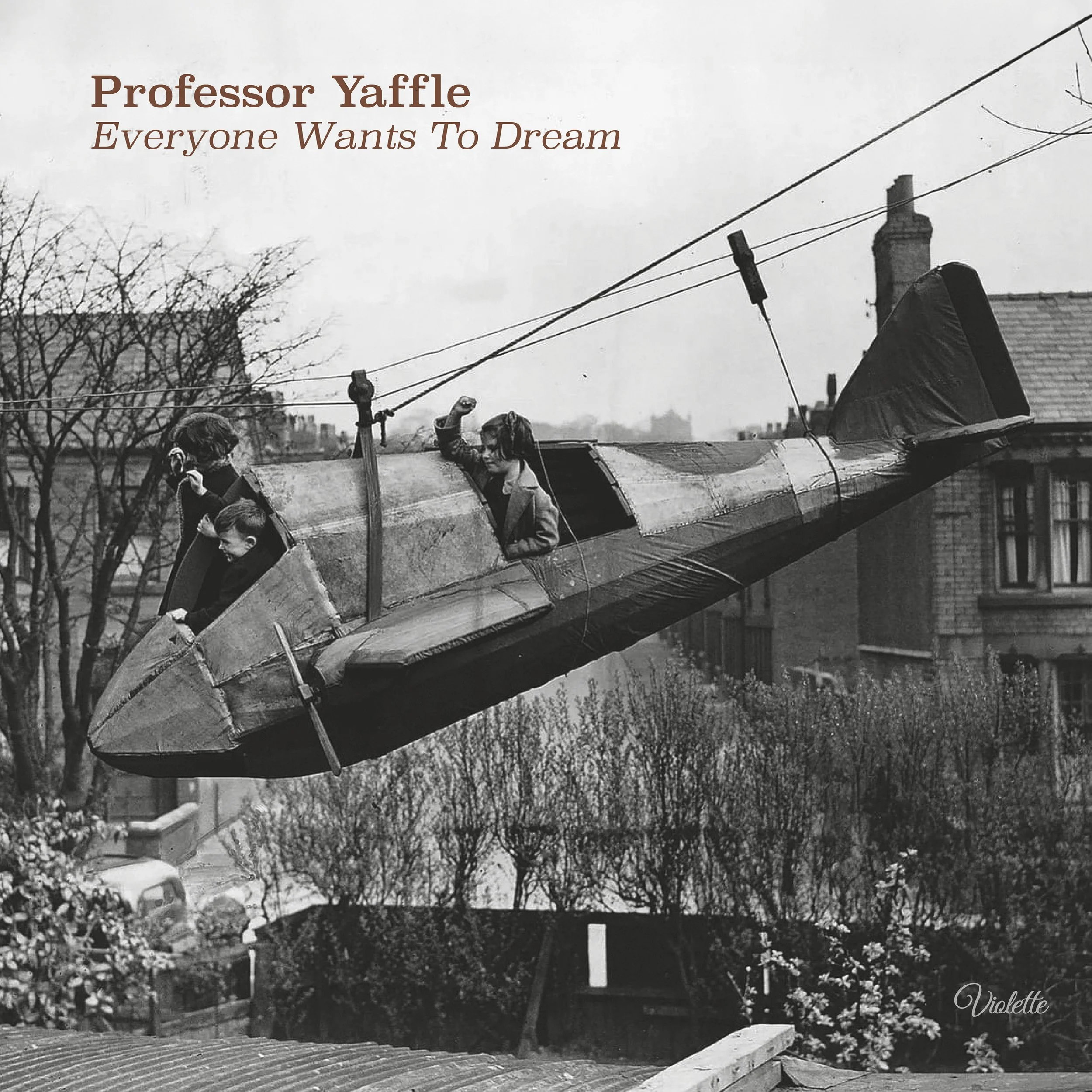

Everyone Wants To Dream

by Professor Yaffle

Professor Yaffle's title track 'Everyone Wants to Dream' is out in the world today.

This one's been living in our headphones for months now, and love it. There's something about the way Lee Rogers captures that particular feeling of finding yourself suddenly without the roadmap that's defined you for twenty-odd years. When the kids grow up and you're left wondering what comes next. We've all got our ways of dreaming our fears away, haven't we?

The full album Everyone Wants to Dream is still set for late September, but we thought you should hear this one first. It sets the tone for everything else - that mix of honesty, talent and craft that makes Professor Yaffle special.

You'll find it on all the usual places today. Give it a listen and let us know what you think. This is just the beginning.

What I've Inherited Without Consent

by Eimear Kavanagh

The Quality of Sensitivity

Is everything beautiful, feminine, and sensual

A slice of solitude, So deeply introspective and rich

The sudden illumination of inspiration

Creative bursts of unimaginable highs

A wave to ride as long as I can make it last

Right to the very end of life maybe

Dependency that knows no boundaries

A hug that landed like thunder

Isolation, a comforting indulgence

The fluff of a jumper that cut like a blade

The intensity of noise that prickles and stabs

The feelings that linger on and on

Right to the very end of life maybe

Heightened Euphoria and Stolen Dreams

Love, Eimear

—

Eimear Kavanagh's artistic practice is governed by a set of rules delivered to her in a dream by a chess grandmaster she has never met. She applies paint to canvas not with brushes, but with plastic cutlery sourced from defunct budget hotels. She insists this rigid process is necessary to create a "stable container for unstable ideas." She has no online presence and corresponds only via handwritten letters sent from a post office box in a town she has never previously visited.

The Gen Alpha Lexicography

by Maya Chen

Etymology: AAVE origins, popularised by Gen Z, inherited by Gen Alpha circa 2018-present

Gen Alpha: born after 2013, raised with AI assistants as conversation partners and tablets as pacifiers.

03: 'Bet'

I spent three months thinking my 10-year-old son had developed a gambling problem. Every time I asked him to take out the bins, he'd respond 'Bet.' When I suggested pizza for dinner: "Bet." Clean your room? "Bet." I was picturing him running an underground poker ring at primary school until my teenage nephew explained that "bet" simply means "okay" or "sure." Apparently, my child wasn't accepting wagers on household chores - he was just agreeing to do them.

'Bet' is Gen Alpha's casual confirmation, inherited from Gen Z but deployed with even less ceremony. Where adults say 'sure' or 'okay,' Gen Alpha says 'bet' - transforming gambling terminology into mundane agreement. The word carries zero actual betting energy; it's just efficient consent. My son uses it for everything: 'Homework time?' 'Bet.' 'Want some fruit?' 'Bet.' It's become his default acknowledgment, as automatic as blinking. What's fascinating is how a word rooted in risk and stakes has become the most low-stakes response possible. They've stripped all tension from "bet," turning it into verbal wallpaper. When I ask if he's ready for bed and he responds 'bet,' he's not wagering anything - he's just confirming receipt of information. They've domesticated gambling language into polite agreement, which feels appropriately absurd for a generation raised on paradox.

Next week: "Bruh" - When disappointment becomes monosyllabic.

—

Maya Chen’s children believe she is a spy. This is not, strictly speaking, inaccurate. As a cultural linguist studying Gen Alpha, her work involves the careful, covert observation of digital native communication patterns. Her ongoing project, The Gen Alpha Lexicography, is a collection of field notes from this strange, new territory, documenting linguistic mutations that appear and disappear with terrifying speed. She operates on the theory that the primary driver of language evolution is a teenager's urgent need to say something their parents cannot possibly understand. Her research methods involve listening to conversations she is not part of, decoding text chains she was never meant to see, and maintaining a stoic, analytical calm when her own children describe her life's work as "cringe."

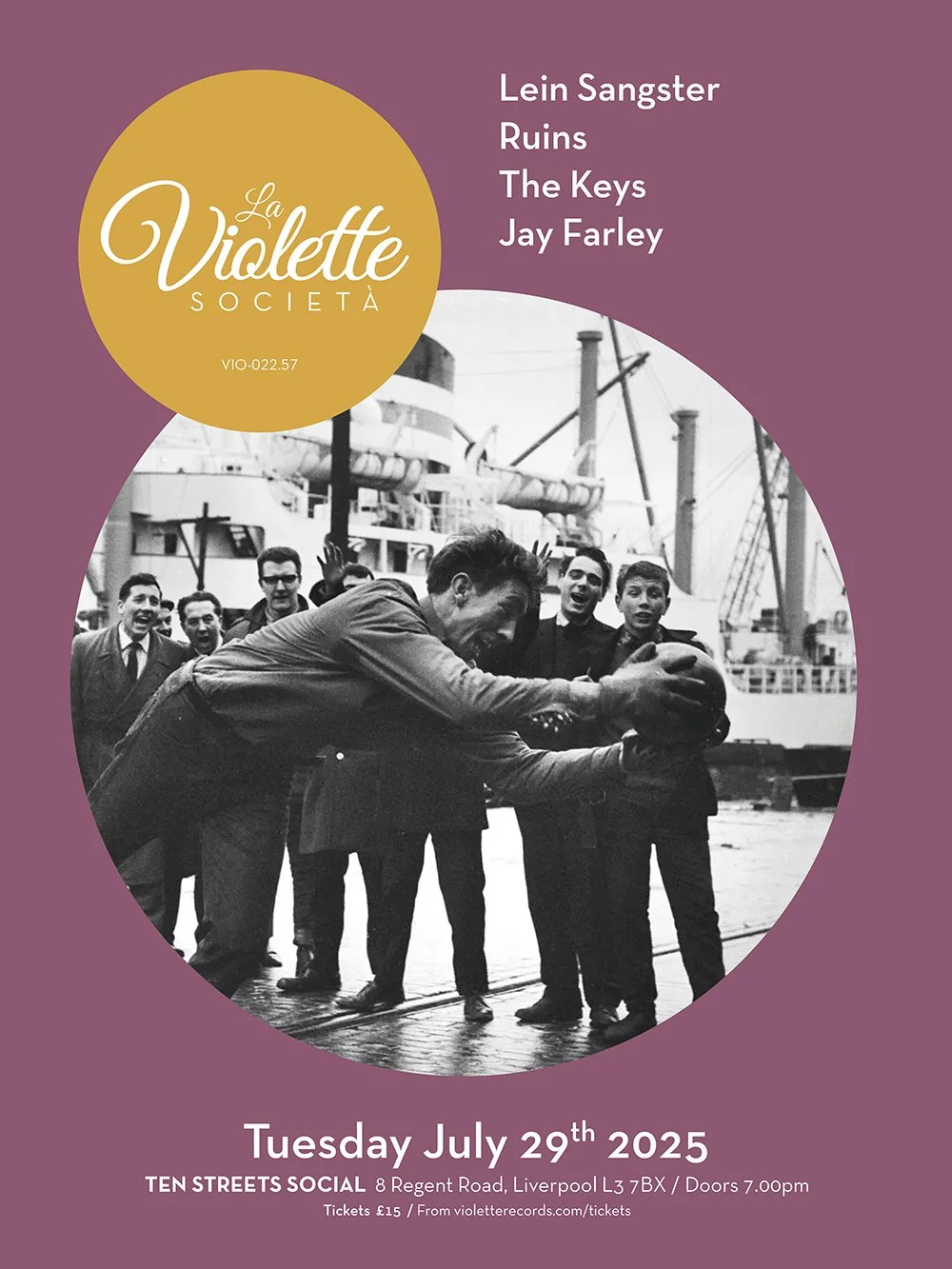

La Violette Società 57

Next Tuesday evening, the usual world suspends itself as Lein Sangster, Ruins, The Keys and Jay Farley hit the stage.

Home Is Where the Ahhh Is

by Ange Woolf

Everything I could have said

Rests in peace

Beneath my bed

Shrouded in dust

Crumbs and dirt

Endlessly slumbering

Never to be heard

'Cos words hurt like hell

When they up and take flight

All show and tell

No self-control

Fleshy face holes

Noisy and bright

But free from the could have's

And crowd shaped jeers

Is where silence descends

And truth can appear

To a heart slowing stasis

A heavenly scene

Where every day now

Is an endless stream

Of getting all of your news by memes

All thinking been put up, 'to let'

A glass of wine

A cigarette

As filth mounts up

Detritus unleashed

Woman and beast

Choose surrender

No war

Only peace.

—

Ange Woolf, pushes aside her bus timetables for a moment to reports from a more domestic space: the quiet republic of her own home. Her latest poem, 'Home Is Where the Ahhh Is', is a dispatch from a place where the clamour of unspoken words and public expectation finally gives way to a kind of dusty, detritus-filled bliss. Ange believes that true serenity is not found in tidiness or order, but in the radical act of surrender - to the mess, to the memes, to the silence. She has recently begun a project to document the specific sounds of a quiet house, from the hum of the refrigerator to the slow settling of dust on a forgotten lampshade, convinced that these are the true hymns of contentment.

Sharp Pins - Radio DDR

by Tom Roberts

I love guitar music, but it’s been a while since I was genuinely excited about guitar bands.

Maybe it’s the weather.

Or maybe everybody needs a feel-good hit of the summer.

That’s not just me, right?

But lately, I’ve been discovering bands that feel like pure joy, and in this day and age, I take my joy where I can find it.

Radio DDR, the latest record by Sharp Pins, has been a little oasis.

Think Alien Lanes-era Guided by Voices meets #1 Record-era Big Star, with a dash of Olivia Tremor Control and the spirit of Elephant 6. If you love Teenage Fanclub or The Cleaners from Venus, it might be for you. Big melodic hooks, bursts of energy, and lo-fi magic hit the right tone in my house. It’s the kind of record that makes you want to kick your leg in the air like Bob Pollard or spin a mic stand with reckless abandon... though I probably wouldn’t do either of those things.

There’s a familiarity to the sound, but Sharp Pins make it their own. They’re not copying the past, they’re channeling it, reinventing it in the way the best bands do, and the same way I just did with that previous sentence...

There’s a jangle that nods to The Byrds, but also something more youthful, garagey, and sharp-edged. That sweet spot where nostalgia meets urgency.

They’re young and inspired, driven to invent the future as if the past never existed. You know what I mean...

Kai Slater of Lifeguard fronts the band. Lifeguard also just released a great LP. He’s a man on a mission.

Yes, technically, Radio DDR was self-released last year as part of the Chicago-based HALLOGALLO fanzine, but this March the good people at K Records gave it a proper vinyl release, and in my book, that’s always cause for celebration.

Radio DDR is just genuine. Creativity, authentic excitement, and a deep love of music.

It doesn’t just sound good, it reminds you why you cared in the first place.

—

Tom Roberts, a songwriter whose records are filed in sections B and C of my collection operates on the firm belief that the most interesting art is that which is entirely comfortable in its own skin. His own songs are full of characters who have given up on pretending, and this philosophy extends to his choices. He is drawn to the quietly confident, the beautifully flawed and the things that have no interest in chasing trends - unless they're really funny. This approach was perhaps best crystallised in the spring of 2008, when, in a brief and misguided attempt to "refresh his image," he purchased a pair of beige chinos. He wore them once, for a total of four hours, during which he felt, in his own words, "like a man impersonating a better-adjusted version of himself." The chinos were never worn again. The music he shares here is the opposite of those chinos: authentic, a little worn-in and perfectly suited to its purpose.

These Buildings Are Tape Recorders, Unspooling Sound Archives of the City Remembering Itself.

1. Sam Phillips - 'I Need Love'

2. Daffo - 'Winter Hat'

3. Joshua Burnside - 'The Good Life'

4. Claudine Longet - 'Let's Spend The Night Together'

5. Peel Dream Magazine - 'Due to Advances in Modern...'

6. Charlotte Gainsbourg - 'Dandelion'

7. It's A Beautiful Day - 'White Bird'

8. Snowy Band - 'Whatever You Want'

9. Sylvie, Sam Burton - 'Sylvie'

10. Andy Shauf - 'Judy (Wilds)'

11. Stephen Fretwell - 'The Long Water'

12. Temples - 'Shelter Song'

Submissions Welcome

The pages of this newsletter are assembled, piece by piece, through a process of deliberate discovery. We believe there is an entire ecosystem of brilliant, unheralded work residing in notebooks, on hard drives and within camera rolls, waiting for the right context to emerge.

We are actively seeking submissions from writers, musicians, filmmakers, photographers, and artists whose work high-fives the spirit of this correspondence. We are particularly drawn to the quietly observed, the beautifully unconventional, and the things that don't quite fit anywhere else.

If you have something you believe belongs here, please direct a sample, along with a brief personal history, to matt@violetterecords.com. All submissions are reviewed with genuine curiosity and respect.

Where You Going Now?

Pascal Blua

Visit Pascal's beautiful design website :

https://www.bluartwork.com/

Jeff Young

Treat yourself to a hardback copy of Jeff's latest brilliant book Wild Twin :

https://www.littletoller.co.uk/shop/books/little-toller/wild-twin-by-jeff-young/Jeff is the newly-awarded winner of the TLS Ackerley Prize 2025 for his memoirWild Twin :

https://www.jrackerley.com/the-ackerley-prize

Alice Boyd

Listen to Alice's music on Spotify :

https://open.spotify.com/artist/7nwmqkSphItNiC3Pa8So7r?si=aWhvYLAvRZucBlE2UjLfeQBandcamp :

https://aliceboyd.bandcamp.com/Visit her YouTube channel to see more about her field recordings :

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCqOABIB9k2f2IeVHOuOvXAAVisit Alice's website :

https://www.aliceboyd.info/

Angie Woolf

Say Hi to Ange here :

https://www.facebook.com/Awordslingingwoolf/

Professor Yaffle

Listen to Professor Yaffle's brand new single - out today :

https://ditto.fm/everyone-wants-to-dreamPre-Order Professor Yaffle's latest album Everyone Wants To Dream, out in September :

https://www.violetterecords.com/store/p/professor-yaffle-everyone-wants-to-dream

La Violette Società 57

Buy a ticket :

https://www.violetterecords.com/tickets

Sharp Pins

Listen to Radio DDR :

https://open.spotify.com/album/2rMHZAlbmZuIsr8iWR7oZX?si=izRTjJLWS3SAfI-rSXfSKwVisit their Bandcamp :

https://sharppins.bandcamp.com/music

Violette Records

Keep us solvent :

https://www.violetterecords.com/store

Science & Magic

Back issues :

https://www.violetterecords.com/science-and-magic

These Buildings Are Tape Recorders, Unspooling Sound Archives of the City Remembering Itself

Listen on Spotify :

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/7E0lTvXRWe7SUxn6NC9KXv?si=8fcbda6c88a04b5